“WE’VE GOT A LOT OF PEOPLE KILLED HERE”

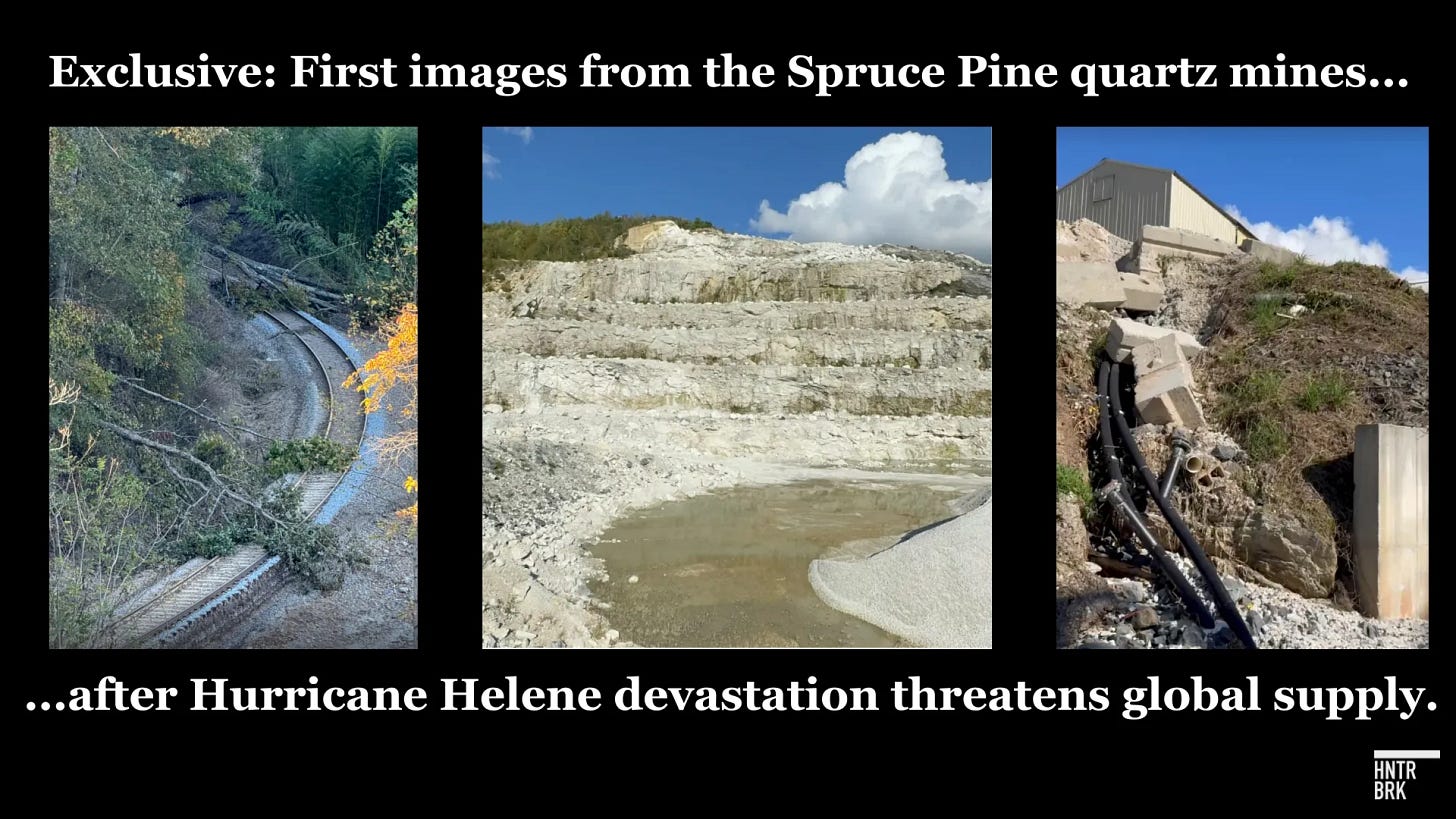

On-the-ground reporting in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene reveals devastation — and resilience — at the Spruce Pine quartz mines.

Author: Nathaniel Horwitz

Editors: Sam Koppelman, Jim Impoco

Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is long Ferroglobe Plc (NASDAQ: $GSM), long Nordic Mining ASA (Oslo: $NOM), and long Elkem ASA (Oslo: $ELK) at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. See website for full disclosures.

