POSCO INTERNATIONAL: OPERATING A GAS PROJECT WITH MYANMAR’S SANCTIONED, MURDEROUS REGIME

Posco says its gas serves the people of Myanmar by fueling power plants to provide electricity. But a growing amount of gas appears set to imminently flow to junta steel mills.

An elementary school in Ann Thar village, Rakhine state, March 7, 2024, after it was shelled by the junta. The Junta’s attacks killed more than 800 children from the date of the coup, in February 2021, to the end of 2022, according to the U.N. The junta buys many of the weapons for these attacks with revenues from offshore gas projects. The Shwe gas project, operated by Posco International, is one of the biggest. Source: Citizen journalist via Radio Free Asia

By Jenny Ahn, Daniel Sherwood, and Blake Spendley

Hunterbrook Media’s investment affiliate, Hunterbrook Capital, did not take any positions related to this article. Read full disclosures and detailed footnotes on hntrbrk.com/posco.

At around 1:30 a.m. on March 15, a Myanmar military jet dropped two bombs on a small village in the northwestern state of Rakhine. Most villagers were asleep. The bombs killed 21 of them instantly and injured 30 more. The village, Thar Dar, had become a refuge for people fleeing Sin Gui Pyin, a nearby community where the junta had recently slaughtered residents, according to Radio Free Asia.

“The junta is targeting these horrendous, brutal attacks at civilians,” said a Myanmar activist, who asked not to be named. “There is no strategic reason for the junta to bomb this village, other than to put fear on the people.”

The junta’s bombing of Thar Dar is part of intensifying airstrikes and other attacks against civilians in what the U.S. media views as the junta’s strategy to “punish” and “control and divide the population through fear and brutality.” Since last October, an aggressive campaign by armed resistance groups has put the junta increasingly on the defensive.

A major source of the money that the junta uses for jet fuel and weapons is Myanmar’s four offshore gas projects. Of those, the Shwe project, operated by Posco International Corp. in joint ownership with an entity controlled by the junta, has been the most profitable in recent years, according to a report by the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar. The report claims Shwe provided over a half billion dollars per year to the regime in the two years after the coup, helping fund a $1 billion spending spree for arms, including fighter jets, attack drones, assault helicopters, tank parts, and advanced missile systems.

The purchases have enabled what the U.N. Special Rapporteur called “probable crimes against humanity,” including murder, torture, sexual violence, and the pillaging of villages.

After the coup, major energy companies from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development member countries that were operating Myanmar’s offshore gas projects left, citing human rights violations. Not Posco.

Posco not only chose to stay, but continued to pour in hundreds of millions of dollars to increase production at the Shwe gas project, even as evidence of junta atrocities grew.

At the same time, Posco was marketing itself as a globally responsible, ESG-conscious company. It promised to address “social issues with empathy,” while abiding by the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Its institutional investors include funds with ESG commitments, like Vanguard and BlackRock, and the company has seen its stock soar alongside a promised transition to more renewable industries.

“The gas companies are actively contributing to human rights abuses,” said Ben Hardman, legal coordinator at EarthRights International, an environmental and human rights advocacy group. “At that level of funding, it’s not about, ‘How do we balance our obligations to shareholders?’ No, you must cease. It’s not optional. The U.N. Guiding Principles are very clear.”

Myanmar has become more closed off since the junta took power, and the scale and effect of Posco’s gas project have been unclear to outsiders. To fill crucial gaps in Posco’s disclosures, Hunterbrook Media gathered and analyzed historical field studies related to the gas project and pipeline, customs and investment data, and historical documents on Myanmar’s gas-fired capacity, generation, and distribution, as well as geospatial, social media, and other publicly available data.

Between Hunterbrook Media reaching out for comment and publication, Posco International’s website was updated — and the English version is no longer accessible. In these cases, hyperlinks have been removed.

Posco says that suspending Shwe would “reduce the nation’s power generation” and take “a heavy toll on the daily lives of Myanmar people.” But the majority of Shew gas is exported to China, and as of this year, more of the gas allocated for domestic use is set to flow — and may be already flowing — to regime-run steel mills with links to multiple sanctioned entities and the junta’s domestic weapons manufacturing apparatus. Meanwhile, homes and businesses across Myanmar have faced an increase in electricity shortages since the coup, amid a shutdown of nearly half of the gas-fired power plants fed by Shwe gas.

