BREAKING: INVESTIGATION FINDS TESLA SUPPLIER ARCADIUM LITHIUM ($ALTM) DRAINING ARGENTINA'S ANDES OF WATER; FORENSIC ACCOUNTANT FINDS RED FLAGS IN FINANCIALS

In the high plains of the Andes in northern Argentina, a lithium company has been draining the region of its water since 1994. Amid a lithium boom in the global economy, Arcadium Lithium intends to get much larger – and use more water. All the while, the company’s flagship facility appears to have been more water intensive than the Arcadium has reported, according to Hunterbrook Media’s investigation. The side-by-side above reflects an area of the Andes outside of Arcadium’s development footprint (left), compared to a part of the region that is next to the facility (right). Images taken by Hunterbrook Media on January 31 and February 1 respectively.

Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is short Arcadium ($ALTM), long Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile (NYSE: $SQM), and long Albemarle (NYSE: $ALB). A member of the team submitted a whistleblower report regarding the company’s accounting to the SEC. Hunterbrook Media also shared key data with a shareholder litigation firm.

Authors: Daniel Sherwood, Katie Ross, Nick Gibbons

Editor: Jim Impoco

Hunterbrook Media just completed one of its most important investigations, a more than six-month dive into Arcadium Lithium, a key Tesla supplier created by the merger between Livent and Allkem. Read the full two-part story here and here.

The investigation involved scrutinizing tens of thousands of pages of permitting records, technical reports, court filings, scientific studies, and security filings — and led reporter Daniel Sherwood to the Salar del Hombre Muerto in Argentina, a 400-mile journey from the nearest airport.

The key takeaways:

Environmental: Arcadium has been consuming significantly more water than competitors, both in volume and relative to its production — creating local resistance and legal obstacles for the company. Our data analysis (methodology linked here) indicates the company has obfuscated the extent of its true water usage in Argentina.

Financial: Arcadium’s accounting raises red flags. While the merger between Allekm and Livent was expected to enhance market position and profitability, a closer look at Arcadium’s financial statements reveals several concerning irregularities that may raise questions about the company's long-term viability and the sustainability of its reported profitability.

In January, after months of researching Arcadium, Sherwood arrived in the Salar del Hombre Muerto — greeted along his route by graffiti demanding: “Miners leave.”

For years, Arcadium Lithium’s enormous water draw has depleted dwindling supplies for communities in Argentina and their revered ecosystems.

From Alfredo Morales, a resident of Antofagasta de la Sierra: “The human being is worth more than the electric car … The electric car is for those who have money, not us who are taking care of sheep here."

But while community members had reported damage, until now, the true extent of Arcadium’s water use had not been known.

What we found: Arcadium’s flagship operation has required more water to make its product than the company has presented — and more water than its competitors:

