RadNet: The AI Story That Doesn’t Add Up

Wall Street keeps asking if there’s an AI bubble. The answer seems obvious once you move past the usual suspects.

By: Bethany McLean, Andrew Ford, Laura Wadsten

Editor: Jim Impoco

Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is short RadNet (NASDAQ: $RDNT) at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. See full disclosures on our website.

RadNet’s much-hyped AI business is a sideshow. Less than 5% of the medical imaging company’s revenue — about $65 million out of $1.5 billion in the first nine months of 2025 — comes from its newfangled Digital Health division. Much of that division’s revenue, and two-thirds of its reported revenue growth excluding recent acquisitions, comes from selling software to RadNet’s own imaging centers. RadNet also charges mammogram patients $40 for an “AI read” using technology that experts say is commoditized. And yet, the company’s stock has soared in value since its AI rebrand, trading at a much higher multiple than historic norms and competitors.

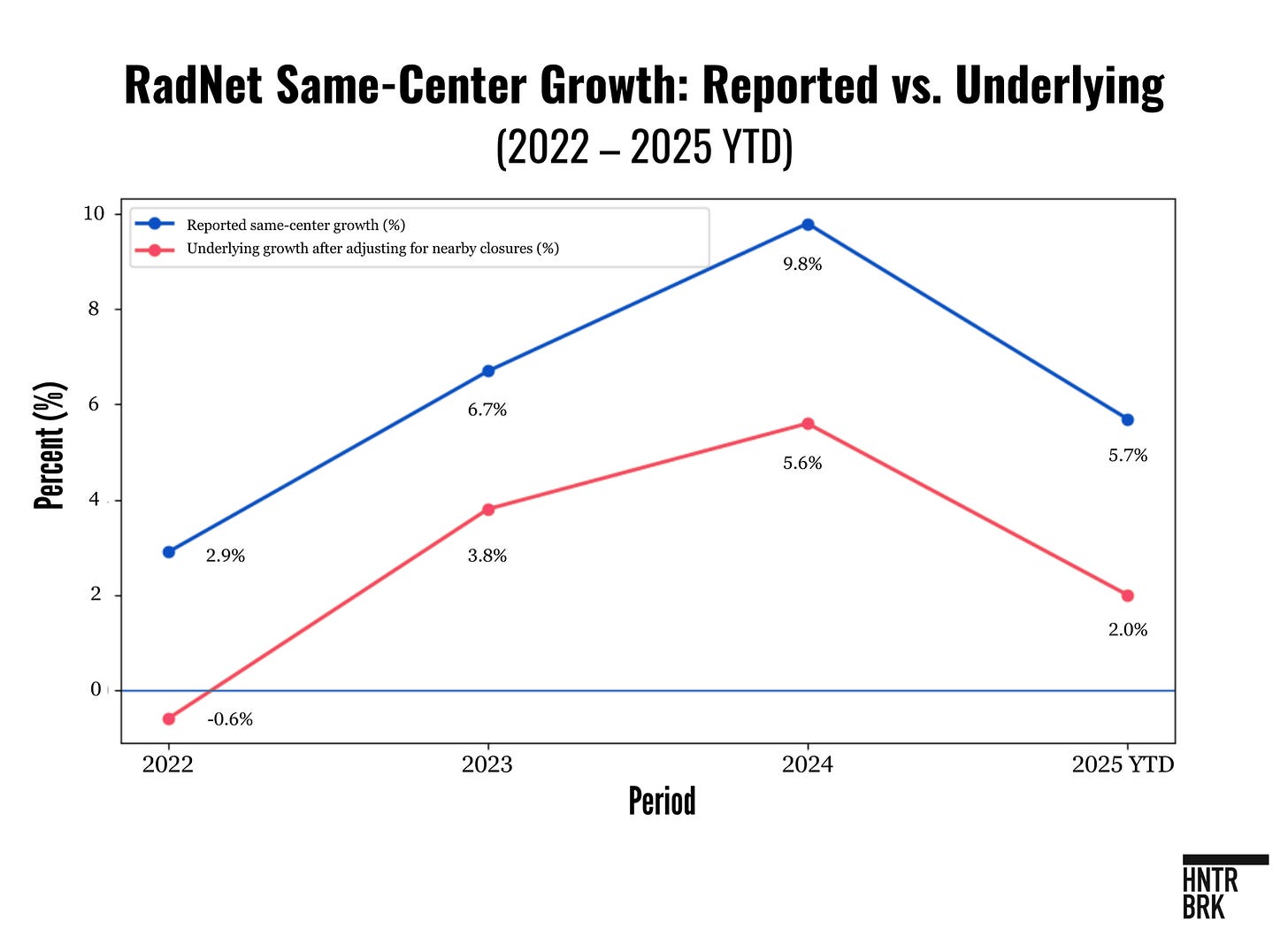

The success of RadNet’s roll up business is also misunderstood. By reconstructing RadNet’s footprint and tracking closures, a financial analysis estimates that about half of reported “same-center” revenue growth in recent years came from closing centers located within 15 minutes of surviving RadNet sites and apparently shifting the patients over. Get rid of this consolidation, and organic growth drops to an estimated 2.5%–3%, rather than the reported 6%–10%.