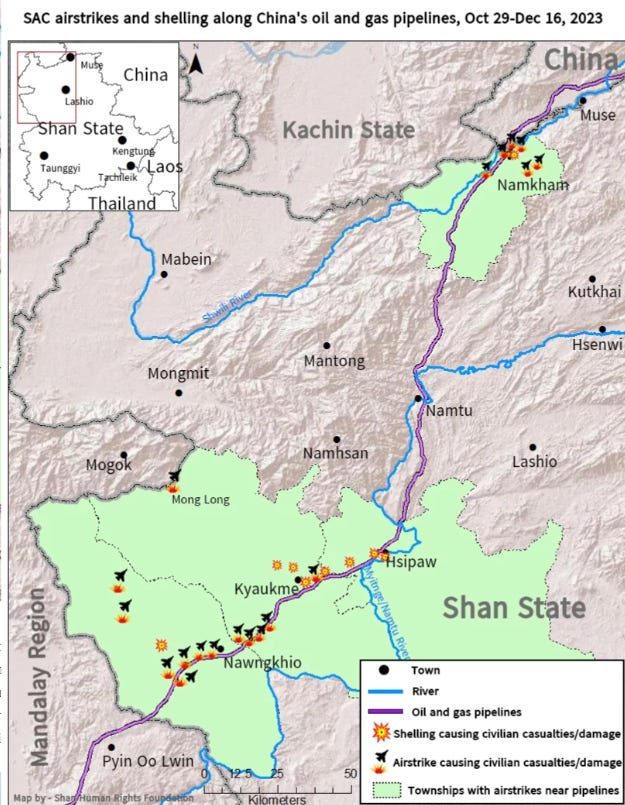

The Shwe project is also a growing business risk to Posco, given that all of the gas produced at Shwe is transported via a single pipeline that cuts through the scene of an intense civil war in northern Myanmar, where the junta is battling militant groups that oppose the regime. Since the fight heated up in October, villagers have fled some areas out of fear of a pipeline explosion due to junta air strikes and shellings.

The pipeline has failed in the past, with significant impact for Posco International. In 2018, a pipeline disruption caused by a landslide on China’s side of the border led to a 50% quarter-on-quarter decline in profit. A pipeline failure on the Myanmar side could face significant repair-access issues amid deteriorating security.

Moreover, Hunterbrook Media has found that the Shwe gas project — described by Posco as “key to maintaining the company’s external growth and financial soundness” — has underperformed since its launch. Although the company has indicated the project would maintain a stable level of production until approximately 2034, production has declined 18% since its peak in 2019, even as the company continued to drill more wells in an attempt to maintain output. Exports to China appear to have declined since 2019 as well, according to Chinese customs data reviewed by Hunterbrook Media.

And yet, the Myanmar gas project is the business line that Posco International relies on the most. Profits from Shwe accounted for nearly a third of Posco International’s total in 2023.

POSCO WORKING WITH AN ENTITY CONTROLLED BY THE JUNTA ON A MAJOR GAS PROJECT AFTER OTHER OECD COMPANIES LEFT

Posco subsidiary Posco International is the majority shareholder (51%) and operator of the Shwe offshore gas project, which is a joint venture with the junta-controlled Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise and other foreign partners. MOGE collects revenue as a shareholder, as well as royalties, taxes, and profit shares as the regime’s representative.

The primary customer is China National United Oil Corp. (“ChinaOil”), which gets Shwe’s gas via a land pipeline that stretches from the initial intake station in Kyaukphyu, Rakhine State, across northern Myanmar to Ruili, China. ChinaOil is a subsidiary of China’s state-owned China National Petroleum Corp. The rest of the gas goes to the domestic market at a discounted price and is delivered to power plants and industrial sites in northern Myanmar.

Before the coup, Myanmar’s four offshore gas projects were teeming with major energy players from OECD countries. The OECD is a forum of mostly advanced economies, where the 38 member states seek to coordinate on and promote global standards on the “preservation of individual liberty, the values of democracy, the rule of law and the protection of human rights.”

Today, Posco sticks out as one of just two OECD companies still operating in Myanmar; Korea Gas Corp. — also a Korea-based company — has a minor, noncontrolling stake in the Shwe project.

TotalEnergies left the country in 2022, citing its inability to meet stakeholder expectations to stop funding the junta through MOGE. Mitsubishi and a Japanese consortium that included the Japanese government and oil refinery company Eneos also left, citing “social issues.” Chevron, after initially spending $3.7 million in the first half of 2021 on lobbying the U.S. Congress on “Burma energy issues,” as the AP reported, also gave in to shareholder pressure and eventually completed its exit earlier this month — two years after first announcing its intention to do so.

