Hims & Hers Selling GLP-1 Injection That's Not FDA Approved, From Shady Supplier — And Won't Make You Talk to a Doctor to Get It

Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is short $HIMS.

By: Sam Koppelman, Michelle Cera, Matthew Termine

Editor: Jim Impoco

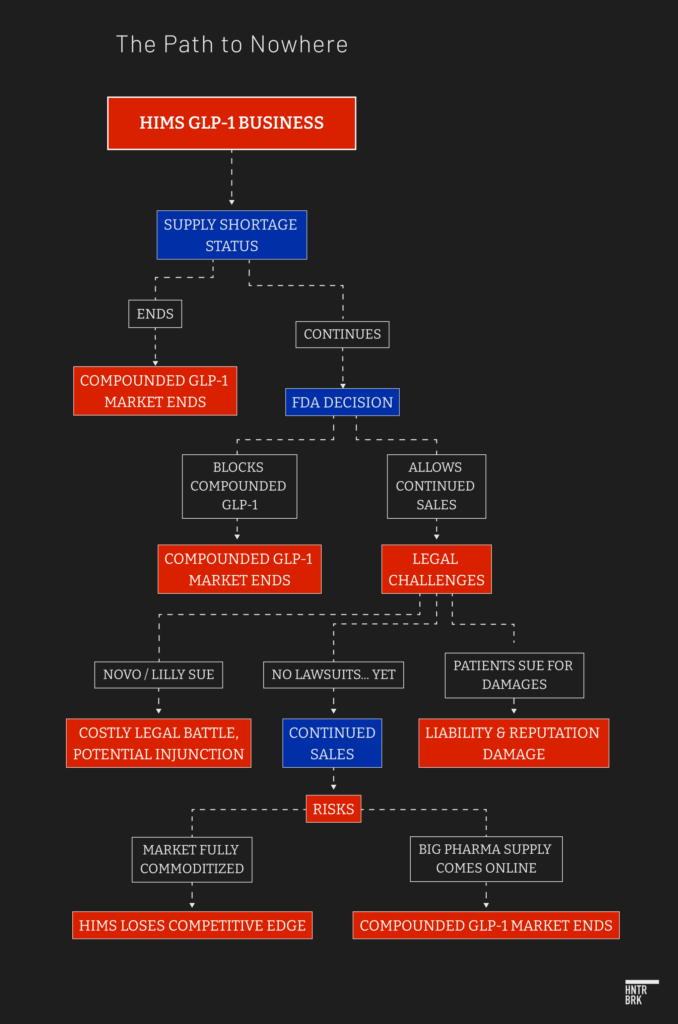

Hims & Hers sells knockoff GLP-1 weight loss drugs through a loophole that could end at any time.

Hims relies on a sole GLP-1 supplier with previously unreported ties to fraud and bankruptcy.

An obesity doctor called GLP-1 knockoffs “the largest uncontrolled, unconsented human experiment of our lifetime.”

A Hunterbrook Media reporter qualified for GLP-1 knockoffs from Hims after a 4-minute survey — then got a prescription without speaking to a doctor or submitting medical records.

Hims could suffer legal liability if GLP-1 knockoffs prove unsafe, ineffective, or violate a Big Pharma patent — according to an FDA legal expert.

GLP-1 drugmakers are litigating against unapproved knockoffs like those sold by Hims. Experts say Hims could be subjected to a patent suit regardless of the loophole it’s using.

Hims executives, including the Chief Executive Officer and Chief Legal Officer, have sold more than 1.7 million shares, realizing $26.4 million of net proceeds since their announcement on May 20 that Hims will sell GLP-1 knockoffs.

Belcher, Hims’ supplier, told Hunterbrook Media it is “manufacturing the compounded GLP-1 as a drug shortage product to service a community need” and “complying with all necessary parameters as they pertain to safety.” Hims did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

“I … felt like death in bed,” recounts a Reddit user, describing their harrowing experience with a knockoff GLP-1 weight loss drug. “I was … too nauseous to even drive or walk to the mailbox.” Another patient accidentally doubled their dosage, leading to days of misery: “Honestly, this was the worst experience ever, and I hope no one else has to go through that.”