The truth is buried beneath inconsistent disclosures. RadNet’s 2024 10-K filing said it opened 44 centers through internal development; its earnings release said nine. One 10-Q filing reported 398 centers in operation; a later filing restated that to 375 for the same period, with no explanation. Even the online “center locator” shows seven or eight fewer locations than the headline count. These inconsistencies make it difficult to track how the footprint is actually changing amid purported same-center sales growth.

Manufactured profits. RadNet’s soaring stock relies on adjusted margins that strip out both stock-based compensation and some R&D spending, which is a critical variable in assessing the profitability of a tech business. After backing out those accounting techniques, RadNet’s operating margins are actually down, not growing.

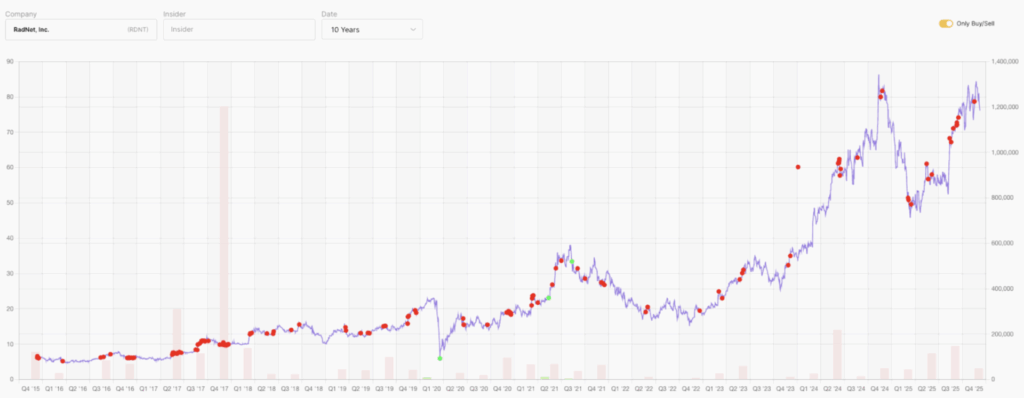

Insiders are cashing out. Over the past two years, RadNet insiders have sold more than 780,000 shares — worth $50.9 million — without any open-market purchases.

RadNet did not respond to repeated requests for comment. Hunterbrook repeatedly sought RadNet’s side of the story, but the company did not engage.

Wall Street keeps asking if there’s an AI bubble. The answer seems obvious once you move past the usual suspects.

Sure, the headline numbers are staggering: $4 trillion in projected spending through 2030, with hyperscalers like Nvidia, OpenAI, and Google announcing new deals seemingly weekly. But the tech giants aren’t the only tell.