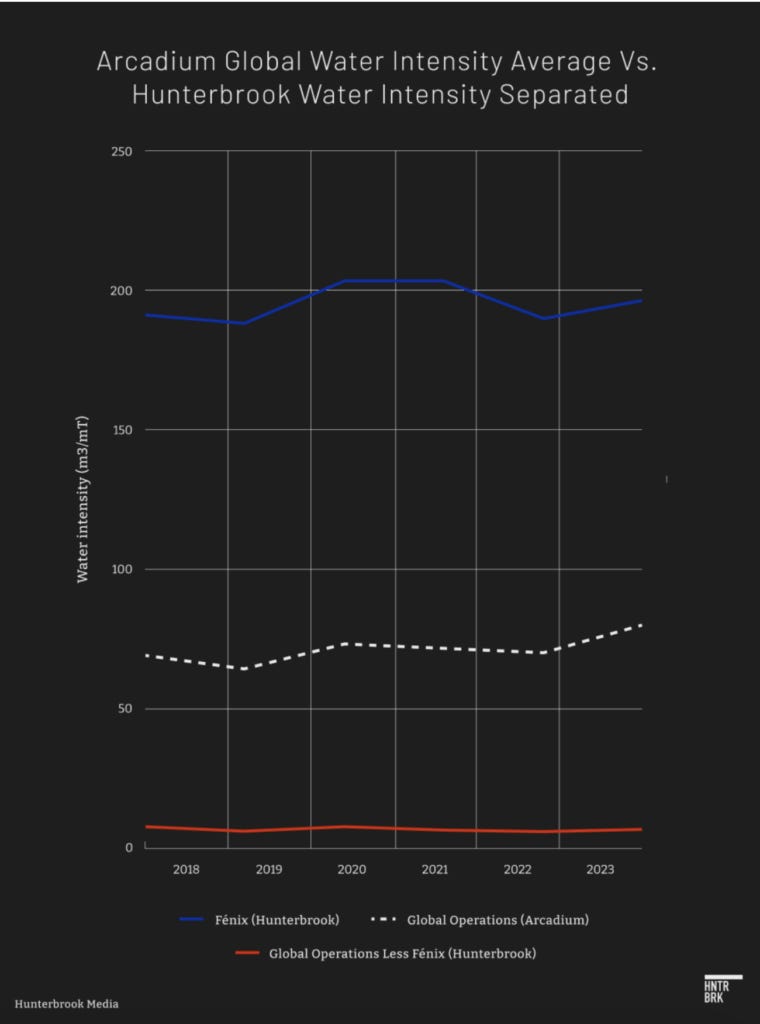

This graph reflects the water intensity Arcadium reported from 2018 to 2023 for its global operations against Hunterbrook Media’s estimated water intensity for Arcadium’s production during that period separated into the product Arcadium manufactures at Fénix — lithium carbonate — versus the other products Arcadium manufactures (lithium chloride, butyllithium, lithium metal, and lithium hydroxide) throughout the rest of its global footprint.

This graph represents Arcadium’s operating brine evaporation facilities in Argentina compared to its peers, Albemarle Corp. (NYSE: $ALB) and Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile S.A. (NYSE: $SQM), and their producing sites in Chile. Arcadium confirmed with Hunterbrook Media that it has not yet reported 2023 water consumption or intensity data. Hunterbrook modeled 2023 estimates based on Arcadium’s lithium production and input from the company — reflected by the dashed border in the respective bars above.

Suspecting that Arcadium's potentially misleading reporting might extend beyond its water usage, we brought in Nick Gibbons to conduct a thorough forensic accounting analysis.

Gibbons is a Certified Fraud Examiner and an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Accounting at NYU Stern School of Business. He’s worked at Two Sigma, Norges Bank Investment Management, and Citadel. He began his career in forensic accounting at independent equities research provider Gradient Analytics, where he exposed multi-billion dollar frauds.

Nick's findings raise serious concerns about Arcadium's financial practices:

Spring-loaded acquisition accounting: Arcadium's financial reporting following the merger with Allkem appears to mask a significant decline in Livent's profitability. As these merger-related benefits are exhausted over time, Arcadium's overall profitability is likely to meaningfully decline.

Excess liabilities and misclassified expenses: Arcadium's first-quarter earnings may be significantly overstated due to potential accounting irregularities and the misclassification of regular expenses as "transaction-related."

Disproportionate inventory levels: Arcadium's reported days sales in inventory (DSI) are significantly higher than its peers, suggesting potential accounting risks and future profitability compression.

Misleading financial targets: The company appears to have used misleading financial targets, such as adjusted EBITDA, to boost executive compensation. By including restructuring and merger-related charges in these adjustments, Arcadium may have met executive compensation thresholds it would have otherwise missed.

These findings — combined with Arcadium's seemingly deceptive water usage reporting — reveal a company that may be prioritizing short-term gains at the expense of long-term sustainability, transparency, and the well-being of the communities in which it operates.

The primary investigation was edited by Jim Impoco, the award-winning former Editor-in-Chief of Newsweek who returned the publication to print in 2014. Jim also served as Executive Editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune.

