CAVA: FILTH FLIES, “C” SANITATION GRADES, FDA LISTERIA SWABS, SNEAKY SEED OIL, INSIDER SELLING, AND THE DIARRHETIC FALLOUT OF FAST GROWTH

“Eventually it got to a point — sorry, this is graphic — where I had to clean up his vomit that was in the bathtub because he couldn’t control how fast it was coming up.”

By: Eve Peyser Sam Koppelman Michelle Cera

Editor: Jim Impoco

***

Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is short Cava Group (NYSE: $CAVA) and long a basket of comparable securities including Sweetgreen (NYSE: $SG) and Shake Shack (NYSE: $SHAK) at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. See website for full disclosures.

***

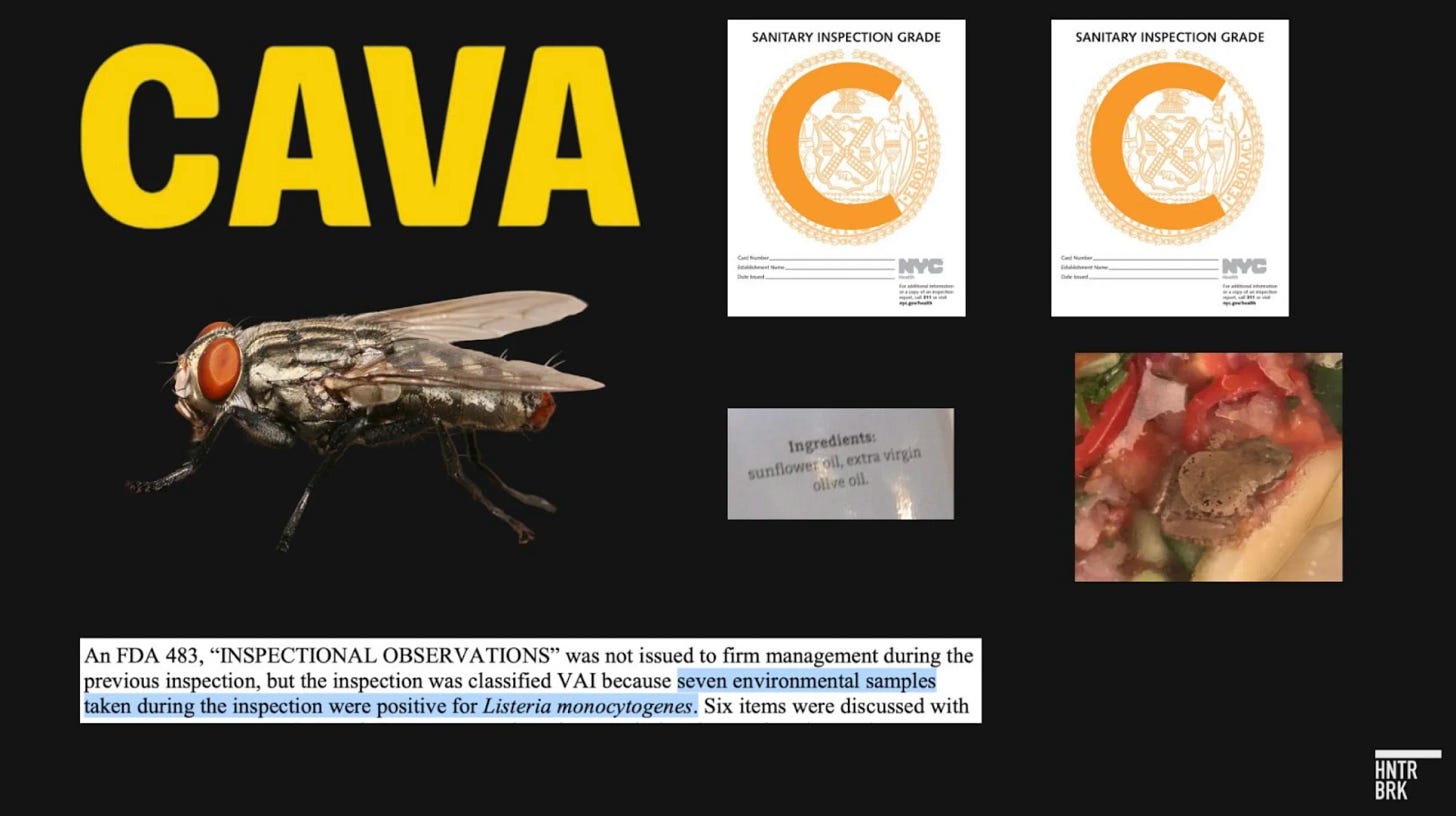

The Cava (NYSE: $CAVA) on Wall Street, located minutes from the Charging Bull, received a “C” grade from the New York City Department of Health.