It’s the smaller companies slapping “AI” on their pitch decks and watching their valuations soar.

Just as in the dot-com boom when Zapata, a fish company, renamed itself zap.com and saw its stock double, companies are making a fortune in this frothy market by tying themselves to AI — at least in investors’ minds.

If the label is just a label, the stock may turn out to be fish food.

Consider RadNet ($RDNT), a nearly 50-year-old radiology chain pulling off one of the most audacious AI rebrandings in recent memory.

For decades, RadNet basically just ran imaging centers — brick-and-mortar clinics offering outpatient services like mammograms, CT scans, X-rays, and prostate cancer screenings. Until 2020, the stock traded at less than $15 a share.

Then its management team launched a rebrand, now positioning the company as “the leader in the development of artificial intelligence for mammography, ultrasound, and x-ray.”

Wall Street has eaten it up. RadNet’s stock has soared as high as $86, reaching a market capitalization of more than $6 billion — about three times its sales this past year. That’s an aggressive valuation for what remains, at its core, a low-margin, imaging center roll-up, with more than 400 centers across eight states.

Over several months, Hunterbrook investigated RadNet’s AI pivot — reporting from imaging centers in Phoenix to the industry’s flagship conference in Chicago, interviewing more than a dozen radiologists and sector executives, and reconstructing the company’s shifting footprint through archived data and SEC filings. What emerged was a gap between story and substance: a Digital Health business that generates much of its growth by invoicing a different RadNet business line; a same-center sales metric seemingly juiced by undisclosed consolidations; financial disclosures that don’t add up; and insiders using the stock run-up to cash out.

Hunterbrook has reached out to RadNet repeatedly to hear the company’s perspective on our findings. RadNet has not replied to any of these messages or calls.

Slouching Toward Artificial Intelligence

At the heart of RadNet’s metamorphosis is Enhanced Breast Cancer Detection — AI-powered technology the company markets as “a more accurate mammogram.” RadNet integrated EBCD with another product it acquired named DeepHealthOS, a platform it describes in a buzzword-laden blur as a “pioneering cloud-native operating system powered by clinical AI that improves disease detection and that leverages operational generative AI.”

The two acquisitions, along with a legacy software business and assets from several other recent purchases, make up the division RadNet is highlighting to investors as part of the AI boom: Digital Health.

On paper, the pivot looks brilliant. When RadNet announced its second-quarter earnings in August, it reported that revenue in its Digital Health segment grew 30% year over year, and that its profitability margin had improved. Over the next month, the stock climbed some 40%.

“We hope, and we aspire to grow our Digital Health software business in the range of 30% per year for many years to come,” CFO Mark Stolper promised on the earnings call. The third-quarter results, announced in November, looked even better, with Digital Health revenue up 52%.

Yet, strip away the glossy Digital Health chrome and the AI spin looks more like hype than reality. The disconnect between the AI-fueled valuation and the reality on the ground — in the reading room — is jarring.

“Every AI company is knocking at your door,” said Dr. Roman Keller, a radiologist at an independent practice in Minnesota. “They want to sell you something, but what is it really going to give us?” That sentiment was echoed by a range of radiologists and industry experts Hunterbrook spoke with for this investigation.

Are radiologists biased against their obsolescence? Maybe. But even Andrej Karpathy, one of the founders of OpenAI — who ran AI at Tesla as well — posted to X in September about the slow pace of artificial intelligence’s encroachment on radiology. “The benchmarks are nowhere near broad enough to reflect actual, real scenarios,” he wrote, claiming radiology is “too multi-faceted, too high risk, too regulated” for AI to replace many jobs.

RadNet’s AI offering is also, financially speaking, a rounding error. Even in the company’s published numbers, less than 5% of its revenue is coming from Digital Health.

The source of that revenue should be alarming. Most of RadNet’s recent growth in this business appears to come from sales to its own imaging centers, a fact that is buried in complicated intercompany transaction disclosures.