The only sound in the quarries was the hum of search-and-rescue helicopters scouring Appalachia for the survivors and corpses of Hurricane Helene. Earthmovers stood idle. Floodwater stagnated. Silty, quartz-speckled mudslides occluded access routes.

The twin mines of Sibelco and The Quartz Corp supply over 80% of the world’s high-purity quartz (HPQ), a rare mineral essential to many modern technologies, from cell phones and computers to solar panels and fiber optics.

Few if any small towns are more important to the global economy per capita than Spruce Pine, which had a population of about 2,000 prior to the hurricane.

If a supply shortage outlasts stockpiles, it could drive up prices for most of the tech sector. During site visits on the afternoon of October 2, there was no production at either quarry.

Sibelco and The Quartz Corp suspended operations on September 26 as the hurricane rampaged through the Southeast to descend on the mountain town of Spruce Pine, North Carolina.

The Quartz Corp has not responded to a request for comment. In a statement this morning, October 4, Sibelco said “restoring power remains crucial,” but its “operations have shown resilience” and “only sustained minor damage” — with the company “working closely with our customers to assess their needs and plan the restart of product shipments as soon as we can.”

A visit to Spruce Pine — walking through its quartz mines, processing facilities, and annihilated local infrastructure; talking with current employees, contractors, and local citizens; and then analyzing the scale of the damage through satellite imagery and geolocated videos posted to social media — revealed just how remarkable a timely return to production would be.

Hunterbrook was the first outlet to confirm flooding at an HPQ location on Sept 30, using open-source intelligence. Dozens of industry experts and major media outlets have speculated this week on how soon HPQ production can resume.

None, however, appear to have reported back from the mines and facilities themselves.

A Ghost Town Facility While Its Workers Aid Community

For about half an hour, there didn’t appear to be another soul at The Quartz Corp facility across the highway from its mine. The gate hung open. A company truck was bogged in a flood of clay-quartz mud next to a partly buried, plow-like device. A cascade of concrete blocks, rebar, and unearthed cables stretched from the entry road to the mid-level.

Down by the river, the railroad was covered in silt and fallen trees — just one of dozens of damage points on the railroad used by the mines, several observed directly, others cited in interviews.

Satellite imagery from Hunterbrook also confirmed that a stretch of the same railroad had been wiped out into the river south of the Quartz Corp facility, which looked like it had taken a direct hit from the flood.

In the ubiquitous silt over the rails was evidence of the only other recent visitor: pawprints. Near them, on the mud, half-sunk, a United States Army flag.

Alongside the railroad, miscellaneous facility equipment lay wrecked or askew. Wires meant to be underground hung loose in the air; wires meant to be airborne tumbled into the river and the shattered forest — where trees had slid down the mountainside.

Even at the upper levels of the facility, a pool of floodwater accompanied other structural damage. But no people. No one in the maintenance building, which from the outside appeared undamaged. No one at the milling plant.

Back at the open entrance, a sole employee of The Quartz Corp who said he previously worked at Sibelco explained why the facility was deserted: “They’re all out working. Folks are out helping the community,” he said.

When did he think the mine would reopen?

“I’m not avoiding your question, I don’t have a clue,” he continued, noting the damage to “the infrastructure, the power, and everything else.”

He said a downhill facility’s condition remained unknown. “We can’t get to it. Can’t get to it. There’s no …” he laughed bitterly, “What access?” It was an apparent reference to the difficulty of taking heavy machinery down the somewhat steep, flood-compromised road to the lower level, with the railroad out of operation.

As he spoke, a colleague who had entered the facility minutes earlier and pulled up in his truck added, “You know, with no communication, at all — yeah, we’re in the dark.”

A few minutes later, a third colleague arrived: the plant manager, Mark.

Asked about the timeline for reopening, he said, “I would have to give you our communications,” before going down the hill where he said he had a hotspot to retrieve the contact information.

A local construction contractor, Phillips Grading, used an 18-wheeler to take one of The Quartz Corp’s unused backhoes to a road restoration next to Sibelco.

Waiting for the return of the plant manager, The Quartz Group worker elaborated on the company’s decision to prioritize the community over restarting production.

“Everybody’s good to everybody around here. It’s not like the city,” he said. “If you see something cut around here, if you see trees cut, it’s been citizens, it hasn’t been the state, it’s not been DOT, they haven’t done anything. We’ve cut our own way in and out. Everybody’s helped everybody.”