The range of potential pests that inspectors identified on the premises reads like something out of the Old Testament — filth flies, blow flies, flesh flies.

The health inspection report also identified improper food storage and protection protocols, inadequate temperature control for hot foods, unsanitary food contact surfaces, and issues with drainage and waste disposal.

The Wall Street location of the rapidly expanding Mediterranean fast-casual chain, whose menu emphasizes fresh, healthy ingredients, was also briefly shut down after failing to properly display its grade to the public — relatable content for any kid who has hidden a report card from their parents.

A couple miles uptown, Cava’s East Village location also has a “C” rating — and a pest problem of its own. At this spot, it was docked because its eggs were kept insufficiently cold, the hot dishes were kept insufficiently hot, food preparation surfaces were not adequately cleaned, and there were issues with the hand-washing facilities.

“It’s important to realize that these inspections deal with more than just sanitation,” Donald Schaffner, the chair of the food science department at Rutgers University, told Hunterbrook Media over email. “The whole reason why we have restaurant inspections is that when violations like those that are seen here occur, this increases the risk of patrons getting food poisoning.”

“The more violations a restaurant has, the more likely it will be that eventually they will make someone sick,” he added.

Now, as any viewer of The Bear knows, the doling out of restaurant sanitation grades can seem heavy-handed. But Cava’s consistently poor marks leap out.

A 2024 analysis found 86.9% of New York City restaurants have “A” grades. And Hunterbrook’s review of the New York sanitation website found that just 3.48% of evaluated restaurants across the five boroughs have a “C” grade.

Meanwhile, 18% of Cava’s 11 New York locations with a rating have a “C.” That’s over five times more than would be expected if the average Cava were as clean as the average restaurant. (Two Cava restaurants in Gotham have yet to be graded.)

No other major fast food chain looked at by Hunterbrook comes close to Cava’s checkered sanitation record in New York City.

Take McDonald’s, for example, which has 173 Big Apple locations that are rated, 170 of which enjoy an “A” rating.

Sweetgreen, one of Cava’s biggest competitors, has 36 New York City locations that are rated — and 36 “A” grades.

And Chipotle, a chain with a long history of food safety issues, doesn’t have a single location in New York City with a “C” rating. (Of its 112 rated restaurants, 107 have “A” grades and two have “B” grades, with three others pending.)

Since receiving these grades, Cava Group Inc. told Hunterbrook, the company has “brought in new leaders and added quality assurance resources, including a full-time team member dedicated solely to our restaurants in the Northeast,” adding that its most recent inspections have resulted in “A” grades. “We’re eagerly awaiting the next cycle of inspections.”

Some think a nearly $15 billion company’s growing pains are no excuse for causing stomach pains.

Dan Geneen — a comedian and former award-winning food video producer for the popular outlet Eater— said Cava’s grades would be forgivable for a “non-chain” restaurant, claiming the rating system has many arbitrary pitfalls.

But for “as big a corporation as Cava,” he said, “however you feel about the rating system, you can nearly ensure success by hiring consultants and doing trainings; for them not to be on top of it, as evidenced by TWO C’s, it makes me think: What other corners are they cutting?”

And Cava really is big — and growing, fast, with a target of 1,000 locations by 2032 and a soaring stock price.

Simon Kim, who owns Cote and Coqodaq — two of New York City’s most exclusive restaurants, known for the Butcher’s Feast and caviar chicken nuggets — shared a similar perspective with Hunterbrook. “Personally, I take big risks,” he said, “cause I have a stomach of steel.”

But while he is fine with repeated “trips to the bathroom” for a transcendent meal, he said a lunch bowl wouldn’t bring him enough “euphoria” to risk it.

“More concerning than the ‘C’ itself is the complacency,” Kim said. “You have more money than the world. Your stock price is skyrocketing. Why aren’t you fixing that?”

“It almost feels like corporate arrogance.”

It’s not only Cava’s New York City locations that have raised food safety red flags.