Beneath the tech patina, RadNet looks like an ordinary business — one whose financial metrics, including reported same-center sales, raise questions of their own. One example: same-center sales.

Wall Street sell-side analysts have pointed to the company’s same-center sales growth at its imaging centers as a reason for their bullishness on the stock; the numbers, as presented, also look like evidence of AI-driven efficiencies.

Yet relying on that metric requires trusting that the denominator — that is, the number of stores RadNet purports to operate — remains easy to track over time. A detailed investigation of the company’s footprint suggests the reality is more complicated. That’s because RadNet has been essentially merging separate, nearby locations into single reporting units. Hunterbrook’s analysis, conducted with the help of outside financial analysts, suggests this maneuver may have artificially more than doubled RadNet’s apparent same-center sales growth.

Stack the AI hyperbole against the slippery metrics of the core business, and a key question remains: Other than an old school radiology business, what, exactly, is real about RadNet?

The Brutal Economics of Imaging Centers

RadNet needed a new story to boost its sagging stock.

Its core business, running imaging centers, was once highly profitable, thanks in large part to generous Medicare reimbursement rates.

That drew new entrants, including RadNet itself. Its CEO, Dr. Howard Berger — a physician by training — founded RadNet in the early 1980s with a group of other doctors as a single Los Angeles imaging center. Over time, RadNet morphed into a roll-up play, buying other imaging centers, with the idea that consolidation would bring efficiencies and growth.

But in the early 2000s, the economics of the business became harder.

The 2005 Deficit Reduction Act slashed Medicare reimbursement rates, especially for MRIs and CT scans — both of which are core to RadNet’s business. Since then, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS, which sets how much the government will pay for healthcare services, has cut imaging reimbursement rates further, and because commercial payers benchmark to Medicare, most reimbursement is declining in this area.

It’s become a vicious spiral, at least from the standpoint of healthcare providers.

As technology has improved, providers have gotten more efficient — only to see the government strip away their hard-won gains. For example, in the 2026 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposal, the CMS applied a 2.5% “efficiency adjustment” cut specifically because delivery had improved.

Facing a tough market and shrinking margins, RadNet pivoted around the start of this decade, buying a string of small AI companies. The acquisitions included companies like Aidence, which specialized in AI-enabled detection for lung cancer; Quantib, which used AI for prostate and brain screenings; and DeepHealth, an AI and machine learning company.

In 2023, RadNet unveiled a new version of DeepHealth at the Radiological Society of North America’s annual meeting in Chicago. It was “designed to dramatically drive efficiency and transform radiology’s role in healthcare,” said a company press release. The pitch was simple: AI-enabled apps would help everyone in the imaging business better manage the delivery of care. Although the details were vague, the company claimed 300 external customers were already using DeepHealth.

RadNet has since doubled down on its acquisition strategy. Earlier this year it paid about $100 million — five times the company’s revenues — for iCAD, a leading provider of breast-imaging software whose FDA-cleared product, ProFound AI, helps radiologists read mammograms.

The buying spree helps make RadNet look like a rocket poised for the stratosphere. Up close on the launchpad, however, the engines seem to be barely sputtering.

A Crowded, Skeptical Market

In late November, thousands of doctors traveled to Chicago’s McCormick Place for this year’s meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, or RSNA. Their name tags, which highlighted their academic training, stood in sharp contrast to the massive LED displays and the showmanship of the companies marketing their wares to the doctors.

Back in 2016, the British-Canadian computer scientist Geoffrey Hinton said that “people should stop training radiologists now,” because AI was going to replace them.

Radiologists are still around in large numbers, as shown by the turnout in Chicago. But Wall Street keeps betting AI will reshape the industry, and companies have been happy to oblige — AI was everywhere at the RSNA conference, in the booths of the exhibitors and throughout the sessions.

“I think we’re in a time of extraordinary growth and opportunity,” said Dr. Shlomit Goldberg-Stein, director of AI at Northwell Health Radiology.