Posco not only stayed but continued its $788 million investment to drill new wells and upgrade existing platforms to improve production output. Since the coup, Posco has nearly doubled its annual operating profit from Shwe, from $181 million in 2021 to $386 million in 2023, according to its earnings statements.

The U.S. and EU views on the critical role MOGE plays in enabling the junta’s atrocities are clear: The U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctioned MOGE in September, with the Department of State accusing MOGE of providing “hundreds of millions of dollars in foreign revenues every year to the military regime’s coffers, which the regime uses to purchase weapons and military materiel from abroad.” The EU, which sanctioned MOGE in February 2022, has directly linked it to the junta’s airstrikes on civilians.

Posco has downplayed its financial ties to MOGE. In March 2023, Posco International defended its continued business with a contractual technicality: “Posco International is not a distributor of the proceeds from the sales of gas to any of the consortium partners.”

DEBUNKING POSCO’S NARRATIVE THAT IT SERVES THE MYANMAR PEOPLE

In a reply to Hunterbrook Media’s request for comment on its role in the country, Posco International said: “The reliable operation of the Shwe Project is directly linked with the stable livelihood of people in the country, and is the best possible way for us to protect people and communities in Myanmar from any further harm.”

Its response echoes what Posco International said in its 2022 Sustainability Report:

“The Shwe project serves as a main source of gas supply in the central northern region of Myanmar, and any disruption to its project execution leads to the suspension of fuel supply to multiple gas-fired power plants in Myanmar. This will significantly reduce the supply of electricity for the private-sector which is already under severe strain to cause direct damage to people’s livelihoods.”

Hunterbrook Media has found, however, that an increasing amount of Shwe gas is set to flow to junta-run steel mills with direct ties to weapons manufacturers, arms suppliers, and sanctioned entities. Homes and private businesses, meanwhile, have seen an increase in electricity shortages since the coup, amid the closure of multiple gas-fired power plants relying on Shwe gas as feedstock.

Posco Gas Supplies Junta Steel Plant With Ties To Sanctioned Arms Producers

Last May, the junta officially reopened a regime-owned steel mill in Myingyan, Mandalay region. Also known as No. 1 Steel Mill, it had been closed in 2017 by the civilian government because it was unprofitable. Just months after seizing power, however, the junta said it would begin work “as soon as possible” to recommission the steel mill, given the “large amounts of foreign currency needed in importing steel.”

Another junta-owned steel mill, located near the country’s largest iron mine in Pinpet, Shan State, is scheduled to reopen its doors as early as 2025. The Pinpet — or, No. 2 — Steel Mill also closed in 2017 due to unprofitability. It will process iron ore from a nearby mine to produce crude iron as feedstock for the Myingyan plant. The Pinpet plant and mine have faced strong opposition from local activist groups, who decry the severe environmental impact, land confiscations, and forced relocations caused by the operation.

Myingyan is connected to the Shwe pipeline as well as to an adjacent power plant that uses Shwe gas. The junta is working on repairing the pipeline that connects the Pinpet mill to Shwe gas.

The junta’s efforts to restart the unprofitable steel mills have led human rights organizations and independent Myanmar media to question the government’s claim that this surge in steel production is aimed at economic development. The junta has long sought to achieve self-sufficiency in the production of weapons-grade steel.

YouTube footage from the facility appears to show that the reopened Myingyan Steel Mill is equipped with a ladle refining furnace capable of producing high-grade steel used in weapons manufacturing, among other special applications.

Multiple known arms suppliers and regime figures responsible for arms procurement are involved in the recommissioning of the steel mills. The Pinpet Steel Mill is jointly operated by the junta’s Ministry of Industry and VO Tyazhpromexport, a subsidiary of Russia’s State Corp. Rostec, which has been sanctioned by the U.S. and is a known arms supplier to the junta, according to multiple Myanmar news outlets and the Russian government.

Sky Aviator Co. Ltd., a Myanmar arms broker sanctioned by the U.S., facilitated the transfer of euros to Tyazhpromexport for its help in restarting the Pinpet plant, according to a November 2022 document seen by the U.N. Special Rapporteur. Sky Aviator has been heavily involved in other arms-related procurements from Russia for the Myanmar military, including spare parts for fighter jets and other aircraft, according to the U.N. and local news reports.