The FDA’s files on Cava, which Hunterbrook received through a Freedom of Information Act request, reveal a history of questionable food safety practices — though there is no indication in the documents that the facilities have ever been sanctioned or shut down by the agency.

From 2017 to 2022, the inspections of Cava facilities featured in the documents found repeated failures to implement comprehensive hazard controls, particularly around allergen management, metal contamination, and sanitation verification.

Poor food safety can be a harbinger of E. coli, salmonella, norovirus, campylobacteriosis, and Staphylococcus aureus infections, according to several professors of food science who spoke to Hunterbrook.

Lee-Ann Jaykus, professor emerita of food, bioprocessing, and nutrition sciences at NC State University, shared her perspective on why Cava may be receiving a disproportionate number of food safety violations at Cava chains. “There’s a term that is used a lot in my field now which is called a culture of food safety. And basically what it means is that the company values food safety, values the rules that are out there to keep food safe,” she said.

“The fact that you’re seeing this amongst many Cava establishments would suggest that they don’t have some kind of standardized food safety program that they’re implementing,” she added. “It doesn’t look like they have a very strong culture of food safety.”

In a comment to Hunterbrook, Cava shared its perspective that “food safety is paramount to what we do,” adding that it is “embedded in our culture, our policies, and our practices.” The company cited its food safety and quality assurance team which “establishes and monitors our food safety programs and protocols and ensures that our restaurants, team members, production facilities, and vendors and suppliers meet our standards.”

Cava also stated that they train “team members in food quality and safety, with continuing education throughout the year, and regularly work with outside food safety experts.”

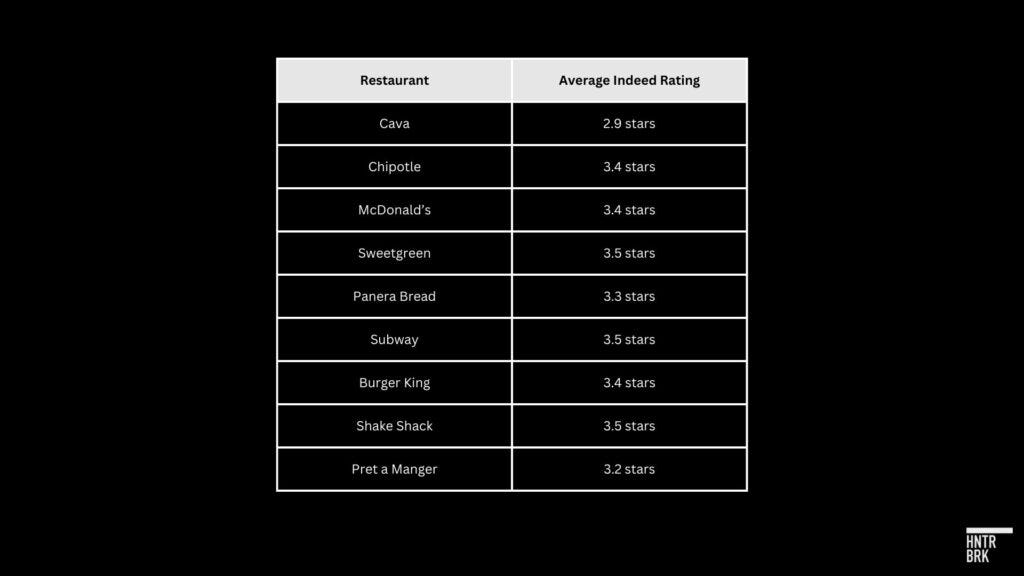

A Hunterbrook analysis of reviews from Indeed.com, a hiring platform that aggregates employee reviews, showed that Cava employees are, on average, less satisfied with their workplace than their counterparts at chains such as Sweetgreen, Subway, Chipotle, McDonald’s, Panera Bread, Burger King, Shake Shack, and Pret a Manger.

And while at least one reviewer said there were “good safety and food safety protocols” at the Cava where they worked, many of the reviews that mentioned “safety” were less kind. (This is, in fairness, unsurprising: How many people are going to go online and anonymously compliment the hygiene of their workplace?)

“No knowledge of food safety,” said one of the reviewers, who claimed to have worked as a Cava grill cook. “FOOD SAFETY is not met here,” read another, by someone who claimed to have been a culinary lead.

A reviewer who claimed to have been a special operation trainer was even harsher. “The food safety standards are awful,” they wrote. “We were forced to serve expired greens, slimey [sic] cucumber tomato, and the meat was rarely fresh.”