Others were more pragmatic, if not skeptical, about AI’s value. One expert compared AI to the passing fad of cloud offerings that took over the RSNA a few years ago.

“There are these sort of noms du jour that get used,” said Julian Marshall, a consultant on breast imaging and AI. “But ideas are a dime a dozen,” he added.

RadNet’s Chicago booth, bathed in lavender lights with a purple banner that read, “Unifying the Imaging Experience,” wasn’t the only one hawking AI solutions.

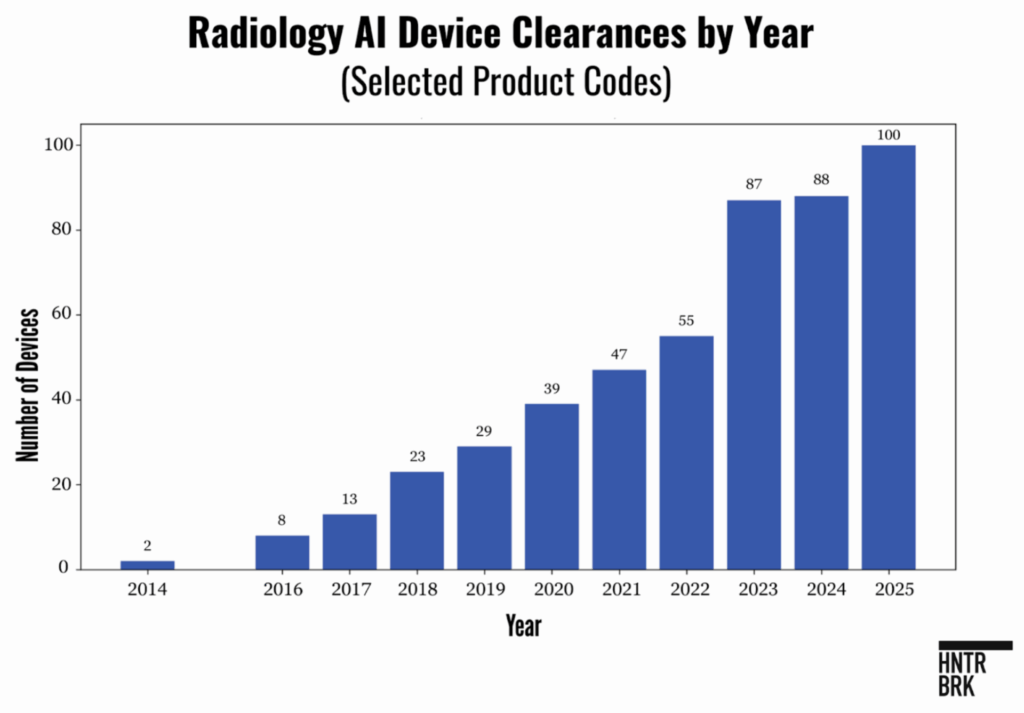

In a crowded field, RadNet’s technology doesn’t seem to stand out. Regulatory hurdles are not a moat, either: New AI-enabled medical device authorizations in radiology have nearly quadrupled since 2019.

RadNet’s “AI read” service — which allows patients to pay $40 for an AI second opinion on their mammograms — seems especially commoditized. SimonMed, a RadNet competitor that has 160 imaging centers across the country, just rolled out a “personalized” version of similar technology called Mammogram+, for which they charge an extra $50.

The mounting competition makes finding customers, and securing government and private insurance reimbursement, challenging. Even RadNet’s signature acquisition, iCAD, which by its own account held nearly 50% of the AI breast cancer detection market, generated only $20 million in revenue the year before it was acquired. Investors showed little enthusiasm for the standalone business: iCAD’s stock hovered around $2, for a market capitalization of about $50 million, though RadNet ultimately paid $100 million.

Because insurance generally doesn’t cover this upsell, women are voting with their wallets — and the percentage of mammography patients at RadNet centers where the AI read is offered who opt in has seemingly stalled at less than 50%. RadNet, meanwhile, has cut prices by about one-third, to $40 from $60 in some areas of the country.