The plant manager returned, explaining why he couldn’t predict the timeline for when they’d be mining again.

“Don’t have one. Don’t have one. We’ve got a lot of people killed here.”

***

As drivers approach the mine itself, The Quartz Corp quarry looms from the mountain, as a gigantic white staircase — stained by what looks like sludge dragged down from farther uphill by the storm.

At the entrance to The Quartz Corp mine, a MasTec electricity contractor crew had not observed any operations.

“Not that I know of,” said one of the linemen. “No earthly idea. I’m here to fix the power lines.”

There were multiple steps before power could return to the region, he said. “It all depends. We’ve got our safety protocols we’ve got to follow. We’ve got 10 crews, seven or eight up there working.”

He said it’s “a lot worse” than they’d expected.

One of his colleagues remarked, “Trees on every line,” adding that Duke Energy still needed to heat up its substation.

When would that happen?

“No earthly idea,” said the lineman.

A few hours later, farther down the road, one of a group of Duke Energy workers said “Substation still not up. Getting the lines up.”

How was that going?

“It’s going,” groaned one.“

You don’t wanna know,” quipped another.

Sibelco: A Community Lifeline Amid Devastation

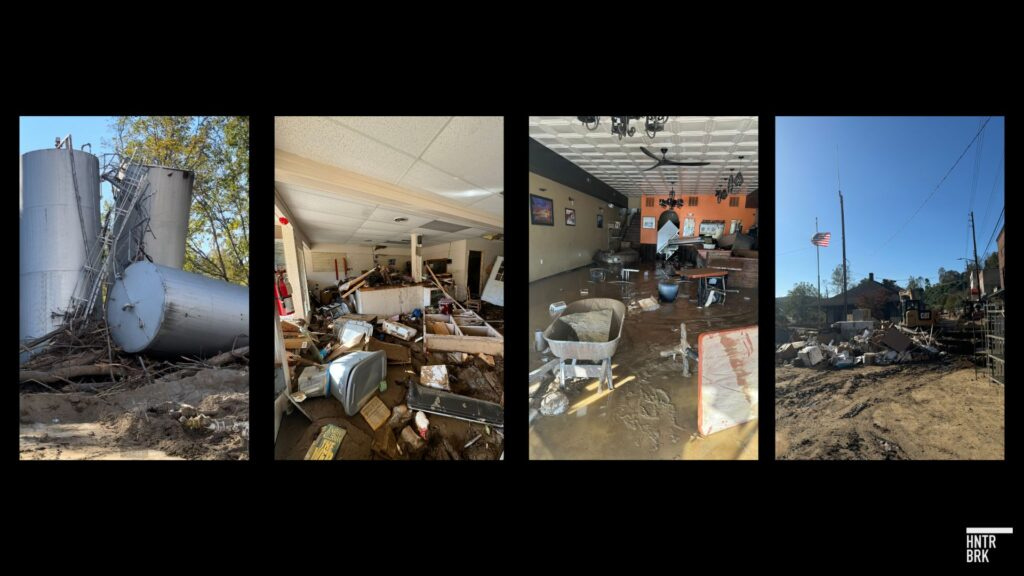

While The Quartz Corp stood silent with its workers helping out on the roads, Sibelco hummed with activity — not from mining, but from the tightly knit Spruce Pine community conducting its grim reckoning.

“This small community is a large player on the global stage,” said Rick Singleton, director of operations at Sibelco, standing by his silver Ford F-150 outside the flooded main office of Sibelco’s mining plant on Wednesday.

A 25-year employee of Sibelco — “born and raised” in Spruce Pine — Singleton knew the significance of the mines even as a kid. “I’m a second-generation miner here,” he said, adding that he had “talked about the applications” of quartz growing up.

These uses have exploded with the proliferation of technologies ranging from cell phones to generative AI — applications critical for the world and, right now, largely inaccessible in Spruce Pine, which has been almost entirely without electricity, water, Wi-Fi, cell, and landline service since Helene struck.

The same floods that had taken The Quartz Corp offline had transformed Sibelco into an impromptu community hub. The road through Sibelco’s facility — which for years was largely secret, due to the strategic importance of HPQ, and not opened beyond company use — had become a detour for the public and the National Guard.

Its corporate airstrip now doubled as a landing zone for supply deliveries.

