Buyer’s Remorse: How LGI Homes Lures Renters Into Buying Homes They Can’t Afford

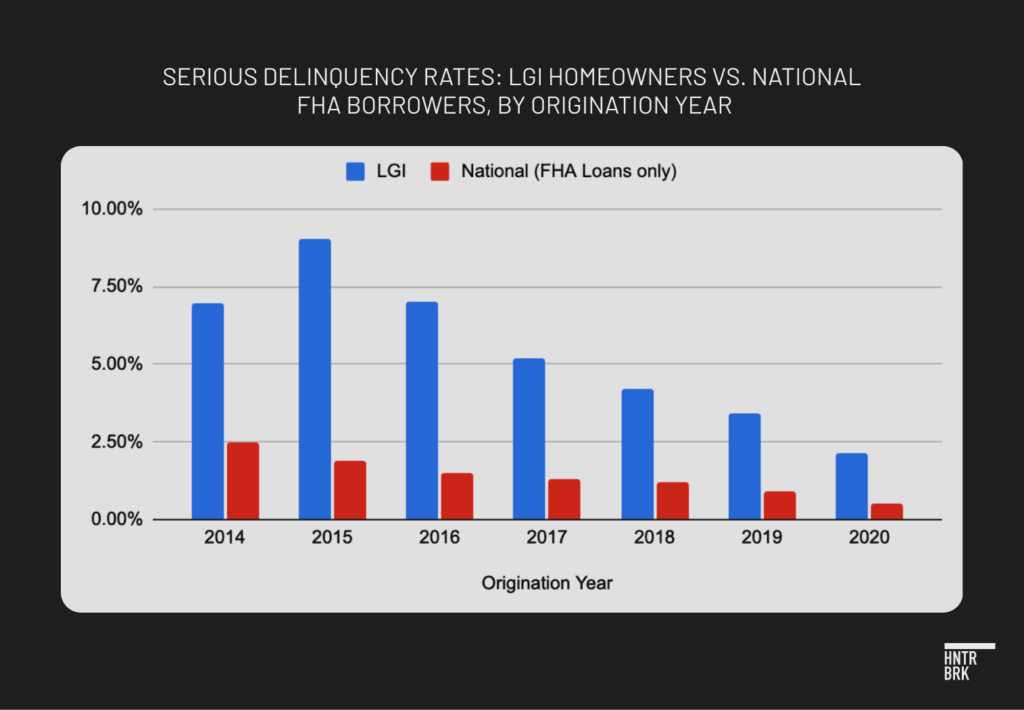

LGI homeowners were four times as likely to lose their home to a foreclosure than a typical FHA borrower — a pool already at higher risk — according to a Hunterbrook data analysis.

By: Jenny Ahn, Matthew Termine, Michelle Cera

Editor: Sam Koppelman, Jim Impoco

Hunterbrook Media’s investment affiliate, Hunterbrook Capital, does not have any positions related to this article at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Law is in conversations with firms across the country regarding potential litigation against LGI Homes. If you have experiences with LGI Homes and want to tell us about it, write ideas@hntrbrk.com.

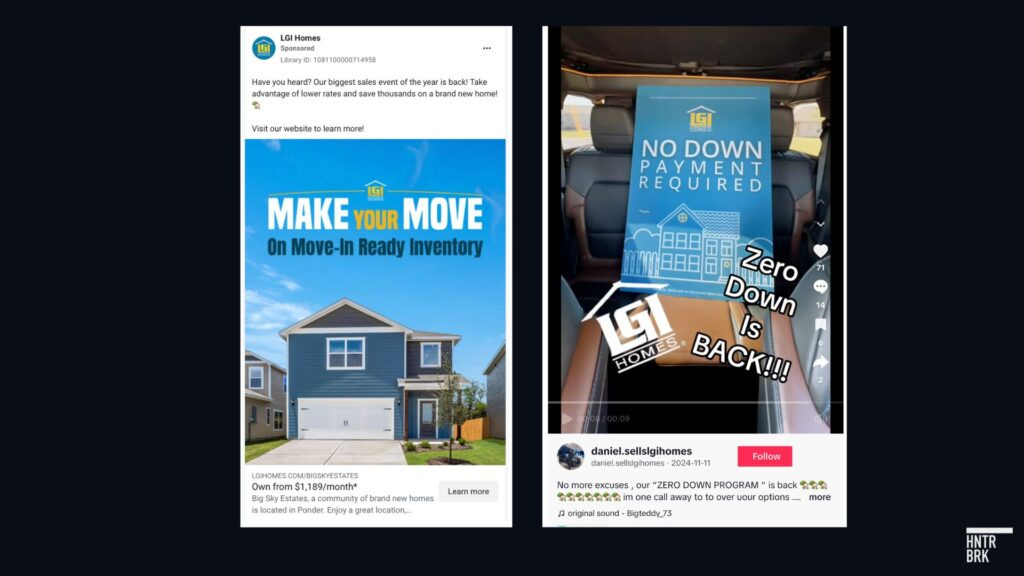

LGI’s “proven” sales strategy targets renters with unrealistic prices: LGI Homes built its business by advertising to renters with ads promising deceptively low prices that omit key costs like taxes, insurance, and HOA fees. A former employee said those who responded to the ads were often “very very low income people” who did not understand the fine print.

LGI buyers are four times as likely to face foreclosure than typical FHA borrowers: Hunterbrook’s analysis of LGI homeowners’ loan performance found that each cohort by purchase year from 2014 to 2020 was about three to 5 times more likely to face serious foreclosure threats than FHA loan holders nationally, even though FHA loans generally serve a higher-risk borrower base. (See how we conducted our foreclosure data analysis here.)

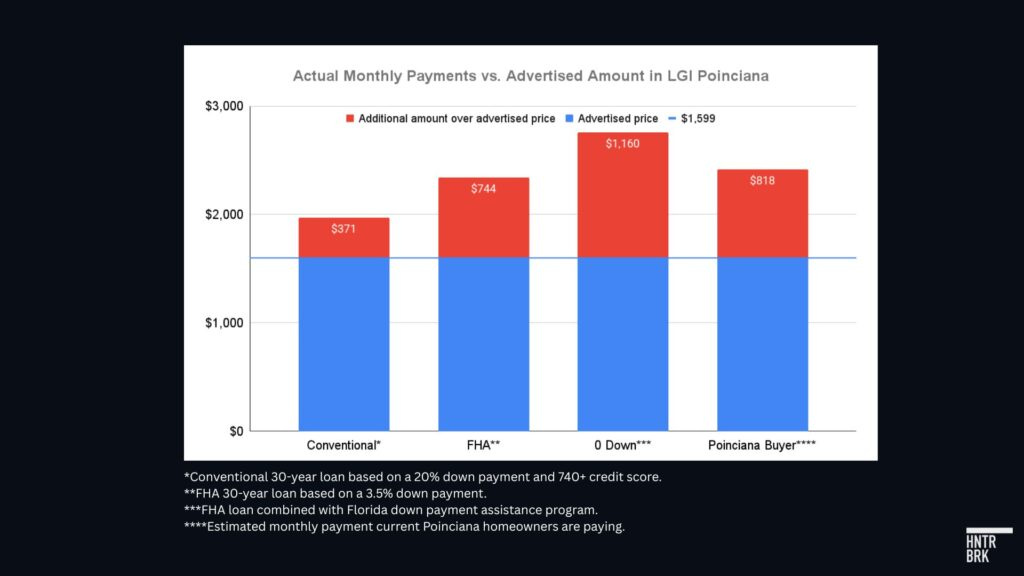

Actual monthly payments are likely 30% to 70% higher than advertised prices, Hunterbrook found: An LGI sales rep in a Florida office broke down the actual monthly payment based on different loan types, none of which came close to the advertised rate of $1,599 a month. Hunterbrook’s analysis of mortgage data suggests current homeowners in that community likely pay an average of about $2,417, or over 51% more than the advertised monthly payment.