These two alleged patients — both of whom exchanged messages with Hunterbrook Media — appear to be part of what Dr. Angela Fitch, former director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Weight Center, has called “the largest uncontrolled, unconsented human experiment of our lifetime.”

Both Reddit posters claim they had ordered the medication from Hims & Hers Health Inc. (NYSE: $HIMS), a telehealth company whose stock price at one point soared more than 60% since announcing it entered the booming market for these controversial drugs.

Unlike the name-brand GLP-1 drugs Ozempic and Wegovy sold by Big Pharma, Hims sells injections that have not been FDA approved. The company is doing so through an FDA loophole that enables facilities called compounding pharmacies to sell their own versions of patented drugs during shortages.

But a Hunterbrook Media investigation reveals that the compounder Hims has partnered with to manufacture these drugs — BPI Labs LLC — is wholly owned by Belcher Pharmaceuticals LLC, a business with a history of FDA scrutiny and former executives convicted of fraud.

In one case, two executives from Belcher were convicted and sentenced to prison time in what the Department of Justice called a “Nationwide Telemedicine Pharmacy Health Care Fraud Conspiracy.”

The GLP-1 drugs that Hims sells are produced by a Belcher-owned subsidiary — and Hims does not appear to be prescribing through a particularly rigorous process, according to conversations with multiple patients.

A Hunterbrook Media reporter qualified as eligible for GLP-1 drugs with Hims after completing a four-minute survey and received a prescription under an hour after submitting it, without speaking to a doctor or submitting medical records.

An FDA legal expert told Hunterbrook Media that Hims may have opened itself up to liability with its compounding business — risking litigation from Big Pharma and regulatory intervention from the federal government. The company is also risking the health of its patients, according to multiple obesity doctors who spoke with Hunterbrook.

Dr. Rajesh Aggarwal, an obesity doctor and founding CEO of twenty30 health — a technology platform for individuals with obesity and metabolic disease — described the world of GLP-1 compounding as a “Wild West preying on desperate individuals.”

Dr. Fitch shared a similar sentiment. “This is a marginalized group of people you’re taking advantage of,” the past president of the Obesity Medicine Association, who is currently the chief medical officer of an obesity medicine clinic, told Hunterbrook Media, referring to the stigma that people with obesity face.

“And our society is allowing people with obesity to take a product that might be inferior or ineffective, because there’s such a bias against obesity that people are like: ‘They did it to themselves … If they die, they die.’”

Hims did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

BACKGROUND: HIMS ENTERS THE KNOCKOFF GLP-1 MARKET

Hims launched in 2017 selling generic versions of Viagra and hair loss treatments online.

Since going public in 2021 through a $1.6 billion SPAC deal, it’s grown into a major telehealth company, expanding into mental health and dermatology — although Hims continues to post videos about, well:

On May 20, Hims announced it would also sell its own version of GLP-1 weight loss injections like Ozempic and Wegovy.

These injectable medications, which help patients shed body weight by suppressing appetite, have been labeled a medical miracle — and created a market potentially worth hundreds of billions of dollars. Novo Nordisk, which owns the patent for Ozempic, now has a market cap bigger than its home country Denmark’s gross domestic product.

But the marketplace for these medications has gone haywire. Counterfeit GLP-1 drugs have become, as Katherine Eban wrote in a Vanity Fair investigation, “a hot commodity among transnational crime groups, homegrown counterfeiters, rogue compounders, shady middlemen, unscrupulous doctors, and medi-spas of dubious legality.”

By February, Eban reported, “illegal pharmacies in the US were filling more than 734,000 GLP-1 prescriptions per month,” according to data compiled by Translucent DataLab, which scrutinizes illegal online pharmacies, and IQVIA, a major data and clinical research company.

As the supply shortfall has driven explosive growth in the black market for GLP-1 drugs, the FDA has temporarily allowed production of what are known as compounded versions of the drugs. These versions, unlike generics, are not FDA-approved. The loophole is Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which enables compounding facilities to produce knockoff versions of drugs that are in shortage.