(At other times, Cava’s meat has been a little too fresh: A customer once found a live frog hopping among the tomatoes and tzatziki in her salad.)

As Cava’s rank-and-file employees dish on the restaurant’s safety protocols online, its executives and largest shareholders have been upchucking the stock. In the last six months, company insiders — including Chief Executive Officer Brett Schulman, Chief Financial Officer Patricia Tolivar, and multiple board members — have unloaded shares now worth more than $1.6 billion, according to Yahoo Finance’s tracker.

Ronald Shaisch, the legendary food entrepreneur who founded Panera Bread and became a billionaire from his investment in Cava, has sold more than $300 million worth since June.

Cava told Hunterbrook “this kind of activity is natural and expected when a business and a stock perform as ours has since the IPO,” adding that many of its investors have “held positions in the company for nearly a decade and continue to support us.”

Cava: The Next Chipotle?

For years, Cava has been referred to as “the next Chipotle.” And there is merit to the comparison with the remarkable growth of the Mexican fast-casual chain.

As Chipotle did when it launched, Cava offers the fast-casual sector something exciting: seemingly healthy and highly customizable meals at prices that are similar to competitors like Sweetgreen. It’s also pretty delicious. People really do go crazy for the Crazy Feta.

And the company has been taking off, especially since its acquisition of Zoe’s Kitchen in 2018, which accelerated the pace of its expansion efforts. In 2023, Cava opened 72 new restaurants, growing its footprint to more than 300 nationwide.

Last quarter, Cava’s net sales grew by 35% to more than $230 million — while its traffic increased by about 10 percent, according to a CNBC write up that characterized these results as especially meaningful because, during the same period, “many other restaurant companies have reported declines in visits as consumers pull back their spending.”

This growth seems to have fired up investors, sending Cava’s stock price soaring by more than 400% since its executives rang the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange during its IPO last June, blocks away from the ill-fated Wall Street location.

And investors seem to be predicting this growth will continue. As of this month, Cava is trading at around 334 times trailing twelve-month earnings through June 2024, according to Hunterbrook’s analysis. For comparison: Shake Shack trades at 163 times earnings; Chipotle trades at 62 times earnings; and Starbucks trades at 22 times earnings.

Cava’s higher ratio than the other restaurant businesses analyzed by Hunterbrook holds true when looking at its December 2025 consensus earnings estimates.

Cava’s price-to-earnings ratio is notably better than Sweetgreen’s, which is null, because its earnings are negative — and Cava has penetrated way fewer markets than behemoths like McDonald’s and Domino’s, so it’s not unreasonable to expect it may have more room to grow as well.

Lauren Balik, a data scientist and owner of Upright Analytics known for her colorful, provocative, sometimes outrageous hot takes on X (née Twitter), has said food safety issues may be the flip side of the company’s rapid expansion efforts.

Cava is the “next Chipotle,” she wrote on the blogging platform Medium in January. “But it’s the Chipotle of 2015.”

She was referring to Chipotle’s massive drop in stock price (around 40%) after a series of food poisoning outbreaks in the 2010s.

It ultimately took years for the Mexican chain to recover financially. “I’m betting on a Cava health crisis in 2024,” wrote Balik, who disclosed that she was short Cava stock in her January essay.

Despite what appears to have been a very bad trade — Cava is up more than 150% since Balik’s piece — Balik doesn’t seem to be giving up. “Most of the food poisoning that happens attributed to leafy greens happens in October,” she said in an interview with Hunterbrook, citing a CDC paper.

Balik said she made her short position bigger recently — though it remains a small part of her portfolio.

Online Reports of Diarrhea, Vomiting, Food Poisoning — As FOIA Records Reveal Questionable Production Facilities

It was definitely something he ate.

“At first my stomach just hurt a ton,” Mason said, explaining how he went from eating a Cava bowl to being glued to the toilet bowl.

Mason and his wife Alice, who asked Hunterbrook to withhold their last names, live in Virginia, and he said he was a regular at Cava’s Fairfax location — that is, until he allegedly got food poisoning. He was such a fan, in fact, that Alice had bought him a lamb and basmati bowl from Cava as a little treat, a thank you meal for helping her and her mom with a project earlier that day.