Visitors to the sales office are greeted with a scripted, aggressive pitch intended to convert them into buyers that very day: LGI’s CEO described LGI as “really a sales and marketing company that sells houses,” with many of its sales reps coming from the “mattress industry.” A former employee said sales reps were expected to convince 20% of shoppers to purchase a home on their first visit. LGI promises to hold buyers’ hands through the daunting process of homebuying to make it “simple and enjoyable,” but homebuyers Hunterbrook spoke with said they felt “taken advantage of.” One expert told Hunterbrook that LGI’s sales tactics are “pretty much setting people up for failure.”

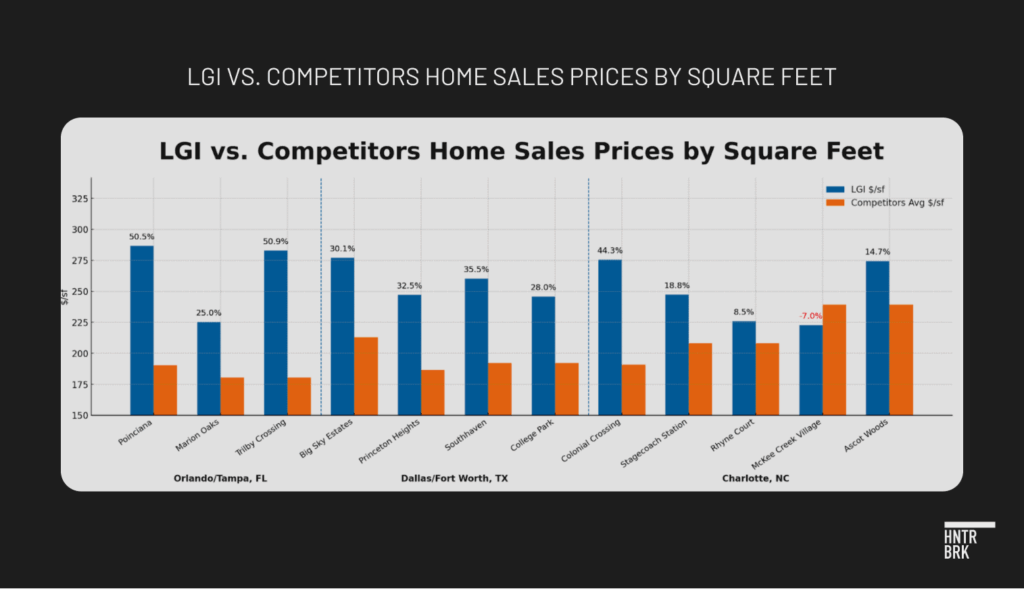

LGI charges significantly higher prices for its homes than its competitors do, while spending more on marketing: Even as rising interest rates and a deepening home affordability crisis led many other builders to lower their prices, LGI doubled down on marketing spend instead, their SEC filings show. A September snapshot of home prices in LGI’s top markets showed LGI homes were on average priced 28% higher per square foot than those of competitors.

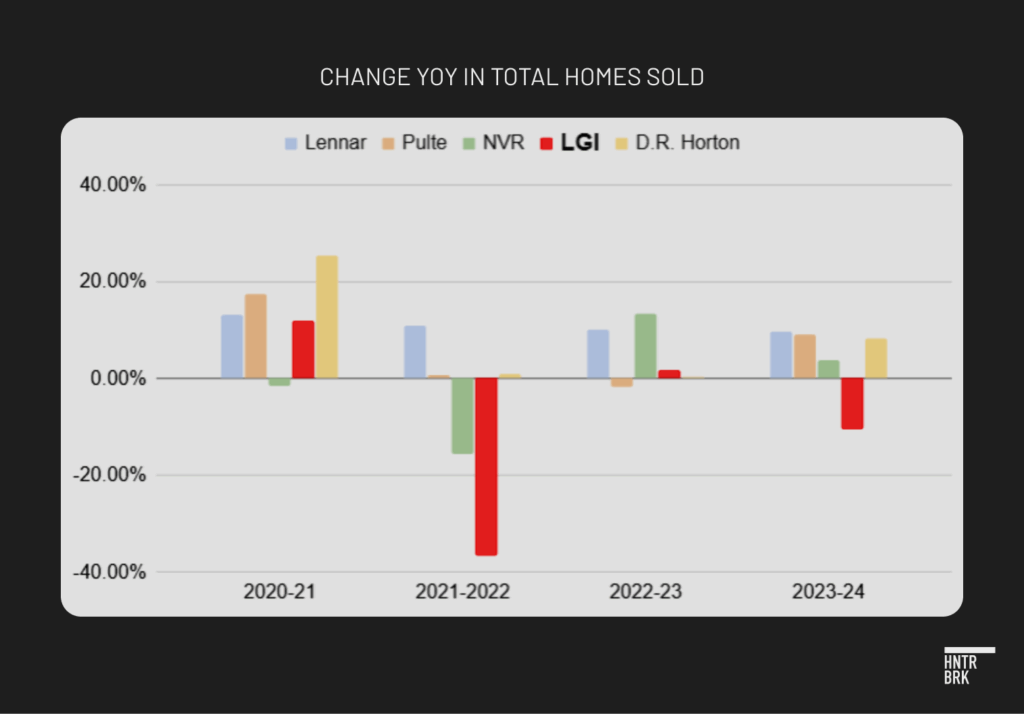

Prolonged affordability crisis testing LGI’s core model: Amid persistently high interest rates, signs of cracks are emerging in LGI’s “proven” strategy that rests on converting renters. Revenue is down almost 30% so far this year compared to 2021, and home sales are down by 45%. LGI belatedly began offering incentives and lowering home prices starting this year, despite the LGI CEO saying in 2020, “We’ve never been nor are we a builder that is offering incentives, like some of our peer group.”

Gregory Armstrong thought he’d found his ticket out of the rental trap.

In 2021, Armstrong, a veteran with disabilities, received a flyer from LGI Homes ($LGIH) advertising new homes for sale near his Dallas apartment. The flyer promised a brand-new home for a low monthly payment, blazoned in a big, bold font.

The message, Armstrong told Hunterbrook Media, was irresistible: “You can afford this much for rent, and you can afford a house that looks like this.”

Armstrong was paying a lot in rent. Why throw cash at a landlord, he reasoned, when he could build equity in something he owned?

Armstrong closed on the house for $296,900 with zero down in May 2021, he said — his first taste of the American dream.

It turned out that he couldn’t afford it.

After months of “really struggling, trying to hold onto this house, working all these overtime hours, whatever side work I could,” Armstrong fell behind on the payments.

By October 2023, the bank had seized his home.

“It was really hard for me to let my house go, because it was the first big win that I ever had. And all the time, these guys knew that they were selling me a house that I couldn’t afford.”