To read our full report on Arcadium's apparent exploitation of Argentina's water resources, click here. Please do. We’ve, uh, put a lot of time into this one — and the stakes are urgent.

Responding to an “old claim” from the community, the company began an irrigation and revegetation project in 2020, which remains ongoing.

Hunterbrook Media was unable to access the revegetation area when it visited the Salar in February, as security blocked the route and escorted our reporter to a different road. But satellite imagery we analyzed shows the area the company has targeted to restore accounts for less than 1% of the total damage.

In response to Hunterbrook Media’s questions about the company’s restoration efforts, Arcadium said: “The company continues its voluntary work to revitalize the area downstream from the small dam it built many years ago. This is a long-term undertaking.”

Arcadium’s dam, built in the 1990’s, has kept these wetlands dry and burnt. It took the company more than 20 years to begin addressing the damage. According to Hunterbrook Media’s analysis, the company has only brought 1% of the blackened area back to life.

For an in-depth look at Nick Gibbons' forensic accounting analysis, click here.

To examine our rigorous methodology and comprehensive data sources, click here.

— Hunterbrook Media

Excerpt:

THE COMPANY DRYING ARGENTINA’S ANDES TO POWER EVS

In the arid, high plains of northern Argentina’s delicate Salar del Hombre Muerto, a small river called Los Patos winds its way down the Andes to the basin floor. The river feeds a series of vegas, strips of green wetlands with a range of wildlife slivering between an otherwise rocky plateau.

Los Patos also feeds Arcadium Lithium PLC’s sprawling facility called Fénix, which sits on the edge of the salt flat in Catamarca. Arcadium is the largest lithium chemicals producer in Argentina and the fifth-largest in the world. It has made deals with Toyota, General Motors, BMW, and Tesla, among others.

The battery in electric cars — as well as smartphones, laptops, and even pacemakers — is made with lithium, a metal nicknamed “white gold” that is critical to meeting society’s goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The salt flats in Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia make up what the mining industry calls the “lithium triangle,” home to over half the world’s reserves.

The global lithium market has surged in the past two decades. Despite prices falling significantly, experts forecast more growth in the near future. The World Economic Forum estimates lithium “production needs to triple by 2025 and increase nearly six-fold by 2030” to meet demand.

But the extraction process is water-intensive, depleting the lifeblood of indigenous and local communities in the Salar del Hombre Muerto and elsewhere that far predate the approximately $25 billion lithium industry.

In recent months, Elon Musk, Tesla’s CEO, has spent significant time with Argentina’s president, Javier Milei. Lithium has been one of their main topics of conversation. Milei, meanwhile, has backed bills that would benefit Arcadium and other foreign miners of lithium.

But the lithium boom has already taken a heavy toll. Arcadium’s operations have played a role in draining the Trapiche River — a portion of which has dried up beneath a dam Arcadium built to pool and extract water for production at Fénix.

Arcadium says its recently completed aqueduct off the Los Patos river will reduce its reliance on the Trapiche. But the nearby indigenous Atacameño community and some members of the closest town, Antofagasta de la Sierra, maintain that the damage to the river is permanent. They fear Los Patos may face a similar fate.

On March 13, an Argentine court — citing damages to the Trapiche and pending lithium projects that rely on Los Patos — required the local Catamarcan government to assess how further development could affect the environment and neighboring communities.

While Arcadium acknowledges it operates in an area with a very limited water supply, a months-long Hunterbrook Media investigation found that the company consumes more water — by volume and relative to the amount of product it produces — than any of its Latin American competitors.

To analyze the water usage and production output of Arcadium and its rivals, Hunterbrook Media reviewed tens of thousands of pages of local permitting documents, mining technical reports, Argentinian court filings, peer-reviewed scientific studies, and security filings.

Our investigation showed that where other lithium companies have maintained or reduced their reliance on water in recent years, Arcadium’s water use has increased.