“It was hard to even focus on breathing. I got severe diarrhea and pretty aggressive vomiting all throughout the night,” Mason told Hunterbrook. “My stomach felt like I was being stabbed and someone was twisting the knife. I’m not exaggerating when I say that was the worst stomach pain I’ve ever had.”

“He was having trouble even talking,” Alice added. “Eventually it got to a point — sorry, this is graphic — where I had to clean up his vomit that was in the bathtub because he couldn’t control how fast it was coming up.”

Alice said she submitted a complaint to the Fairfax County Health Department, and although she claims to have gotten a response saying that the agency had assigned someone to the case, she said she never heard back from them.

Mason is one of many people on social media who claim that eating at Cava made them very, very sick — with people complaining about everything from throwing up “a shid ton” to being “barely” able to “stomach food” and having “diarrhea.”

“As is the case for virtually every restaurant company, we get reports of illness from time to time,” Cava said in its statement to Hunterbrook. “When we hear from or see an online post from a guest who’s been sick, we take it seriously and investigate complaints. Since our founding, we have served more than 200 million guests.”

The FDA documents Hunterbrook acquired through the Freedom of Information Act suggest that, like some of its restaurant locations, Cava’s production facilities have drawn negative attention from health inspectors.

In a 2017 inspection, the FDA raised several issues with Cava management.

The agency cited the company for not conducting a proper analysis that accounted for a multitude of possible biological hazards in ingredient storage, refrigerated processing, and packaging, specifically noting that the firm did not perform an “ingredient hazard analysis.”

The FDA also said Cava failed to document which steps in the production process could introduce pathogens such as Listeria, one of the most common causes of food poisoning. The report highlighted the absence of critical preventive controls for metal contamination as well, stating there was “no metal detector preventive control” for bulk bags of products like hummus.

At the inspection, the FDA collected 119 swabs to analyze them for the presence of Listeria.

In a follow-up inspection report from a December 2017 visit to the facility, the FDA wrote that “seven environmental samples taken” during the first inspection “were positive for Listeria monocytogenes.”

Cava made “voluntary” corrective measures and by the time of a 2022 FDA inspection, many of the problems had seemingly been addressed. Some concerns remained, however, including Cava’s failure to provide documentation “disclosing products manufactured by your firm which include, but are not limited to tzatziki and traditional hummus have not been processed to control for biohazards.”

In its statement to Hunterbrook, Cava noted that “in the seven years since the March 2017 FDA inspection, we have heavily invested in and materially improved our processes, including making many changes shortly after the inspection.” The company said these changes include “cold pasteurization,” installing “equipment that helps us identify and prevent foreign material — like metal — in our products.”

Cava also noted “all 11 Maryland Department of Health inspections since 2018 resulted in Substantial Compliance.” In 2023, about a month after Cava debuted on the New York Stock Exchange, the company had to issue a recall of its prepackaged spicy hummus, according to a company press release, “due to the potential for the product to contain undeclared sesame, which is a food allergen.”1

Cava’s Strange, and Sometimes Deceptive, Marketing

To its credit, Cava doesn’t hide the fact that it could give you a case of the runs.

In 2023, as Balik noted in her blog post, Cava distributed bumper stickers to promote its signature Crazy Feta dip. They read: “I AM LACTOSE INTOLERANT BUT I EAT CRAZY FETA.”

Most restaurants wouldn’t have the intestinal fortitude to intentionally evoke diarrhea in their marketing, but Cava is on a roll. The company’s valuation has multiplied since this innovative campaign, which was, perhaps, refreshingly honest to consumers.