Armstrong’s story is no outlier. It’s part of a business model that appears to all too often target “retirees, people on Section 8, people who were just living on disability,” according to a former LGI sales rep — and convincing them to buy homes they often can’t afford.

“The training in-house would always be, ‘it doesn’t matter,’” the former employee said. “We would always be told, ‘You have to see it through. There’s gold in there.’”

Hunterbrook’s analysis of publicly available foreclosure data — methodology linked here — showed LGI homeowners are nearly four times as likely to lose their homes as the typical FHA borrower, itself a population of generally lower-income borrowers with a higher risk of defaulting on a loan.1

The LGI playbook is elegantly ruthless in its simplicity.

LGI’s system runs in two basic steps, Hunterbrook’s investigation showed: 1) target renters with predatory ads promising deceptively low prices, then 2): deploy high-pressure sales tactics to convince them to buy homes at inflated prices.

Founded in 2003, LGI built its business empire on a core “value proposition”: Owning is better than renting. CEO Eric Lipar, in 2022, said that as many as 95% of LGI buyers were renters, and that LGI sought to ensure that every community that it develops “has at least 50,000 rental units within 30 miles.”

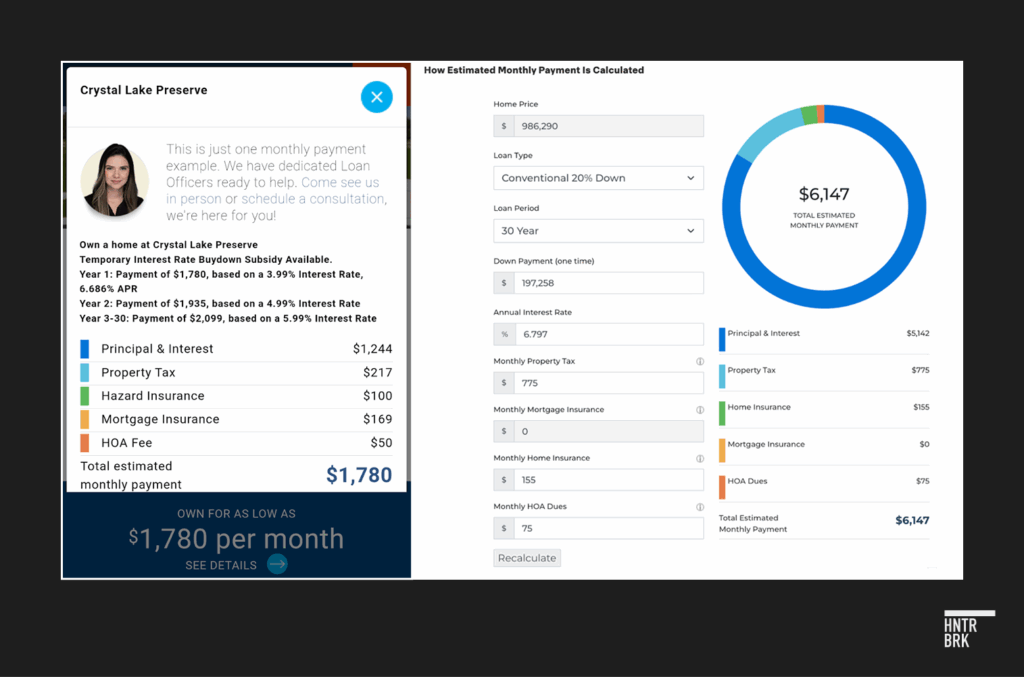

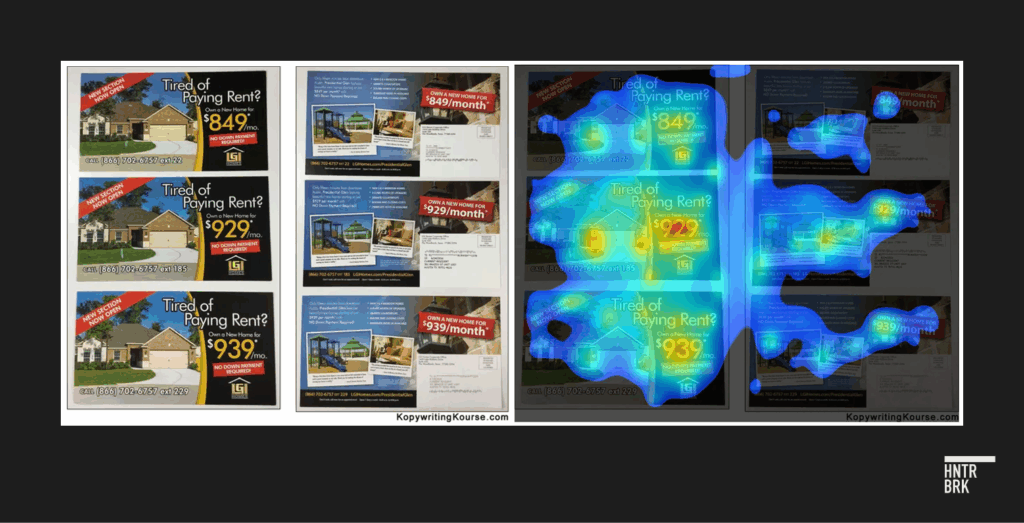

LGI sends out direct mail to nearby apartments and floods social media like Facebook, Craigslist, and TikTok with ads that display deceptively low monthly payments, omitting taxes, insurance, HOA dues, and other fees that could add at least 30% and as much as 70% to the headline price depending on the down payment and type of loan, according to Hunterbrook’s analysis.

The ads funnel curious shoppers into the sales office, where they are greeted by LGI sales reps armed with a highly scripted, aggressive sales pitch designed to convert them into buyers. It’s part of the “LGI Way,” as the company calls it.

Another former LGI sales rep who asked to be anonymous told Hunterbrook that “the expectation was to convert 20% of those appointments into a sale” on their very first day visiting the sales office.”

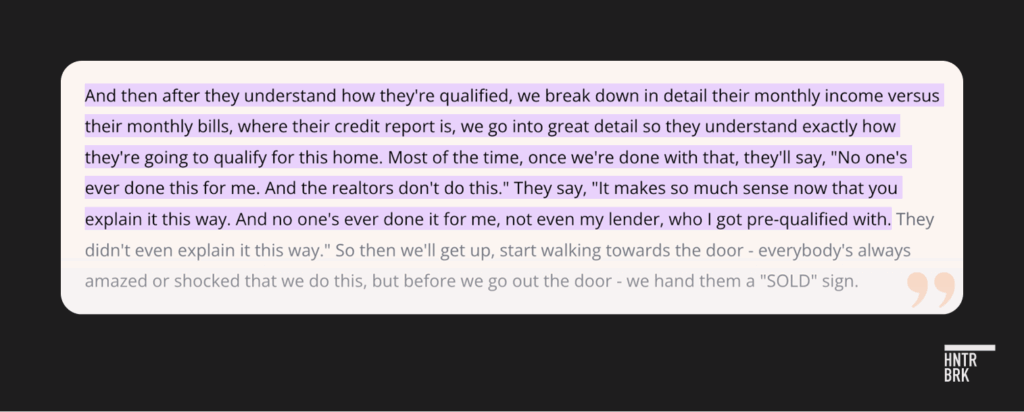

LGI sales reps “educate” renters on the benefits of homeownership and walk them step by step through the process. Even financing is designed to be “simple, enjoyable,” according to company materials, with offers of personalized financial planning advice to prospective buyers.