Hunterbrook Media also found that Arcadium has downplayed its water use by employing a methodology that differs from that of its peers — Albemarle Corp. and Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile S.A — which break out their water consumption on a per facility basis.

Arcadium also obfuscates the amount of water it consumes. It does so by averaging the lighter, more water-intensive lithium feedstock from Fénix with the heavier products that are produced outside of Catamarca, which use significantly less water — despite Fénix making up an estimated 95% or more of the company’s total water consumption. Read our full methodology here.

This graph reflects the water intensity Arcadium reported from 2018 to 2023 for its global operations against Hunterbrook Media’s estimated water intensity for Arcadium’s production during that period. The water intensity is separated into the product Arcadium manufactures at Fénix — lithium carbonate — versus the other products Arcadium manufactures (lithium chloride, butyllithium, lithium metal, and lithium hydroxide) throughout the rest of its global footprint. The graph was created by Hunterbrook Media.

Hunterbrook Media shared its data and calculations with Arcadium, which disputed our findings. In an email, a spokesperson said that the company “has never publicly disclosed information for individual sites (apart from its disclosures in product Life Cycle Assessments). Hunterbrook is therefore using global data in its calculations for Fenix.”

But based on the company’s lithium product volumes, water consumption data, and security disclosures, Argentine and U.S. state and federal permitting information, and an analysis of the company’s operational capacity, Hunterbrook Media determined that Fénix could account for nearly all of Arcadium’s global water consumption.

When pressed on this, Arcadium said: “We can state that the majority of Livent’s historical global water use can be attributed to Fénix, but if we are going to keep our responses specifically to what is in the public domain, we unfortunately cannot respond to your follow-ups with more specificity.”

Auto manufacturers that have deals with Arcadium — like BMW and Tesla — cite their interests in sustainable water use in mining and have visited salt flats in Chile and Argentina to underscore that point.

BMW, Tesla, General Motors, and Toyota all did not respond to Hunterbrook Media’s questions around their engagement with suppliers in regard to sustainability practices.

Hunterbrook Media asked Arcadium how it plans to fulfill its stated goals to reduce water intensity while also adhering to its aggressive growth plans. “While we expect to extract more water as we expand our operations and produce more volumes,” the company said in an emailed response to Hunterbrook Media, “we remain committed to sustainable water management across our operations and to reducing water intensity over time.”

In security filings, however, Arcadium stated, “There can be no assurance that we will have access to sufficient quantities of water to support our production operations, either at current capacities or our planned production expansion, in the future.”

For people like Claudia Santos, a weaver and a leader of a nearby Antiofaco community, the question of sustainability is not about business.

“Because of the cursed mining companies, it’s gotten worse because there’s no water,” Santos tearfully told a TV reporter in a June 2023 broadcast covering the rise of lithium mining in the region. “There’s no water to irrigate the alfalfa, there’s no water to irrigate the meadows.”

Arcadium’s plans are in limbo

Hunterbrook Media visited the Atacama Puna in February to better understand Arcadium’s operations.

After a 400-mile trek from the nearest airport and with 20 gallons of gasoline in the trunk, our reporter made it to the town closest to the site, greeted by signs directing mining traffic — and cold shoulders from the few people in the streets, several of whom were in Arcadium trucks or wearing mining hats.

As far as a six-hour drive from the center of Arcadium’s operations, graffiti demanding miners leave and keep their hands off Los Patos was peppered between signs advertising government development projects funded, in part, by Arcadium’s royalty payments.

Arcadium’s Fénix facility is a cornerstone of its operations, with plans to increase annual production to 100,000 metric tons of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) by 2030 — more than four times its annual production in 2023.

On the other side of the 230-square-mile Salar, roughly the size of the city of San Francisco, Arcadium is also building out another facility named Sal de Vida. The company plans to complete the first phase of Sal de Vida by the end of 2026.