“Our first focus is helping the local community,” Singleton explained. “We’re providing food, fuel, equipment, resources, and labor, to the local community, first and foremost, to help it get back on its feet. Then we’ll switch problems.”

“The mine itself,” he added. “Can’t tell you a whole lot about that, but it’s not as dire as you might read online.”

He pointed to a gas truck. “We’re having the gas delivered here for the people who don’t have access to fuel. It’s a difficult time. The community is rallying.”

The director of operations doesn’t think enough people in Spruce Pine — or around the world — recognize the criticality of Sibelco’s operations.

“To be honest, most of the people that aren’t involved here don’t understand the importance of the site for the global — they see it as a mine, a place for people to have good jobs. But as far as anything outside of that, most people don’t know,” he said, that only “limited locations around the globe” produce the kind of HPQ made in Spruce Pine.

Asked for a comment on the status over at The Quartz Corp mine and facilities, he replied: “That I cannot, I have no idea.”

In regard to Sibelco, he said only, “We’ll be hearing soon. I can’t give you a timeline,” and referred further questions on timing to corporate communications.

Four other Sibelco workers at the site shared skeptical views of the timeline.

“I don’t know dude, that’s a good question,” said one. “We gotta lot of work to do.”

Another pointed to the debris that had overtaken a bridge that extended from Sibelco to the far side of the river.

“There’s a pile of logs down there off the river. This all was flooded,” he said, adding that the community was “dealing with a ton.”

“It’s pretty devastating.”

A third remarked: “That’s totally up to Duke Energy and you know as far as that goes they’re working their butt off.”

“What nobody sees is the outlying areas is not close to the transmission lines, some of those people could be without power for months.”

Those outlying areas are also where Sibelco’s refineries are based.

At the front gate, a fourth Sibelco employee said: “Our other two plants, Crystal and Red Hill, are the refinery plants. And we don’t really know the whole damage until we actually get power and start everything up and see where everything’s at.”

“Similar condition as this, Red Hill plant I believe is the worse out of the two, but we still don’t know. I know the roads are real bad getting to it so it’s hard to get there anyway … We honestly can’t tell.”

“Our plant’s entirely down,” he added. “We don’t have no power, we don’t have water, and they’re expecting us to be, to have power Friday, but you never know until it actually happens.”

“We’re trying to help each other out, just do the best we can, be good neighbors.”

***

Several of the music and sports radio shows had become temporary emergency broadcast stations.

A volunteer at Mercy Chefs called the situation, “The Katrina of the Mountains.”

An anchor on one station remarked, “I have seen my Starlink more than my wife.”

“Ice is a hot commodity right now,” noted another broadcaster.

On the radio during the descent from the mines back toward Spruce Pine, a woman introduced an official, saying, “I will now turn it over to Ben Woody, who will cover additional details about our water system.”

“Thank you, Ms. Campbell. Again, Ben Woody, assistant city manager for the City of Asheville. And I’m going to try to give a comprehensive update as to where things are at with our water system. So, we have made measurable progress toward beginning the process of rebuilding our water system. However, I must remind the community that that system was catastrophically damaged and we do have a long road ahead.”

About an hour north of Asheville, the road ahead for Spruce Pine looked much longer.

“It was completely destroyed,” said Marie, standing on the main street of Spruce Pine, referring to a swath from the gas hub to the local park, both ruined. “It’s gone, it’s gone.”

“We’ve lived here all of our lives,” said her partner, Roger.

“We’re on town water, we don’t know when the town water will be —” said Marie.

“— We’re hoping to get power back by Friday,” said Roger.

“They’re hoping, but that’s probably just for the main drive,” said Marie.

Across the street, another couple — Nancy and Adrian — had checked on their friend’s restaurant, called Ranchero.

“We was looking there,” said Adrian. “They lost everything. The restaurant is not open anymore, lost everything.”

Outside the restaurant, José Jaurez, a sculpture artist and a welder for the utility truck maker Altec Inc. rode his skateboard and filmed earthmovers piling debris around what used to be the train stop.

“All I know right now there’s no water, no electricity, no Wi-Fi, no cell service.”

And regarding the mines: “They got washed out pretty bad, a lot of — I know they carry a lot of chemicals and stuff like that, I’m pretty sure it got into the water supply, but that’s just my guess.”

Sibelco and The Quartz Corp did not respond to questions about water contamination.