“It was really just, you know, really fast and simple, like they just had all of the paperwork printed out for me,” Armstrong recalled about the buying process. “I signed where they told me to sign, and you know, next thing I knew, I was a homeowner.”

It’s a “unique and highly successful marketing system proven to convert renters into new homeowners,” LGI told investors last year. It’s powered by a significantly larger marketing budget, longer sales office hours, and more sales staff per sales office than its competitors.

“If you have twice as many salespeople, you’re open longer, and you spend twice as much on marketing, you should have twice as many sales. And that’s really what our results have been,” Lipar said in a 2022 interview.

More bluntly, as Lipar put it on a different occasion, “We’re really a sales and marketing company that sells houses.” A lot of the salespeople come from the “mattress industry” and are “used to working with retail consumers and used to working weekends and nights,” Lipar told Investor’s Business Daily in 2020.

But while LGI pours money into marketing to brand itself as a company first-time homebuyers can trust, it appears to be routinely charging more for its homes than other builders in the neighborhood, Hunterbrook found.

In select metro areas in Texas, Florida, and North Carolina — LGI’s three biggest markets — LGI sells its homes at an average 28% markup compared to new homes in the same neighborhood built by its competitors, according to a Hunterbrook analysis.

Even as other builders lowered their home prices amid soaring interest rates since 2021, LGI doubled down on marketing rather than reducing home prices, LGI’s SEC disclosures show.

For Armstrong and many other LGI customers, the results of the company’s strategy have been devastating.

Homeowners interviewed by Hunterbrook, as well as many others across social media, said that LGI’s aggressive and misleading sales tactics led them to buy a home that was beyond their means.

“When you look at the math, no way that I could afford a house for $300,000 with a $2,000-plus a month of a mortgage,” Armstrong said in retrospect. “But I didn’t know that. I didn’t understand all of that. … like they understood it, but they knew that I didn’t. So they took advantage of the situation.”

One of the former LGI sales rep Hunterbrook interviewed said that they left in part because they were uncomfortable with LGI’s “bait and switch” marketing. They said many of those who responded to the ads were “very low income people” who weren’t financially savvy enough to understand the fine print disclaimers on the ad price that explains all the omitted fees.

“LGI in 2025 is still sending flyers to apartments. I’m like, come on.”

Their comment echoes those of numerous other former employees on job review sites like Glassdoor and Indeed who described LGI’s sales tactics as “deceitful,” in a “car salesman-like office,” where they “take advantage of people who don’t know better.”

Vanessa Perry, a marketing professor and interim vice dean of the George Washington University School of Business, said that LGI’s tactics — from the deceptively low monthly payments advertised to the hands-on sales process — may be designed to psychologically induce buyers to make an unwise purchase.

“Between the aggressive sales pitches and the anchoring in the sort of misleading advertising messages, they’re pretty much setting people up for failure.”

LGI did not respond to Hunterbrook’s request for comment as of publication.

In a weirdly twisted touch, LGI apparently gave one of its customers a jar of jellybeans labeled “Buyer’s Remorse Pills” as a closing gift.2

Targeting Renters with Misleading Promises

In June, a Hunterbrook reporter visited one of LGI’s new housing communities in Poinciana, Florida, about 50 miles south of Orlando.

The roads leading to the development were lined with numerous LGI signs and banners advertising the company’s “$0 down” offer.

Homes here go for as little as $1,599 per month, the website said.

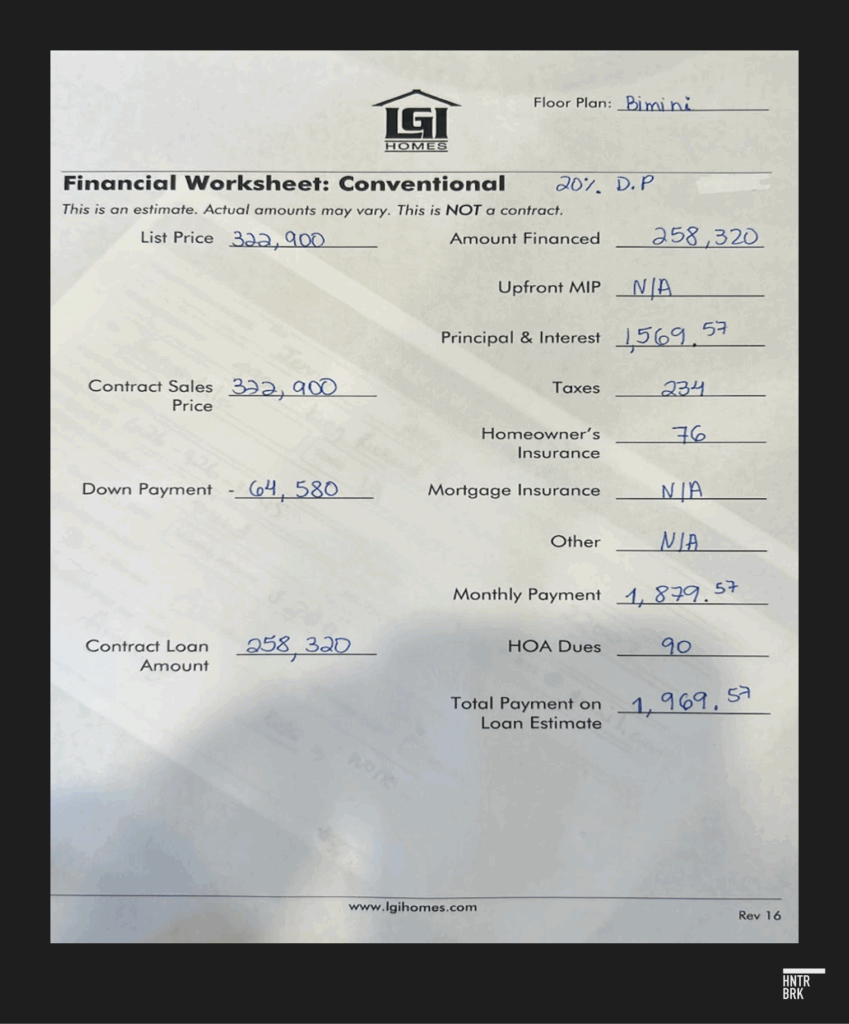

In reality, as the reporter discovered during the visit, none of the financing options that the sales rep offered came close to the advertised rate.

The cheapest possible monthly rate LGI could offer came out to $1969.59, almost 30% over the advertised price, when homeowner’s insurance, the HOA fee, and taxes were added.

That’s a monthly payment based on a 20% down payment that most LGI buyers in Poinciana probably can’t afford, according to Hunterbrook’s analysis of proprietary mortgage and deed of trust data. The data showed that nearly four out of five of the 174 homebuyers in Poinciana in the last five years who received financing made a down payment of 5% or less.

That means, even by a conservative estimate assuming the most favorable rate reserved for the highest credit score borrowers, the average Poinciana resident is likely paying at least $2,417, or over 51% more than the advertised monthly payment.

If the buyer were to opt for the “0 down” program the Poinciana sales rep offered, the monthly payment becomes $2,758.88 — more than 70% above the advertised price.3

When asked, the sales rep kindly explained that the only way to achieve the advertised price of $1,599/month is to put down $130,000 — nearly 42% of the total sale price at the time.