This was the opening Hims needed. Partnering with BPI, Hims is offering a compounded version of semaglutide (the key ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy) for as little as $199 per month out of pocket. Hims doesn’t accept insurance, but that is still a fraction of the cost many Americans are paying for the brand drugs, which can run up to $1,400 a month, as reported by The New York Times.

Insurance can reduce the price of the patented GLP-1 drugs to $25 a month — but patients often struggle to gain coverage for the drugs through their plans, as many insurance companies have stopped covering these medications.

Logan, a 28-year-old teacher from Iowa, told Hunterbrook Media he had been denied access to GLP-1 drugs by insurance four times — even though he had been prescribed Wegovy by a doctor. That is how he ended up purchasing the compounded version through Hims.

BPI LABS: THE HIMS SUPPLIER’S SHADY HISTORY

The company that makes GLP-1 knockoffs for Hims is BPI, a wholly owned subsidiary of Florida-based Belcher Pharmaceuticals.

In 2020, two Belcher executives were convicted in a massive medical fraud scheme that ranged from paying kickbacks to physicians to repackaging over-the-counter medicines and vitamins as prescription-only drugs to boost pricing.

One of these convicted fraudsters, Mihir Taneja, pleaded guilty on November 30, 2020, to “introduction of misbranded drugs into interstate commerce with the intent to defraud and mislead.” He was sentenced to 10 months in prison followed by one year of supervised release and was ordered to pay almost $21 million.

According to the Department of Justice, Taneja and Arun Kapoor, formerly Belcher’s Director of Business Development, had founded a sham pharmacy called Sterling-Knight for their scheme.

“Neither BPI nor Belcher have any history of criminal convictions,” a spokesperson told Hunterbrook Media in a written statement. “The primary allegation against Belcher … was wrongful discharge based on matter [sic] unrelated to Belcher and issues related to Mihir Taneja were unrelated to Belcher/BPI. Additionally, Mihir Taneja has not been associated with Belcher/BPI as an employee, owner or officer for over five years.”

Before his sentencing, Taneja was the CEO of a health care firm called GeoPharma Inc., which traded under the ticker GORX and was then the parent company of Belcher.

GeoPharma gained notoriety in 2004 when it issued a press release misleadingly claiming FDA approval for a new “prescription product” to treat the side effects of chemotherapy and radiation. The stock shot up, likely because the public assumed this new product was a drug. But it turned out the product was not a drug at all, but rather only FDA-approved as a medical device.

GeoPharma went bankrupt in 2011. Shareholders then sued alleging that, prior to the bankruptcy, the Tanejas had sold Belcher at a suspiciously low valuation to a shell company owned and controlled by the Tanejas themselves. The company was subsequently sued by the U.S. Department of Labor for allegedly mismanaging retirement funds, which resulted in consent orders against two former GeoPharma executives, the CFO and Controller and Director of Human Resources.

Belcher has since been accused of engaging in widespread fraud by former Chief Science Officer Darren Rubin, in a whistleblower suit filed in 2020.

In the suit, Rubin accused Belcher and members of the Taneja family of engaging in a wide-ranging scheme to defraud Medicare and the military’s TRICARE. A similar case was brought by the United States, on behalf of the Department of Defense, against Mihir Taneja — alleging over 4,000 fraudulent claims to TRICARE, totaling approximately $19 million in payments. Taneja denied these claims but the parties appear to be headed towards a settlement.

BPI has faced scrutiny from the FDA as well.

In 2021, BPI was served with a “Form 483” letter from the FDA, alleging the company was using improper equipment and procedures and failing to vet suppliers adequately.

In its response to Hunterbrook Media’s request for comment, BPI clarified: “The audit was successfully closed, and the FDA issued an Establishment Inspection Report (EIR) confirming satisfactory compliance. Subsequently, the BPI product received final FDA approval.”

The company also noted that “neither Belcher nor BPI have ever had Warning Letters issued to them” from the FDA.