A leaked Ministry of Defense document from January 2017 seen by human rights group Myanmar Now outlines the military’s intentions to “produce weapons of a higher quality” by using steel strengthened by adding certain ferroalloys. Ferroalloys are types of iron with high proportions of other chemical elements such as manganese or aluminum often used to make high-grade steel.

The ministry was interested in testing whether ferroalloys could be used to make arms and ammunition, tank, vehicle, and artillery parts, according to Myanmar Now. The human rights group also said the document showed that the junta was monitoring processes at the Myingyan plant involving ferroalloys.

Myanmar’s import of ferroalloys more than doubled in 2021 from the previous year and continued to increase in 2022, according to U.N. Comtrade data.

Another OECD company, Danieli Group, is linked to the steel mills. In a separate investigation, Hunterbrook Media shows that Danieli may be in potential violation of EU sanctions.

In response to a Hunterbrook Media email, Posco International said “it has been confirmed that the mills are currently not operational upon verification,” adding in a follow up that its source for this confirmation was “local networks.” As of April 12, the junta leaders appeared to urge engineers to continue to avoid halting operations at the Myingyan steel mill, according to Myanmar media, suggesting the mill is in operation. The company also added that “POSCO International does not have any direct contractual relationship with any steel mills in Myanmar.”

Civilian Electricity Shortages Are Spiking While Gas-Fired Power Plants Shut Down

While Posco gas is set to flow to the junta’s steelmaking, less is reaching Myanmar’s homes and businesses. Hunterbrook Media has found that four gas-fired power plants — out of at least nine in 2021 that almost certainly used Shwe gas as feedstock — have closed since the coup, with an additional power plant rumored to be closed.

A former local government representative told Narinjara News last July that three of the four power plants in Kyaukphyu — the starting point for the Shwe land pipeline — had recently closed due to a lack of natural gas from Shwe. The closures may have been led in part by widespread civilian boycott of electricity bills in protest of the junta, which caused financial losses for many power plants, according to a World Bank report.

With the majority of the gas exported to China, increasing the allocation of available gas to steel mills could further exacerbate the supply shortage to power plants for civilians. As of 2016, the World Bank estimated that the mills would consume roughly 20% of the projected domestic allotment of Shwe gas.

Even before the power plant closures, only a small minority of people in Myanmar benefitted from Shwe. Just half of the country is on the national grid. And only about 35% of the grid is powered by natural gas, compared to 53% by hydropower, further undercutting Posco’s claims regarding the importance of Shwe gas to citizens.

INTENSIFYING CONFLICT IN NORTHERN MYANMAR POSES RISK FOR PIPELINE DELIVERY OF GAS

Beyond reputational costs, Posco’s gas operation faces material risk from the exposure of the sole onshore pipeline to the conflict in northern Myanmar, which has intensified since October.

A supply disruption in 2018 caused by a landslide on the Chinese side of the border led to a 77% decline in profits from the gas project quarter on quarter, slashing the company’s total profit by half that year.

Even before the pipeline’s commissioning in 2013, industry experts and human rights advocates warned of significant security risks, given that the pipeline cuts through a historically volatile northern Myanmar region where ethnic armed organizations have contested the central government’s authority for decades. EarthRights International — which led an international campaign to bring greater transparency to the project — warned that pipelines in Myanmar “will present a simple, strategic, and ready target for an armed opposition force.”

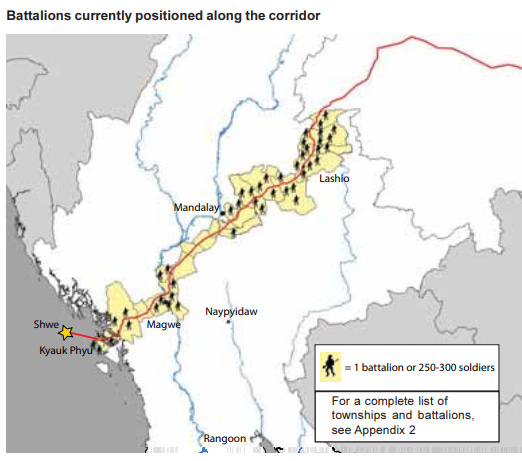

As early as 2009, Myanmar had stationed 44 battalions totalling about 13,200 soldiers along the pipeline to guard it against threats. Independent news outlets in Myanmar have reported that the junta also laid landmines along the pipeline in 2021.