Advertised Prices “Far From Reality”

Across social media sites, LGI similarly advertises its homes using monthly payments that exclude taxes, insurance, and HOA and other fees — a practice rarely found in the industry, according to Hunterbrook’s review of the advertisements of leading homebuilders. Builders commonly advertise using the total price of the home rather than an estimated monthly payment, and those that do advertise monthly rates include a more transparent and realistic breakdown of the payments by including taxes, insurance, and other fees.

“The prices were always so far from reality,” a former LGI sales rep told Hunterbrook, saying she kept asking the management to make the ad prices on the website “close to reality,” until she eventually just left the company.

“Most of our homes for a monthly payment, you’re talking like anywhere between $2,300 to $2,800 a month. Like, you could at least put $2,000 on the website? You know what I mean? But to put $1,299, come on.”

Multiple LGI buyers told Hunterbrook the actual mortgage payment they ended up with was significantly higher than — even double, in one case — what they had initially expected based on the ads. All too often, their home ended up in foreclosure.

“We know that consumers tend to latch on to the advertised number, then use that number to adjust their perceptions of the prices after that,” Perry explained.4 “At that point, they may not actually pay as much attention to subsequent numbers, for example, the paperwork that they get when it’s time to actually close on the loan.”

LGI’s marketing may also include another misleading claim to entice renters: Compared to rent, they say, which can go up every year, if you buy a home, “Your payment won’t get higher and higher each year.” But as any homeowner knows, taxes, insurance, and HOA fees tend to rise over the years, increasing the total monthly payment.

Even the more realistic monthly payment that includes all the fees like taxes and insurance, which LGI will eventually share with the buyer, may be artificially low. At the Poinciana office, the $76 monthly insurance cost used to calculate the monthly payment appeared extremely low for Polk County, where the average insurance rate for single family homes last year was $2,697 annually, or about $225 per month, according to the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation.5 The sales rep explained that the insurance cost was based on a promotional rate through LGI’s partnership with its joint venture partner, Heimer Insurance Co., and was subject to change after the first year.6

Skirting the Legal Line on Deceptive Marketing

Experts Hunterbrook spoke with agreed LGI’s marketing may be misleading, but pointed out the potential difficulties of establishing clear legal wrongdoing. Perry, who also was an expert appointee at the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and served as a senior advisor to the secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, explained that homebuilders “operate in a gray area as to whether or not it would be considered outright deception from a legal standpoint.”

“But it certainly is misleading,” Perry said, adding, “And it’s hard to argue that it’s not intentionally misleading.”

Umit G. Gurun, a professor of accounting at the University of Texas at Dallas who studied deceptive advertising by lenders during the subprime mortgage crisis, told Hunterbrook that companies often exploit behavioral biases and financial illiteracy, making seemingly attractive offers that are not truly achievable or sustainable. He pointed out, however, that proving deceptive advertising typically requires demonstrating a clear, quantifiable harm to consumers. And that’s hard to do when comparing the cost of renting to that of homeownership, which involves personal preferences and unquantifiable aspects like the value one attaches to owning a home and amenities like a backyard or garage.

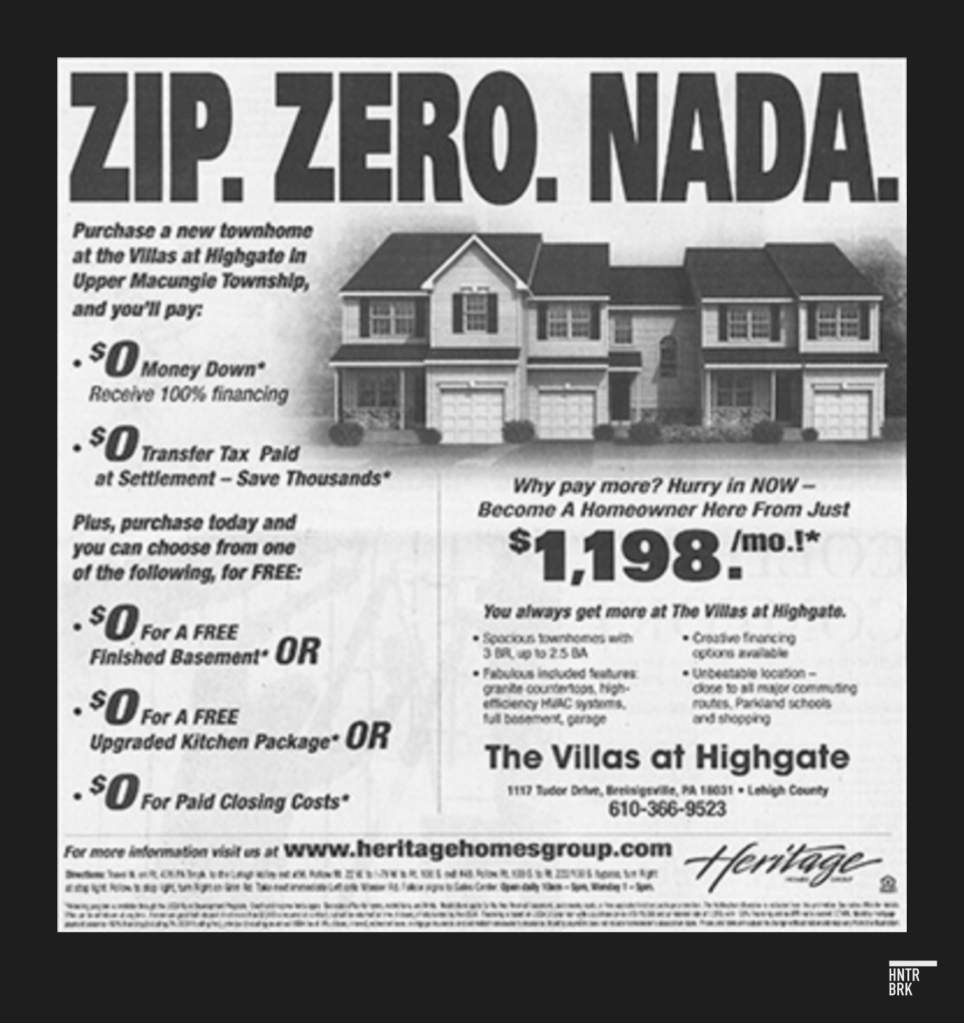

But such marketing tactics designed to draw shoppers have not gone unnoticed by federal regulators. The Federal Trade Commission in 2014 charged Pennsylvania homebuilder Heritage Homes with deceptive marketing for advertising low monthly payments with no down payment, without adequately disclosing terms such as “credit and income restrictions” and annual fees. Heritage Homes “tricked consumers into believing they’d found an affordable mortgage with very favorable terms,” the FTC said.

Lipar, himself, reportedly has faced scrutiny over similar practices in the past.

In a 2004 lawsuit, mobile-home owners in Montgomery County, Texas, accused Lipar, as owner of The Lipar Group, of promising low monthly mortgage payments that later more than doubled, according to Houston-based news Chron. The homeowners also accused Lipar of inflating home values by an average of $55,000 above the actual market value. Lipar, through his attorney, denied the allegations, and it was unclear from court records whether or how the case was eventually resolved.

Using Sales Tactics To Engineer Conversions When the Numbers Can’t

The marketing blitz is just the first part of the LGI playbook. It’s intended to funnel renters into the sales office, where they become captive audiences for the company’s high-pressure conversion tactics.