Sal de Vida, which like Fénix draws from Los Patos, has been increasing its water extraction in the last two years as construction has advanced. But the March 13 court decision may temper Arcadium’s full growth prospects at Sal de Vida and Fénix, as the Catamarcan government completes its court-mandated analysis of the impact of its operations on the local water supply.

The Catamarcan agencies tasked with the analysis did not return Hunterbrook Media’s requests for comment.

While the exact timeline for the government’s review is unknown, corporate and environmental attorneys told Hunterbrook Media that it will likely be a lengthy process that needs to take into account the ever-changing status of projects, pressures of climate change, and technical specifics of the mine.

Argentina operations at center of Arcadium business model

Livent and Allkem merged on January 4, forming the world’s fifth-largest producer of lithium with an eye to becoming No. 3 in just a few years.

Livent traces its roots to Lithium Corp. of America, which was a supplier for the U.S. government’s thermonuclear bombs tested at the Bikini Atoll in the mid-1950s. By the early to mid-2000s, Livent was one of the three members of the lithium “oligarchy,” as its former VP and General Manager of the Lithium Division Jon Evans described it in the 2024 book The War Below. During that era and leading up to the merger, Livent’s only lithium extraction facility was Fénix.

Allkem’s operations came online more recently. Its mine in Western Australia started producing lithium in 2009. Allkem’s second active site is an evaporation facility in Jujuy, Argentina, north of the Salar del Hombre Muerto, built jointly with Toyota and backed by the Japanese government.

During the seven months it took the two companies to finalize the merger, an oversupplied market and a slowdown in electric vehicle sales sparked a rout in lithium prices, which have yet to rebound.

Arcadium’s market cap has lost more than 45% of its value since debuting on the New York Stock Exchange in January, according to the company’s share price as of market close on June 13. The company’s current value of around $3.9 billion is priced at around a third the combined value of Allkem and Livent at the time the deal was announced.

A separate Hunterbrook Media investigation revealed significantly misleading accounting practices related to the merger. The company did not provide comment on the findings of that investigation.

Given the slump in prices, Arcadium now cites diversification as one of the “merits of the transaction.”

The company’s footprint is indeed larger than ever, with lithium mining and processing facilities in Australia, Canada, the U.K., Japan, China, and the U.S., where the company maintains its corporate office.

But Arcadium’s operations still rely principally on its Argentinian ponds, which sourced 52% of its output and 68% of its revenues in 2023.

Arcadium notes the importance of Argentina to its business model and highlights that access to freshwater is “essential” to its operations there. The company also acknowledges that climate change and the shifting legal framework in the locations where it operates could limit its access to water even more and increase costs.

“Induced changes in natural resources from climate change could increase the risk of disruptions in production capacity,” Arcadium wrote in 2018 disclosures around climate change, continuing that the company “could experience increased costs in sourcing its raw materials as we take steps to mitigate this risk.”

Community members wait for Arcadium to address the dead wetlands that used to support their livestock herds

Arcadium has relied on water from the Trapiche since the facility’s initial development began three decades ago, damming the river and installing a network of groundwater pumping wells to “increase freshwater extraction rates,” according to a 2023 technical report.

Arcadium uses water from the Trapiche and Los Patos to process the lithium it pumps from deep beneath the salt flat into ponds, where the brine evaporates in the sun, leaving behind a higher lithium concentrate.

As early as 2000, the company observed the loss of vegetation in 32 hectares of the Vega Trapiche, wetlands that were fed by the river before the dam was built, according to a 2022 journal article in Wetlands and Ecology Management that cited environmental audits conducted by the company. Hunterbrook Media was unable to obtain the original documentation from the authors of the article and the respective Argentinian agencies.

Ranchers like the Condorí family, members of the Atacameños del Altiplano community who live and raise livestock near the Trapiche River, have long complained about the company’s operations. They say the mining companies have depleted drinking water stocks, disturbed herding habits, and threatened their way of life, and that the encroachment on their land has continued, according to numerous interviews in reports and documentaries by local human rights and environmental organizations and government bodies.