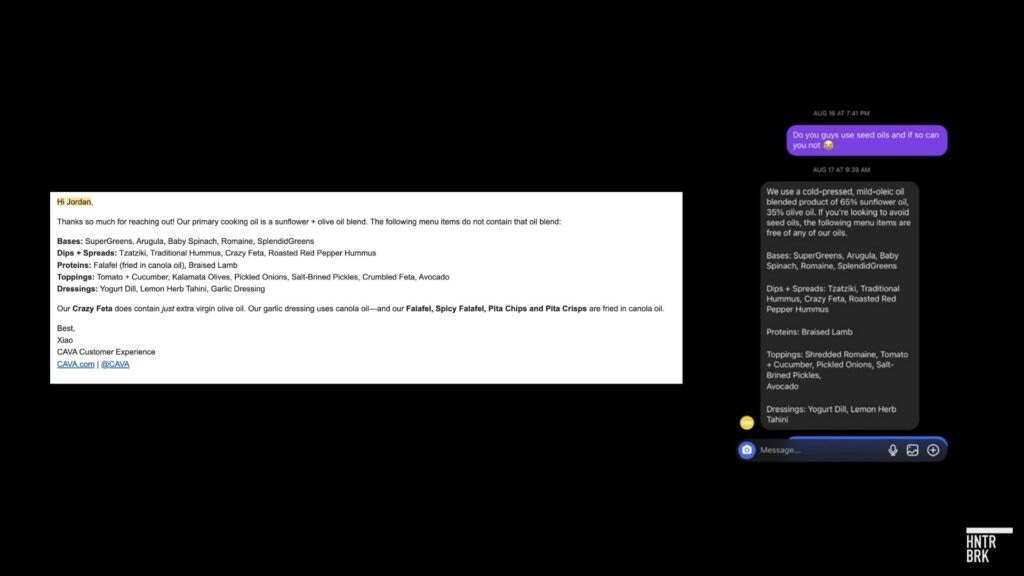

Cava’s branding seems somewhat less forthcoming about cooking oil. Its website claims it uses an “olive oil sommelier” as its supplier. “We’re Greek, so olive oil isn’t just a cooking staple — it’s a way of life,” the company wrote on Instagram.

But when a health influencer who uses the handle @santacruzmedicinals investigated Cava’s olive oil, he found that the company actually uses a sunflower seed-olive oil blend to prepare its food, which contains more sunflower than olive.

In response to Hunterbrook’s questions on this, Cava said that it has used “nearly 200,000 gallons of olive oil in our products” in the last 12 months, but shared that it does use a blend of sunflower oil and olive oil in “several menu items.”

“Our sunflower oil is a high-quality, cold-pressed oil and is sourced from the same supplier in Greece as our olive oil,” the company added.

The app Seed Oil Scout — which tracks what restaurants do and do not use seed oils — showed Hunterbrook an email from Cava’s Customer Experience team that stated the sunflower and olive oil blend is its “primary cooking oil,” noting that its “Falafel, Spicy Falafel, Pita Chips and Pita Crisps are fried in canola oil.” (The Crazy Feta, however, contains “just extra virgin olive oil.”)2

That olive oil/sunflower mixup may not sound like a big deal to you and me, but it is to the growing community of people who believe that seed oils — which can be derived from sunflowers, soy, and more — are bad for your health. The community is so passionate that, weeks ago, Donald Trump was asked if he would ban seed oils altogether as president.

The olive-oil-sunflower-oil-bait-and-switch hit home for one of the authors of this article, whose sunflower seed intolerant boyfriend once fell ill after eating Cava. He also ate Cava’s pita bread that day, which may have exacerbated his illness due to an ingredient to which he is also allergic: flax seed. (He learned about the flax only after exchanging emails with the company.)

He no longer patronizes Cava, but the chain’s sanitation record doesn’t appear to be a deterrent to others.

Last week, the Cava on Wall Street was jam-packed during lunch. One customer told Hunterbrook they didn’t understand what the “C” grade meant (try that one on your parents, kids). Another admitted it’s “not unimportant,” but “I’m starving.”

A diner named Jose Vargas was less friendly. “It’s embarrassing,” he told Hunterbrook. “A ‘C’ is crazy. I didn’t even notice that. Everybody should care. A ‘B’ is understandable, but a ‘C’ is too much.”

Many of the diners we spoke to had no idea they were eating at a “C” restaurant until asked about it.

“You just ruined my lunch,” a man named Tim said.

Eve Peyser writes about the weirdest, funniest, and most interesting aspects of modern life. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, GQ, and many other publications.

Michelle Cera is a sociologist specializing in digital ethnography and pedagogy. She is a Ph.D. Candidate in Sociology from New York University, building on her Bachelor of Arts degree with Highest Honors from the University of California, Berkeley. Currently serving as a Workshop Coordinator at NYU’s Anthropology and Sociology Departments, Michelle fosters interdisciplinary collaboration and advances innovative research methodologies.

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life.

***

Jim Impoco is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek who returned the publication to print in 2014. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has a Master’s in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work opportunities, and press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2024 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.

Undeclared Sesame is not a bad band name.

Sam, one of the authors of this article, was once offered equity in Seed Oil Scout. He did not fill out the form to accept. This was likely a bad financial decision.[