BPI has since opened several new facilities highlighted in Rubin’s lawsuit. One stands out. “BPI Labs is launching a number of 503B injectable products,” the lawsuit warned, claiming the facility was built to produce “large batches with or without prescriptions.”

The case settled on May 21, according to PACER.

That same month, Hims announced it would partner with BPI on its GLP-1 drugs, producing the injectables at the very 503B facility that Rubin mentioned in the lawsuit.

“Settlements, as I am sure you know, do not admit liability,” Belcher told Hunterbrook Media. “Additionally, the government did not intervene in the action.”

BPI also told Hunterbrook Media that it is a “FDA registered complex generic and NDA drug manufacturer and as such all our operations are conducted under the strict standards required by those regulations,” including the “Current Good Manufacturing Practice—Guidance for Human Drug Compounding Outsourcing Facilities Under Section 503B of the FD&C Act.”

Compounding pharmacies have for decades provided additional supply in shortage and customized dosages that are not available from other manufacturers. But injectables from some compounding pharmacies have proven deadly.

Injectables, unlike oral treatments, bypass the body’s defenses that guard against pathogens entering the bloodstream and are required to be produced in sterile conditions. In 2012, the New England Compounding Center failed to maintain a sterile manufacturing facility. Fungal meningitis infected hundreds of people and killed at least 64.

HIMS PRESCRIBES KNOCKOFF GLP-1 DRUGS ONLINE WITHIN MINUTES — WITHOUT A DOCTOR CONSULTATION

Hims may not be a household name, but on social media, it’s pretty close to one. And posts from patients about the company’s GLP-1 drugs — which were advertised during the NBA Finals — raise red flags.

On Reddit, for example, customers have reported that they did not have to consult with a doctor before being shipped the drug.

A Hunterbrook Media reporter was able to order the drug from Hims in a matter of minutes after filling out a survey — without speaking to a doctor, sharing any of her medical records, or conducting blood testing.

The first step was a survey that took four minutes to complete. The survey asked about weight, mental health history, and weight loss goals. There was an option to upload blood work but it was not required.

The end of the survey suggested a treatment plan and offered a choice between 3-, 6-, and 12-month supplies. About 20 minutes after the survey was submitted, Hims offered a prescription via text, and compounded semaglutide was on the way.

The only “consultation” with a health care provider was what appeared to be an automated message in a chat-box about how to inject.

SAFETY AND EFFICACY CONCERNS RAISED BY THE FDA, AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT, AND BIG PHARMA — AFTER FIVE DIE ON COMPOUNDED GLP-1 DRUGS, AND OTHERS REPORT SERIOUS SIDE EFFECTS

Despite allowing compounding, the FDA has expressed concerns about GLP-1 knockoffs. In April, the agency warned that some compounded semaglutide products contain salts and impurities, unlike the approved formulations, and may be less safe and effective.

Scott Gottlieb, the FDA’s former commissioner, said on CNBC that many of the compounds “won’t deliver the expected benefit.”

The agency’s safety concerns appear to be well founded: between February 2019 and December 2023, the FDA received 352 adverse event reports related to compounded GLP-1 drugs, including five deaths. And last year alone, “poison centers reported nearly 3,000 calls involving semaglutide, a more than 15-fold increase since 2019,” according to the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy.

Like the FDA, Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration responded to the shortage by opening the door to knockoffs. But on May 22, after reports of side effects, the nation’s health minister announced the government would ban the production of compounded GLP-1 drugs.

“Those exemptions have never allowed the sort of large-scale manufacturing that we’re seeing in this market with products pretending to be Ozempic or Mounjaro,” said the health minister, who was also quoted as saying: “This action will protect Australians from harm and save lives.”

Dr. Aggarwal told Hunterbrook Media that these drugs can be transformational — and he understands the imperative of finding more affordable ways for them to reach patients. But he said he is also concerned about the fact that, for compounders, it’s “challenging to get the right ingredients.”

And, as a result, human beings are injecting themselves with versions of GLP-1 drugs “meant for laboratory studies,” which, Aggarwal said, “could be harmful.”