LGI sales reps are trained to bring any callers inquiring about an ad into the office regardless of whether they can actually afford a home, a former LGI sales rep told Hunterbrook. “Even on the phone, you know that they cannot afford the whole house. But the training is you’re not allowed to tell them that before. The training is you tell them ‘no problem.’”

Shoppers who visit the LGI sales office are greeted with a scripted two-hour pitch by zealously trained sales reps, designed to persuade renters to sign on the dotted line. “Our goal was to have a client sign a contract that day that they toured a house,” a former LGI sales rep told Hunterbrook. “Yeah, I would say it was high-pressure.”

It’s the “LGI Way” — a highly successful “direct to consumer” marketing model “proven” to convert renters into new homeowners.

“Together, we discuss your finances, mortgage qualifications, and assess your current income and bills,” LGI promises buyers. “Together, we will calculate your low monthly payment down to the last cent.” LGI even offers personalized programs to help would-be homebuyers lower their debt to improve their credit score, according to a former employee.

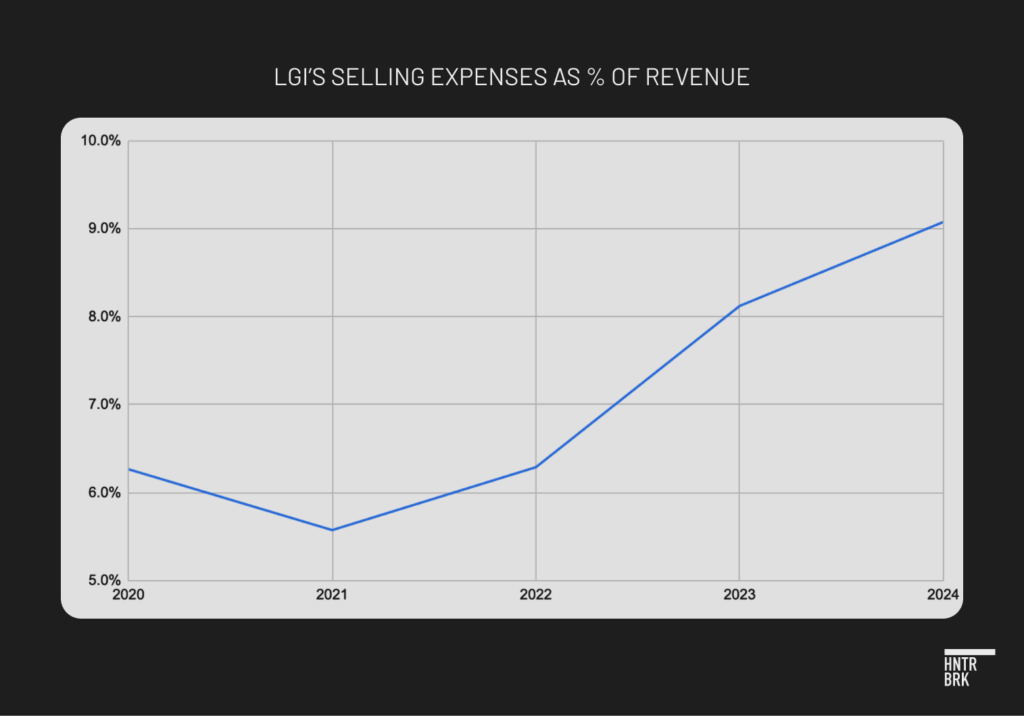

LGI backs up this model with a sales and marketing budget that’s significantly higher than its peers. In fact, controlling for revenue, LGI in 2024 spent 30% more in selling expenses — a component of selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses that includes the cost of advertising, marketing, sales commissions, and operating sales offices — than what the top four builders, D.R. Horton (DHI), Lennar (LEN), Pulte (PHM), and NVR (NVR) spent on average on their entire SG&A, according to the SEC disclosures Hunterbrook reviewed. LGI has historically also operated as much as 50% longer hours at their sales offices than its peers, staffed with “three to four times as many sales people per community than other builders,” according to Lipar.

Foreclosures: The Human Toll of LGI’s “Proven” Strategy

But that same strategy that’s driving the company’s growth is also driving buyers to ruin: LGI homeowners face foreclosure threats at rates that are nearly four times the national average.

Hunterbrook’s analysis of the performance of mortgage loans on LGI properties found that almost 6% of all LGI homeowners who purchased between 2014 and 2020 faced foreclosure notices. Their delinquency rates on average were four times higher than the national average for FHA loans. This is likely a conservative comparison, since some LGI buyers also take out conventional and VA loans, which are typically far less delinquent than FHA loans, suggesting the gap may be even wider. (See our methodology on how we conducted our foreclosure data analysis here.)

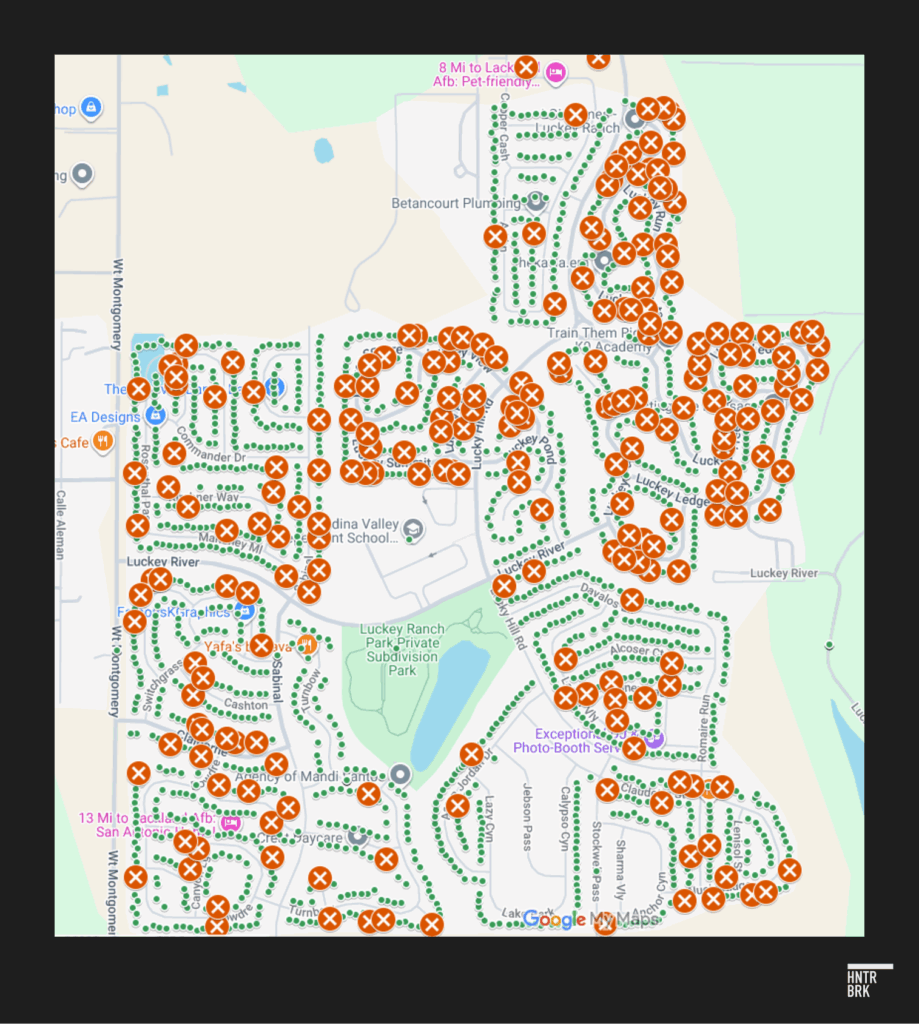

In one remarkable finding, Hunterbrook’s analysis of county land records showed nearly one of every five buyers who closed on their new LGI home in a master community in Bexar County, Texas, since the community opened in 2011 has faced at least one foreclosure notice.7

A Glimpse Inside a Foreclosure Machine

“I can’t say I’m surprised to hear that,” a former sales rep said to Hunterbrook, when told about the high foreclosure rates among LGI buyers. “You can imagine the kind of person who wants to live in a whole brand new house and pay only $1,399,” she said, adding that most of the clientele were retirees, “people who are making like $13 to $15 an hour,” and people on disability.