Concerns about human rights abuses by the Myanmar Army attempting to counter such threats were among the reasons cited by the Norwegian Pension Fund for its decision to divest its shares worth $180 million in Posco International (then Daewoo International) in 2015.

The risk to the pipeline has increased since October, when major armed ethnic groups launched the most successful offensive against junta forces since the coup, taking control of vast swaths of territory in northern Myanmar. While violence along the northern region of the pipeline has subsided somewhat following a ceasefire agreement brokered by China in January, intense fighting has continued in northwestern Myanmar, including in the Kyaukphyu area, where Shwe gas is offloaded from the offshore pipe and routed onward via the land pipeline.

Some resistance groups, particularly those near the Chinese border, have pledged not to attack Chinese investments, including the pipeline, reflecting Beijing’s significant economic leverage. However, other anti-regime groups have brushed off China’s warnings, particularly amid growing public dissatisfaction with Beijing’s de facto support of the junta. In May 2023, a local resistance group attacked junta guards at a Shwe pipeline offtake station in the Mandalay region to protest a recent high-level Chinese meeting with junta leaders.

Moreover, the junta’s indiscriminate airstrikes risk inadvertently damaging the Shwe pipeline. These airstrikes and shellings have also targeted villages along the pipeline, including a village just 200 meters away.

In December last year, junta airstrikes in a village near the pipeline led residents to flee out of fear of a pipeline explosion. A spokesperson for a local human rights group urged international stakeholders not to invest in joint projects with the junta. As long as the military rules the country, she warned, such investments will always be targeted.

In just two months between February 1 and April 1, there were 55 air and drone strikes, 54 instances of shelling or artillery or missile attacks, 152 armed clashes, many of which included heavy shelling, and 30 incidents involving remote explosives and landmines, within 10 kilometers — and as close as 300 meters — of the pipeline, according to conflict event data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project.

See: Interactive version of above graphic on hntrbrk.com/posco.

Given diminished regime control over the northern territories and ability to provide adequate cover for its operations, pipeline personnel would find it challenging to repair damage caused by the fighting, potentially leading to prolonged disruptions to gas delivery — and significant revenue losses for Posco.

MYANMAR GAS, THE COMPANY’S “CORE BUSINESS,” PLAGUED BY UNDERWHELMING EXPLORATION AND PRODUCTION RESULTS

Earnings from the Shwe project are crucial for Posco International to execute on its growth and diversification plans, according to company disclosures. Yet the project has been checkered by disappointing exploration outcomes and underwhelming production output, Hunterbrook Media’s investigation shows.

Daewoo International, which developed the project starting in 2000, was a newcomer to the exploration and production industry. Posco bought Daewoo for about $3.1 billion in 2010 and has characterized Shwe as a “giant gas project” and “core” to its business.

In the years since Posco brought Shwe online in 2013, however, the project has consistently underperformed projections. Posco has revised output expectations down 48% and recoverable reserves down 53% from previous highs.

Posco International’s recent additional drilling, aimed at maintaining a stable plateau of production to last “approximately 20 years,” has yet to offset production declines.

In August 2022, Posco completed a $473 million expansion project to add seven new wells, with the stated goal of maintaining “a production capacity of more than 600 million cubic feet of natural gas per day (mmcfd).” But results have failed to hit that target. The project has produced a daily average that is 15% less than that amount.

Still, the company continues to forecast growth. At the end of 2022, for instance, Posco International predicted an annual production output of 207 billion cubic feet in 2023. Actual output was only 178 billion cubic feet, meaning the company had missed its forecast by 14%.

POSCO’S TIES TO THE JUNTA GO BEYOND SHWE GAS, FROM LUXURY HOTELS TO WARSHIP SALES

Shwe is not Posco Holdings’ only project in Myanmar. Its subsidiary, Posco International, owns 85% of a Mandalay hotel built in 2017, which sits on land leased from the Quartermaster General’s Office, an office responsible for securing supplies for the military sanctioned by the U.S. and EU.

Posco historically paid about $1.87 million in annual rent to the Quartermaster General’s Office, according to Myanmar Investment Commission records. In July 2022, the Australian Embassy came under fire after the investigative reporting group Justice for Myanmar revealed it had spent over half a million U.S. dollars at the hotel since the coup.

Separately, in 2019, Posco International brokered the sale of an assault ship to the Myanmar military by telling the authorities it was for humanitarian use — in an apparent attempt to bypass South Korean export control laws.