“The mines were like the biggest thing here, you know,” he said. “I’d go to the mines as a kid, we’d have field trips … Shake the rocks, you know, find gems.”

On the power restart: “I’ve heard different things, different gossip. I’ve heard we’re getting power by this weekend, some say two to three months, some say it’s going to take up to six months.”

His guess? “Electricity up-and-running? At least a month.”

Duke Energy did not respond to a request for comment.

Mary Wray, a teacher from nearby Little Switzerland, has lived in the area for 27 years and was trapped at Black Mountain for days until returning to Spruce Pine two hours earlier. “The school I work for is closed indefinitely, and the school is closed here indefinitely as well, from what I’ve heard.”

Spruce Pine, she said, “used to be a thriving community,” but these days, “the only business left is the mines.”

“I would love to see the mines put in more into our little tiny town,” she said. “There’s nothing for the young people, no jobs, I mean, unless you work in the mines.”

(Singleton, from Sibelco, said of his son: “He’s not going to be a third-generation miner. He’s big into horticulture.”)

Next door, David Sillman and Nate Schlabach looked into the town’s ruined music store, instruments sticking out of thick mud, fire alarm blaring. They had lived 24 and 21 years in Spruce Pine, respectively, and both worked in real estate.

“I live a block away. It’s a safe community where I don’t have any problem with my daughters walking down together and going to their music lessons,” lamented Schlabach.

Sillman reiterated that people were working on getting the power transmission line open: “It’s mostly ruined from here to Tennessee.”

The railroad, he said, was broken in “many places.”

The roads were also compromised. Sillman said, “226A, I came up yesterday … it’s rough, it’s eroded so bad, oh my gosh.”

Then he showed pictures of the mine’s main artery with chunks wiped out.

Schlabach added: “But trucking, the main road out of here is 226, that’s down for a really long time … the road broke away.”

He also shared a photo of a friend who turned his porch into a bridge.

But despite the disabled roads and railways, Nate speculated that the mines would reopen “by hook or by crook. They’ll figure out a way, because it’s valuable enough they’ll want to.”

He added that the mines have “a good reputation” and “a good safety record.”

Sillman added, “At the meeting this morning at the fire department, they were providing generators and tons of—”

Schlabach agreed, “Lots of heavy equipment they provide because they’ve got it local here … to extract minerals.”

Two women joined Nate and David.

One joked about the flooded café: “It smells like coffee too!”

“Petrol coffee,” Sillman quipped.

“We’ll rebuild, I guess,” said the other woman, Amanda Sanders — who, like Juarez, works at Altec on utility trucks. “I’m from Florida. I’ve been in dozens of hurricanes, but this is different. The terrain.”

Sillman said, on a sunnier note, “There will be a Starlink at the church tomorrow,” which would restore a degree of connectivity with the outer world.

On the next street over, Kevin Machoul smoked a hand-rolled cigarette while Mike “Llama” Soriano drank from a thermos. Soriano is a tattoo artist. Machoul is a volunteer, handing out food, looking for families, and making food plans for hard-to-reach people. He lived in an apartment on the main road that had miraculously not flooded, and he’d just gotten back from pet-sitting for a friend, where he’d then become trapped for three days by the hurricane.

“It’s a small community. Impoverished community,” said Kevin.

En route downstream back to Asheville, the roads had not improved. Somewhere above, President Biden flew on an aerial tour of North Carolina with the governor.

Then, a plume of smoke on the horizon, just beyond the turn-off into a trailer park.

The fire turned out to be a controlled burn across the river — and the wheels of a certain reporter’s truck turned out to be spinning haplessly in deep mud.

After about half an hour of shoveling and graveling the tires with the help of a father-son duo from the trailer park, the truck sprang free.

The father remarked, “Be careful going around like this. People are edgy. They’re on edge about looters. You’ll get shot.”

“You’re covered in mud. You better wash that off, it’s not regular mud,” the son added. “It’s from up the river, where there’s chemicals and dead people.”

Author

Nathaniel Horwitz is the CEO of Hunterbrook and sometimes moonlights as a reporter. He has contributed to The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Daily Beast, The Atlantic, The Harvard Crimson, The New York Times, and The Australian Financial Review. His first job out of high school was as a reporter at his local paper.

Editors

Jim Impoco is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek who returned the publication to print in 2014. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has a Master’s in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal — and published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work opportunities, and press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2024 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.