“And then the training in-house would always be ‘it doesn’t matter.’ … They’ll tell you, you never know, if somebody sees the house and really, really loves it, they may go bring a cosigner.”

For one LGI shopper, pressuring an unqualified buyer to find a cosigner — or ask a relative for money — seemed like part of the sales manual.

After initially being led to believe she qualified for a zero-down U.S. Department of Agriculture Guaranteed Loan on a new LGI home in Minnesota, in 2022, Marissa, who asked to be identified by her first name only, said LGI told her that her credit score was too low. They told her to add her grandfather, who was in hospice care, as a cosigner and said she could refinance the next day.8

Then LGI told her she still didn’t qualify and needed to make a larger down payment. When she said she didn’t have the money, they told her to draw from her grandfather’s savings — a hard no for Marissa.

Marissa said they probably knew she wouldn’t qualify for the zero-down from the beginning. “They knew the credit score all along, and they knew how much money obviously we had,” she said.

“I feel, at the time going from renting and being younger, we were kind of preyed on.”

Marissa and multiple other LGI buyers also said LGI discouraged them from having a realtor represent them and sometimes even flat out said they couldn’t.

“Direct to consumer model limits reliance on realtors,” LGI said in a recent investor presentation.9

But a conflict of interest may be baked into a model in which sales reps serve both the buyers’ interests and the company’s bottom line, according to Perry. “The builders don’t necessarily have the same kinds of standards for disclosure and for representation,” Perry explained. “They’re both providing the property, providing the loan, and providing the financial advice, which in and of itself is a conflict.”

While Marissa was able to pull out of her contract, others haven’t been so lucky, in hindsight.

Tameka Lowe, whose husband purchased an LGI home in 2019, said they didn’t get a realtor because they were “ignorant.” Their home was in the process of being foreclosed as of September 2025, after the Lowes failed to keep up with increasing payments, even after restructuring the loan.

They were “selling it as something affordable, something fast and easy, and that your mortgage would be at this set price,” she recalled.

“But like I said, we didn’t know.”

Too Little, Too Late? LGI’s Playbook Under Strain

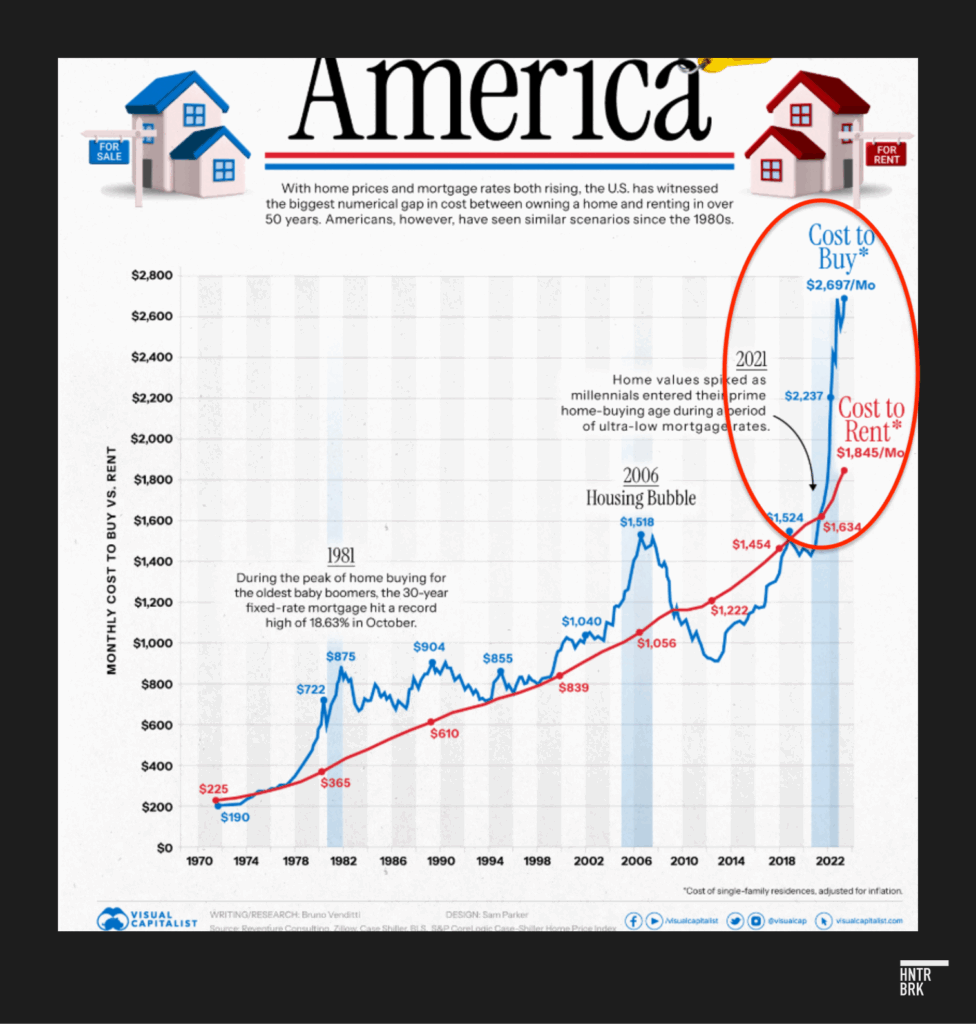

For much of its history since its 2013 IPO, LGI’s core value proposition to both investors and customers — that buying is better than renting — was supported by broad market conditions: Historically low interest rates made home ownership a cheaper option than renting for the majority of renters.

That changed after 2021, when rising home prices and interest rates pushed the average cost of buying above the cost of rent for most Americans, according to numerous studies, making it less clear that buying made financial sense.

Lipar himself admitted to investors earlier this year that “that gap between what the customer is paying for rents and what their monthly payment will be on a mortgage” has “really never been wider.”

LGI’s response? Double down on marketing — rather than bringing down home prices as many of its competitors had done.

“So we’re spending additional money on marketing” to maintain the company’s conversion pace and profitability, Lipar said during the same call.