In an August 2022 video, a member of the family, Camilo Condorí, told local environmental education nonprofit Fundación Tantí, “It used to be beautiful, green, but before the company arrived you could raise anything. All of this green, but not anymore. What are [the animals] going to eat if everything is dry?” he asked, standing in front of the dried out portion of the Vega Trapiche that abuts one of his family’s homes.

Responding to an “old claim” from the community, the company began an irrigation and revegetation project in 2020, which remains ongoing.

Hunterbrook Media was unable to access the revegetation area when it visited the Salar in February, as security blocked the route and escorted our reporter to a different road. But satellite imagery we analyzed shows the area the company has targeted to restore accounts for less than 1% of the total damage.

In response to Hunterbrook Media’s questions about the company’s restoration efforts, Arcadium said: “The company continues its voluntary work to revitalize the area downstream from the small dam it built many years ago. This is a long-term undertaking.”

Google Earth satellite imagery recorded on June 13, 2024, from 30km scale narrowing in on the re-vegetation plot. Arcadium’s dam, built in the 1990’s, has kept these wetlands dry and burnt. It took the company more than 20 years to address the damage. According to Hunterbrook Media’s analysis, the company has only brought 1% of the blackened area back to life.

The slow-moving revegetation project was announced less than one year after Arcadium obtained its first permit to extract water from Los Patos in 2019. Now, the company has access to nearly 100% of the region’s supply of surface water.

Arcadium’s increasing appetite for water

The Salar del Hombre Muerto, which means “The Dead Man’s Salt Flat,” is named after a grave site that sits in a wetland fed by Los Patos, one of a number of cultural sites throughout the region that marks the generations of families that have lived in the area for more than 2,000 years.

With its unique combination of remoteness, past volcanic activity, and high elevation, the area is host to a high degree of biodiversity — from threatened and endangered flamingos, reptiles, fish, and small and large mammals to rare microorganisms that scientists study to learn about early Earth.

A short distance to the south is Laguna Blanca, a UNESCO conservation site created in 1979 to prevent the area’s dwindling population of wild llamas from going extinct. Protections were strengthened in the following years to preserve archaeological sites and restrict development.

When Hunterbrook Media visited the area, the wide valleys walled in by towering mountains on either side lead up to the salt pan. The otherwise surreal soundscape of the whipping wind, occasional bleat of a llama, and distant babble of water was interrupted by the rumble of trucks, utility vans, and security vehicles that were swarming the Salar.

The service roads that connect one lithium site to another are punctuated by ribbons of Los Patos that have disappeared into the crusty soil, dotted by dried bushes or the occasional sand dune that make the small areas of green vegetation stand out that much more.

As Arcadium’s plans to rely on Los Patos became more widely known, environmentalists and community members increased their calls for government intervention.

“They are now asking to extract fresh water from the Los Patos River, which is the main river in the Catamarca highlands, the most beautiful in the world,” Patricia Marconi, president of the cultural preservation nonprofit YUCHAN Foundation, said at a 2023 energy transition conference.

She said Arcadium’s Fénix project consumes “78 times more than the fresh water consumed by Antofagasta de la Sierra,” referring to the local community. She added that the company had done “irrecoverable” damage to the Trapiche River.

“These environments will disappear, and all the ecosystem goods and services they provide will disappear,” Marconi said.

By late 2023, it was estimated that 25% less water was flowing into Trapiche’s aquifer compared to 1994, the year Arcadium dammed the Trapiche River.

“The human being is worth more than the electric car,” Alfredo Morales, a resident of Antofagasta de la Sierra, the closest town to the facility, told cable news DW Español in a December 2023 broadcast on lithium extraction and the Trapiche. “The electric car is for those who have money, not us who are taking care of sheep here.”