“At the end of the day, these are real humans we are taking care of,” he said. “The Hippocratic oath is: ‘First: Do no harm.’ And I am concerned people are getting harmed.”

HIMS SKIRTING THE LINE AS NOVO AND LILLY SUE COMPANIES SELLING COMPOUNDED GLP-1 DRUGS

Hims has entered the market at a time when companies selling knockoff GLP-1 drugs are facing mounting litigation from Big Pharma. While ramping up GLP-1 supplies to resolve the shortage, Lilly and Novo are aggressively suing sellers of compounded versions of their drugs.

In recent months, Novo has taken legal action against clinics, medical spas, and compounding pharmacies claiming to offer semaglutide — accusing them of “false advertising, trademark infringement and unlawful sales of non-FDA approved compounded products.”

Novo also claimed to have tested samples of the compounded GLP-1 drugs from these entities — and found that they had significant “impurities” and “do not have the same safety, quality and effectiveness assurances as FDA-approved drugs.”

Dr. Fitch had a similar experience — with a patient who ended up “throwing up for days” after taking a compounded GLP-1 drug. The formulation, Dr. Fitch said, was “clearly different” from the name brand version. (Dr. Fitch told Hunterbrook Media she has consulted with a wide range of clients in the past, including Lilly, Novo, Vivus, Rhythm, Currax, Jenny Craig, Seca, and Sidekick.)

In February, Novo announced settlements with two of the Florida defendants, which agreed to disclose that their compounded drugs have not been vetted by the FDA for safety and effectiveness.

Lilly followed up with lawsuits of its own on June 20 — aiming to combat “unsafe compounded products.”

So far, neither Novo nor Lilly appear to have sued Hims. But the company’s supplier, BPI, has a long history of litigation related to alleged patent infringements — from Endo International Plc, Viatris Inc., formerly known as Mylan (NASDAQ: $VTRS), Sanofi (NASDAQ: $SNY), and Novartis (NYSE: $NVS). Belcher denied these claims.

And Hims appears to be toeing the line. Unlike the clinics and medical spas targeted by Novo, Hims does reveal that the drugs it sells are not FDA approved — but in one ad seen by a Hunterbrook Media reporter, it does so only in barely visible font that blends into the background of its ads. (Try to read the disclosure below.)

And while Hims does not claim to be selling Ozempic, as some of the spas Novo sued allegedly did, the company does use the name Ozempic in its advertising.

Shashank Upadhye, a founding partner of Upadhye Tang LLP — an IP & FDA boutique law firm in Chicago — and author of “Generic Pharmaceutical Patent & FDA Law,” a textbook now in its 14th edition, served as chief in-house counsel at three leading pharmaceutical companies: Apotex, Inc., Sandoz-Novartis, and Eon Labs, Inc.

In an interview with Hunterbrook Media, Upadhye said that even with a green light from the FDA to sell compounded drugs, Hims could still face future patent litigation.

“Novo and Lilly have patents,” he explained. “And the question is when, if at all, they’re going to take them out and assert them against Hims.”

“Let’s just say a compounding pharmacy, a 503B pharmacy, makes a few dozen injections here or there. Is that worth it for Lilly and Novo to take their patents and sue in court? Maybe. Maybe not. But what happens if a few dozen injections become a few hundreds and a few hundreds become a few thousands?”

Ultimately, he said, it will come down to the following question: “At what point does a bug become a nuisance — and at what point does a nuisance become a danger?”

If Novo sues, Hims could face a preliminary injunction and be forced to stop selling the compounded drugs immediately, Upadhye explained.

And if a court declined a pretrial injunction — but later ruled in favor of Novo on the merits of the case — Hims could be mandated to pay damages on every injection of GLP-1 drugs it sold. Although, of course, Upadhye made clear, it’s hard to predict exactly what courts will do. Much will also depend on what patents are asserted against a 503B company.

Compounders also have exposure to personal injury litigation. If a patient were harmed by a compounded GLP-1 drug, “the lawyer would sue everyone.”

“They would sue Hims. They would sue the compounder. That’s a potential liability,” Upadhye explained.