In 2017, the ship’s builder, Daesun Shipbuilding & Engineering Co. Ltd., had submitted a request to the South Korea Ministry of Defense for an export license to sell the assault ship to the Myanmar military. The ministry denied the request, in accordance with Korean export control laws and Korea’s obligations under the Arms Trade Treaty. Five months later, Posco successfully resubmitted the request with the claim that the ship would be used for "humanitarian purposes."

The ship’s plan, leaked by a former Myanmar naval officer, shows electrical and communications systems for guns — which were later installed by Myanmar — among other specifications consistent with the ship’s assault capabilities.

Posco’s efforts to facilitate the ship’s sale, including meeting with Myanmar military officials, took place against a backdrop of the military’s genocide of the Rohingya in 2016 and 2017, during which 740,000 Rohingya fled the country. In June 2022, the ship was sighted in Rakhine State — the site of the 2017 Rohingya genocide — carrying heavy artillery and rocket systems to ground forces deployed against ethnic armed groups in the state, according to open-source defense intelligence provider Janes.

In 2021, South Korean police launched an investigation into the potentially illegal transfer, targeting Daesun Shipbuilding, Posco International, and Korea’s Ministry of Defense for violations of Korea’s export control laws, after advocacy groups filed a complaint with the OECD.

Another Posco subsidiary, Posco Steeleon Co. Ltd. (formerly Posco Coated & Color Steel Co. Ltd.), operates and has a 30% stake in Myanmar-Posco C&C, a joint venture with Myanmar Economic Holdings Public Co. Ltd., also known as MEHL, a junta-owned holding company. A month after the U.S. sanctioned MEHL in March 2021, Posco said it would terminate the relationship with MEHL. Today, however, the Posco Steeleon website still claims that “work is underway to acquire MEHL’s stake in MPCC to ultimately end this joint venture.” Posco says the steel it produces in Myanmar “goes to retrofit residential roofs or build factory walls to improve the overall living environment for the people of Myanmar.”

“Posco is making history,” said Christopher Win, a Myanmar activist who fled the country shortly after the coup. “One day, people will bring up Posco as an example of how a company did business with a blood-drenched junta at the people’s expense, purely for profit.”

APPENDIX: POSCO INTERNATIONAL YET TO FIND A WINNING GROWTH SECTOR OUTSIDE OF STEEL AND NATURAL GAS, AS ITS DEBT MOUNTS

Since 2015, Posco International has invested in an array of business segments beyond its main steel operations, such as mining, textiles, agriculture, energy exploration, and power generation. But the company’s diversification efforts have been met with mixed results.

A review of Posco International’s earnings in the last five years shows that, while sales volumes from some of the company’s newer segments have increased, those same growth projects have yielded low margins — leading the company to acknowledge that “cash generation has been relatively insufficient.”

As the company waits for improved cash flows from its growth efforts, Posco International's net debt is at a recent peak.

Its natural gas and steel businesses contribute the most to Posco International's profits. Yet, the company's hype about its expanded foothold in the electric vehicle industry has been credited with increasing the company's share price — even while realized growth in that sector has remained minimal, given declining sales since 2021.

And while increased operating profits from other divisions could help the company offset any future underperformance from Shwe, inversely, snags in growing those segments could amplify the impact of underperformance by the Myanmar project.

Jenny Ahn is a geopolitical expert with a particular focus on the Asia-Pacific and has diverse overseas experience. She has an MA in International Affairs from Yale and a BS in International Relations from Stanford. Jenny is based in Virginia.

Blake Spendley joined Hunterbrook from the Center for Naval Analyses (CNA), where he led investigations as a Research Specialist for the Marine Corps and US Navy. He built and owns the leading open-source intelligence (OSINT) account on X/Twitter, called @OSINTTechnical (>900K followers), which now distributes Hunterbrook Media content. His OSINT research has been published in Bloomberg, the Wall Street Journal, and The Economist, among other top business outlets. He has a BA in Political Science from USC.

Daniel Sherwood joined Hunterbrook from The Capitol Forum, a premium subscription financial publication, where he was an Editor & Senior Correspondent, writing and managing market-moving investigative reports and building the Upstream database. Prior to The Capitol Forum, Daniel has experience conducting undercover investigations into fossil fuel companies and other research. He also served as an Honors Law Clerk in the Criminal Enforcement Division of the EPA. He has a JD from Michigan State University. Daniel is based in Michigan.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2024 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.