Water extraction and community resistance

Although Milei, Argentina’s new libertarian leader, has indicated he would like to cut costs for miners in his country, his plans are still in early stages.

In the meantime, the local court that oversees mining in Catamarca is shifting in another direction. In March, a provincial court ruled that the Catamarcan government must consider how the proposed development in the Salar del Hombre Muerto would impact the Los Patos river and living conditions for local communities.

The lawsuit was filed in 2021 by Román Elías Guitián, the leader of the Altiplano Atacameños Community who is part of the third generation of his family to be raised in the Salar. Like others, he resents the lack of engagement from the companies whose operations he says have threatened his family’s livelihood.

“We are not against progress; we just want things to be done correctly because this way, they are destroying us,” Guitián told Infobae, a global digital media outlet with a focus on Argentina. “They never presented the environmental impact studies, they didn’t listen to our concerns, nor did they respect the processes of prior, free, and informed consultation, as required by law.”

The Catamarca Prosecutor’s Office filed an appeal a month after the resolution order, according to the local daily newspaper El Ancasti. The court has yet to respond. The Catamarcan government said it needs to complete the study before it can issue further mining permits and authorizations related to extracting water from Los Patos but that any permit already issued is valid.

Vania Albarracín Silva, Ecosystems Program attorney at the legal nonprofit Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense, told Hunterbrook Media: “While the goal is to ensure a stable operating environment for mining companies, these processes tend to be lengthy due to their rigorous nature and the need to comply with international standards and best practices that prioritize responsibility to local communities and human rights.”

In a press release, Arcadium said the court’s ruling “does not impact Arcadium Lithium’s existing mining operations and expansion activities.”

At the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense, one of the groups working with community members in the Salar del Hombre Muerto, attorney José David Castilla predicted more lawsuits down the road.

“In a context related to the climate crisis and the gradual increase of human rights issues, it is possible that more communities will be suing around the concept of access to water as a specific human right,” he told Hunterbrook Media.

“A specific example of this situation is the Puna and the Atacama Desert. According to our analysis, we show that there is a trend of increasing risks related to access to water that endanger communities and ecosystems. Countries in these regions need to strengthen their environmental regulations to properly apply the precautionary principle and ensure access to water and climate adaptation for the survival of communities and their territories.”

Arcadium competes for finite amount of water

Less developed than Chile’s adjacent lithium industry, Argentina has seen a rush of foreign prospectors eager to profit off its reserves. Over the past 30 years, the number of lithium mining projects located in the Argentine High Andean Plateau has increased from one to more than 100, according to Hunterbrook Media’s database of Latin American lithium permitting and exploration records.

In Argentina, the growing industry is especially concentrated in the Salar del Hombre Muerto basin, with companies trying to advance at least seven active mining projects.

Each mining company requires water access for its activities. Arcadium flags that this increase in development could lead to “long term deleterious effects on production” or its ability to access the water in the first place.

Juan Sonoda, managing partner and head of the Litigation and Energy & Natural Resources departments at the Argentinian corporate law firm Beretta Godoy, told Hunterbrook Media that new projects can adversely impact others that are already permitted or even operating.

“As each project reaches its feasibility stage,” Sonoda explained, “its environmental impact assessment for development and production should reasonably consider the current conditions and the interactions with existing projects, which are likely to become more sophisticated with the emergence of new projects. This may also apply to the environmental impact assessment of the existing projects, which must be updated every two years.”

More water for Arcadium or any other operator means less for Román Elías Guitián, the Altiplano Atacameños Community leader whose lawsuit led to the March ruling.

Argentina is home to almost 14,000 Atacameño people like him. Their ancestors survived centuries in one of the world’s driest areas through waves of Inca and Spanish conquest. Now, the Atacameños people are fending off a global lithium grab.

“My whole family lives off livestock farming, and this situation affects our lambs, our llamas,” Guitián said. “They asked me to support the mining ventures … I tell the brothers of other communities that we only seek for things to be done right, for them not to destroy us.”