The corporate market, meanwhile, has been cool to Digital Health’s pitch.

On its earnings call in March 2024, the company said DeepHealth’s tools would be “incorporated into the RadNet workflow by year end” and then licensed to external customers by 2025. In August, the story changed: RadNet shared it was still testing DeepHealth, and that the service was not fully rolled out even in its own imaging centers. “So nobody is using the full range of the potential of the DeepHealth in the outpatient space, even in RadNet at this point in time,” said Berger on the earnings call.

RadNet has announced one big new external customer: In November 2024, ONRAD, which provides radiology services to hospitals, said it would license DeepHealth, but it’s not clear how much revenue is tied to that contract. At the RSNA conference, RadNet and GE both talked up a letter of intent to collaborate on distributing AI tools, but evidence of impact from that deal is scant, too.

With a dearth of external customers, RadNet’s best customer for Digital Health has apparently been itself.

Following a 2024 reorganization, RadNet shifted an older technology called eRad from its core Imaging Center business to its Digital Health business, instantly boosting the new unit’s size. In the first three quarters of 2025, RadNet’s sales of Digital Health products and services to its own Imaging Center unit grew about 47% versus the previous year. Those sales now account for roughly half of Digital Health’s total revenues — and more importantly, two-thirds of the business’s year-over-year growth, excluding the impact of recent acquisitions. True third-party sales, dominated by legacy software, are still growing, but the trajectory is erratic.

When part of a company’s business consists of sales from one division to another, the bookkeeping should be simple. It is revenue for the seller and a cost for the buyer. In RadNet’s case, if its Digital Health unit sells software to its Imaging Center unit, that sale should count as revenue for Digital Health — and as an expense for the Imaging Center unit.

In its most recent 10-Q, RadNet said Imaging Center revenue “includes intersegment revenue.” Yet elsewhere, the company suggests the opposite: that Digital Health revenue does include those internal dollars. It’s hard to see how both can be true.

This may sound technical, but it matters to investors attempting to value the company. Because if internal sales are not cleanly treated as expenses at the Imaging Centers, this math can artificially boost Imaging Center EBITDA margins. In other words, manufactured operating leverage.

Of course, the real question is why RadNet is so reliant on intercompany sales in the first place.

One answer is that competitors are understandably wary of handing revenue — and potentially data — to a direct rival.

That friction played out in real time after the iCAD acquisition. Before the deal, iCAD counted SimonMed, one of the country’s largest imaging chains, which now sells Mammogram+, as a critical customer. Yet almost immediately after RadNet announced the buyout, SimonMed signed on with a different provider, Lunit. The message was clear: RadNet’s potential customers for its DeepHealth business view the company as a predator, not a partner.

“They compete with the radiologists they want to sell the AI to,” said Marshall, the imaging consultant at the RSNA annual meeting.

“The problem is many places think of RadNet as almost like a predatory company,” the chief innovation officer of a RadNet competitor said. “You don’t want to let a potentially contract-stealing vendor into your space, that’s the point, even if it’s just the software.”

“No one buys it because they’re a competitor,” added Craig Hadfield, the CEO at Lunit, in an interview with Hunterbrook at RSNA. He said that RadNet’s attempts to sell DeepHealth to other companies have been “very unsuccessful.”

Numbers That Don’t Add Up

Without the AI hype, RadNet is just a brick-and-mortar imaging business — with accounting questions of its own.

This includes a key number: same-center sales.

Analysts cite RadNet’s strong same-center sales growth — 9.8% in 2024, according to the company’s 10-K — as a reason to believe in the company’s narrative of AI-driven efficiency. For outsiders, it’s proof of RadNet’s special sauce. “The strong volume results … reinforce the impact DeepHealth is having on the core imaging business,” wrote Barclays’ Andrew Mok in a recent sell-side note.