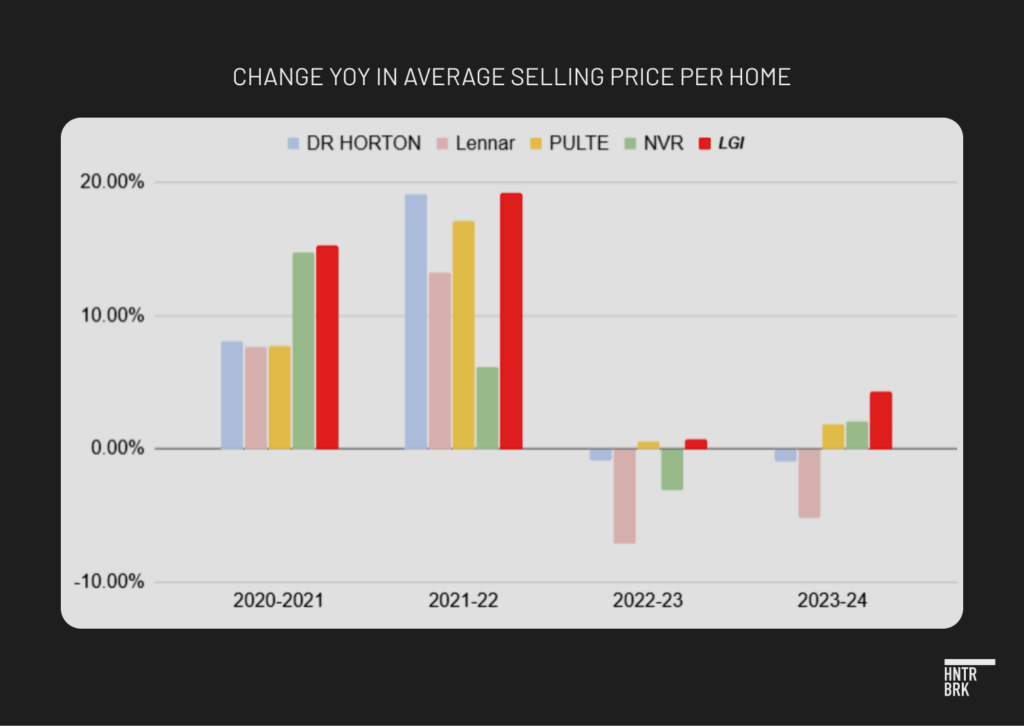

At the same time, LGI continued to raise home prices through the end of 2024, though not as aggressively as before, while D.R. Horton, Lennar, and NVR — three of the nation’s top four homebuilders — have lowered their prices at least once since 2022. Pulte Homes, the third-largest homebuilder in the country, which also did not lower their home prices, operates in a higher end of the market than LGI and the other top builders.

Only starting this year did LGI begin lowering its average home sales prices including by offering incentives “to bridge the affordability gap and put homeownership within reach of as many customers as possible,” according to its most recent quarterly SEC disclosure.

That’s a hard pivot from 2020, when Lipar told CNBC: “We’ve never been nor are we a builder that is offering incentives, like some of our peer group.”

It also suggests eroding confidence in LGI’s “proven” playbook targeting renters, under the deepening housing affordability crisis. LGI is selling 45% fewer homes per community per month this year so far than it did in 2021, when LGI reached its peak revenue during a period of low mortgage rates and COVID-era demand for housing units. LGI in February forecasted $2.2 billion in revenue for 2025 — almost 30% less than what it was in 2021. A few months later, in August, LGI announced that the prior forecast couldn’t be relied on and pulled the guidance.

LGI appears to have suffered a worse sales decline than its peers, as well.

And the discounts appear to be too little, too late: An early September snapshot of new home sales prices suggests LGI home prices continue to be inflated compared to an average of those of its competitors.

In Hunterbrook’s analysis of randomly selected neighborhoods in three of LGI’s top markets — Orlando-Tampa, Florida; Dallas-Fort Worth, Texas; and Charlotte, North Carolina — LGI homes as of early September were priced anywhere from about 9% to 51% more per square foot than those advertised by the top 10 national builders within a 12-mile radius, with the exception of one LGI community in Charlotte.

And for LGI homebuyers who have already lost their homes, the damage can’t be undone. All they can do, it seems, is warn other shoppers not to make the same choice they did.

“You need to make sure that you have someone with you that you can trust that’s good at the math and understands what the home-buying process consists of,” Armstrong said, when asked if he had any advice for future buyers.

“Because if you don’t know, and you don’t have someone on your side who’s going over these numbers with you, who’s telling you what’s right and what’s not right, you’re gonna get in a situation that’s gonna end up hurting you in ways that you can’t even imagine.”

Authors

Jenny Ahn joined Hunterbrook after serving many years as a senior analyst in the US government. She is a seasoned geopolitical expert with a particular focus on the Asia-Pacific and has diverse overseas experience. She has an M.A. in International Affairs from Yale and a B.S. in International Relations from Stanford. Jenny is based in Virginia.

Matthew Termine is a lawyer with nearly five years of experience leading the legal team at a mortgage technology company. In 2017, Matt was credited by the Wall Street Journal, among others, for identifying suspicious mortgage loan transactions that led to several successful criminal prosecutions, including that of a prominent political operative and the chief executive officer of a federally chartered bank. He is a graduate of Trinity College and Fordham University School of Law. He grew up in Old Saybrook, Connecticut and now lives in Brooklyn with his wife and three children.

Michelle Cera trained as a sociologist specializing in digital ethnography and pedagogy. She completed her PhD in Sociology at New York University, building on her Bachelor of Arts degree with Highest Honors from the University of California, Berkeley. She has also served as a Workshop Coordinator at NYU’s Anthropology and Sociology Departments, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and innovative research methodologies

Editors

Jim Impoco is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has a Master’s in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

This investigation underwent dedicated fact-checking. Design contributed by Alexander Spacher.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work opportunities, and press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2025 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided “as is” without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.

FHA loans are federally-backed loans overseen by the FHA — or the Federal Housing Administration — intended to help borrowers with lower credit scores or a smaller down payment to purchase a home

What LGI calls the “$0 down” program is actually a combination of a Florida down payment assistance program available for first-time homebuyers and an FHA loan. The Florida program allows buyers to borrow up to $10,000 for the down payment and closing costs, which the borrower can then use to cover the 3.5% down payment required for the FHA loan

Advertising alluringly low but unrealistic prices is a marketing tactic that exploits “anchoring bias” — a psychological tendency for buyers to use that initial reference point as an “anchor” for what something should cost, then to keep returning to that number even after learning the real costs are higher

The Florida study does not mention the average home value, but according to Zillow, the average value of homes in Polk County is $301,412 — compared to the advertised LGI home in Poinciana of $332,900.

Hunterbrook found that Heimer Insurance Co. and LGI’s subsidiary, LGI Insurance Solutions LLC, run a joint venture that offers homeowner’s insurance to LGI buyers. This is a common structure that allows two independent “settlement service providers” — i.e., Heimer, as an insurance agent, and LGI, a homebuilder — to collaborate in serving mutual customers and share profits without violating the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act. RESPA prohibits kickbacks and referral fees in mortgage and insurance transactions but allows for affiliated business arrangements, if certain conditions are met, including that the only thing of value received via the arrangement is return on ownership interest.The promotional rate, however, raises the question of whether LGI is receiving additional benefit from the arrangement outside its ownership interest.

Hunterbrook found 235 unique addresses in Luckey Ranch, a master community built by LGI, that were associated with at least one foreclosure notice since 2011, according to Bexar County land records. According to the Bexar County Appraisal District, there are currently 2,457 parcels in Luckey Ranch.

Marissa later found out that was false. She said: Lenders often require at least six months after closing before allowing refinancing.