FDA COULD CLOSE LOOPHOLE ALLOWING HIMS TO SELL GLP-1 KNOCKOFFS AT ANY TIME — AND EXPECTS SHORTAGES TO EASE AS EARLY AS NEXT WEEK

Compounding pharmacies face another existential threat: Once shortages ease, the FDA will close the loophole that allows compounding.

Within 60 days of an announcement that a shortage is over, compounders would no longer have a right to sell the drugs, said Upadhye. He added that if a company like Hims refused, it could face an enforcement action from the FDA or “a lawsuit on day 61.”

As of publication, the FDA lists the majority of doses for Novo’s semaglutide drug (Ozempic, Wegovy, or Rybelsus) as “available.” Eli Lilly’s tirzepatide (Mounjaro) is in “limited availability” across several doses.

According to the FDA, this limited availability will last through Q2 2024, the end of this week.

Some experts who spoke with Hunterbrook, including Dr. Fitch and Dr. Aggarwal, said that they believe the shortage could last significantly longer.

HIMS INSIDERS SELL MILLIONS WORTH OF SHARES — AS COMPOUNDED GLP-1 MARKET BECOMES COMMODITIZED

Even with the loophole still open, and safety issues aside, the stock gains of jumping on the GLP-1 bandwagon have proved ephemeral. While the stocks of producers of GLP-1 drugs, including Lilly and Novo, have soared, downstream players in the weight-loss space have quickly lost gains.

For instance, last year, the stock of Weight Watchers parent company WW International (NASDAQ: $WW) more than doubled after announcing a $100 million deal to acquire Sequence, a telehealth startup focused on helping patients access GLP-1 drugs. Analysts predicted the move would revive the struggling diet giant, but the stock has since plummeted more than 90% as the hype collapsed.

The problem is that the market has commoditized nearly as rapidly as it has grown. “With everyone online selling GLP-1s,” Spencer Nadolsky, the medical director at Weight Watchers, wrote on X earlier this year, “What will you do to be different?”

In another post, he wrote: “You’re going to have to come up with a different value proposition beyond access to these medicines.”

Hims executives appear to be cashing out while they can.

Since the company’s share price spiked on the announcement it would sell GLP-1 drugs, the chief executive officer, chief operating officer, chief financial officer, chief legal officer, and other executives have sold have sold more than 1.7 million shares, realizing $26.4 million of net proceeds since their announcement on May 20 that Hims will sell GLP-1 knockoffs.

The CFO, CLO, and CCO sold some of this stock by exercising options that didn’t expire until the 2030s as well as shares related to recently vested restricted stock units.

And rather than holding the stock for a year, which could have potentially unlocked a lower long-term capital gains tax rate, they sold right away.

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

Michelle Cera is a sociologist specializing in digital ethnography and pedagogy. She is a Ph.D. Candidate in Sociology from New York University, building on her Bachelor of Arts degree with Highest Honors from the University of California, Berkeley. Currently serving as a Workshop Coordinator at NYU’s Anthropology and Sociology Departments, Michelle fosters interdisciplinary collaboration and advances innovative research methodologies.

Matthew Termine is a lawyer with nearly five years of experience leading the legal team at a mortgage technology company. In 2017, Matt was credited by the Wall Street Journal, among others, for identifying suspicious mortgage loan transactions that led to several successful criminal prosecutions, including that of a prominent political operative and the chief executive officer of a federally chartered bank. He is a graduate of Trinity College and Fordham University School of Law. He grew up in Old Saybrook, Connecticut and now lives in Brooklyn with his wife and two sons.

Jim Impoco, who edited this article, is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek who returned the publication to print in 2014. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has a Master’s in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

Nick Gibbons, a Hunterbrook Media advisor, also contributed reporting. His experience includes a blend of qualitative and quantitative investment roles at Two Sigma, Norges Bank Investment Management, and Citadel. He began his career in forensic accounting at independent equities research provider Gradient Analytics. He is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Accounting at NYU Stern School of Business, a Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE), and Master Analyst in Financial Forensics (MAFF).

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work opportunities, and press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.