Same-store sales calculations are inherently messy. RadNet, for example, is constantly closing centers as well as opening new ones, both via acquisitions and from scratch. To filter out the noise, RadNet says its same-center calculation excludes all centers that were opened, acquired, sold, or closed in the comparison period.

In other words, same-center revenue growth should track only those locations open for the full duration.

RadNet doesn’t release the underlying figures. Instead, it reports the number of centers it owns and operates at the end of the quarter, plus a tally of additions and disposals.

But the numbers jump around. For instance, in its 2024 10-K filing, RadNet says it opened 44 new centers via internal development. But in the earnings release, Berger pointed to nine new openings during the year. Another section of the 2024 10-K says they added 63 centers via acquisitions in the past three years, but the table shows only 46. RadNet’s 10-Q filed for the first half of 2025 lists the previous year’s center count as 375. But the 10-Q filed back then reported 398 centers — in other words, 23 centers simply vanished.

The discrepancies prompted us to take a closer look.

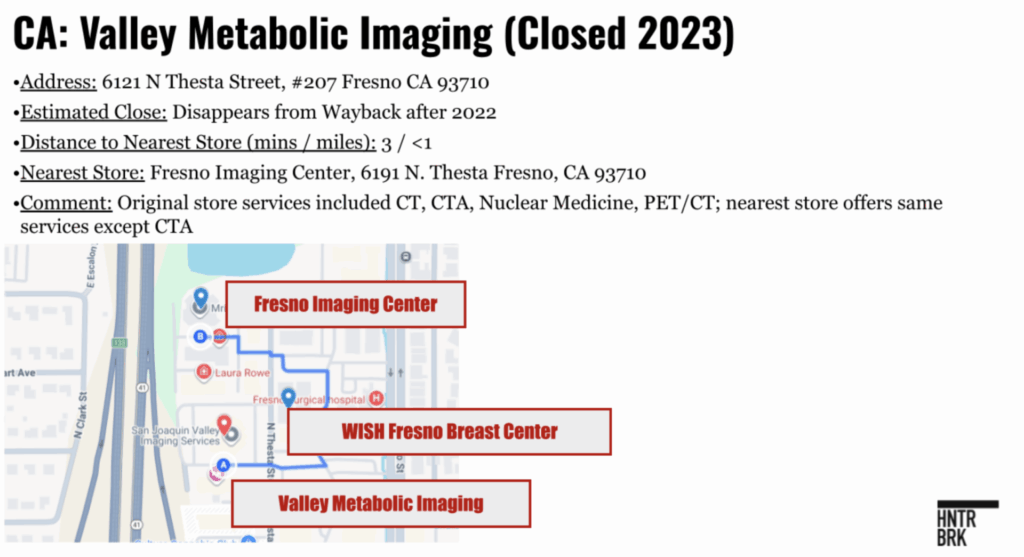

One California center, called Valley Metabolic Imaging, disappeared from RadNet’s website by 2023, but it’s actually just a three-minute walk from the existing Fresno Imaging Center, also owned by RadNet, offering nearly identical services.

So was the center truly closed, or just consolidated into the Fresno site?

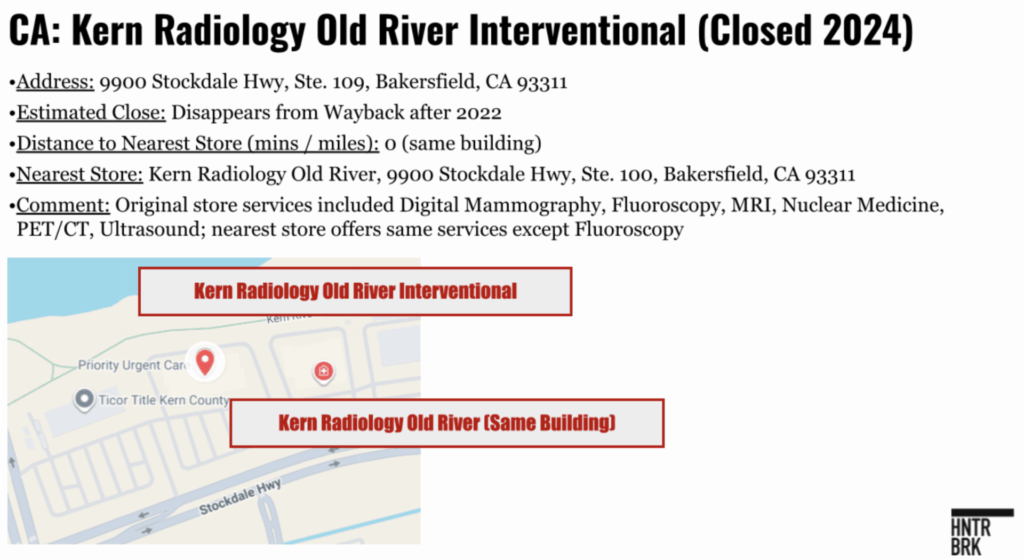

Then there’s Kern Radiology. Historically, RadNet listed two centers at its Old River site in Bakersfield, California — with the same address, but different suite numbers. One closed, and the one that remains offers all but one of the same services, according to their websites.

So were those locations truly closed, or would it be more accurate to say they were merged?

There are dozens of similar examples — a pattern that, in aggregate, appears to more than double RadNet’s same-center growth.

Turning to the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, independent financial analysts who shared research with Hunterbrook pulled historical snapshots of RadNet’s “Find an Imaging Center” tool on its website. This allowed them to see which sites disappeared from year to year. Once they verified that centers had closed, Hunterbrook checked how far each was to another RadNet center. If it was a less than 15 minute drive, we called it a “notable closure.” There were 44 of them between 2022 and 2025.

RadNet may have a valid business case for closing a center and consolidating, but the move plays havoc with same-center sales math. Imagine two centers, A and B, five minutes apart. Each does $3 million in revenue. Together, they make $6 million in a year. If demand is flat, the next year they’ll still make $6 million. The same-center growth is zero.

Now, say that RadNet closes center B and routes its patients to A. B is gone from the same-center calculation — but its revenue has simply shifted to A, the RadNet location a few minutes away.

So A can show 100% same-center sales growth, thereby helping to drive up the company’s average. But nothing fundamental happened. This isn’t DeepHealth helping RadNet get more business. The volume didn’t grow, it merely changed addresses.

A financial analysis shared with Hunterbrook shows that this has had an enormous impact on RadNet’s same-center sales — under a range of assumptions, conservative and aggressive. For details, see this exhaustive footnote.1

According to the analyst’s model, the company’s decision to close centers near existing RadNet locations potentially accounts for up to 57% of RadNet’s reported same-center growth between 2022 and 2025. The company’s reported same-center sales growth averaged about 6% a year over that period. But minus the artificial boost that comes from consolidating centers, the real growth looks more like 2.5% to 3%, the analysis found.

In other words, RadNet remains a mature chain of clinics facing unrelenting reimbursement pressure. Which is just how CFO Stolper described it back in 2019, before the rebranding began. “We could assume in a normalized environment … kind of a 1% to 3% same-center growth,” he told investors.

RadNet may now be setting the stage for more consolidations.

Of the 400 centers on its website, at least 100 fall within about a quarter mile of another RadNet location, Hunterbrook found. There were 28 addresses that were used for multiple RadNet locations, and seven of those addresses were identical down to the same suite number.

That includes an address in central Phoenix. The RadNet website and the sign out front show “Breastlink” and “Arizona Diagnostic Radiology,” as though they’re separate. But there’s seemingly only one clinic licensed at that address, Arizona state records show. “BreastLink” is registered as a trade name with the state, but only “Arizona Diagnostic Radiology Group” is registered as a corporation. American College of Radiology’s accreditation contains multiple entries at that address, including “Arizona Diagnostic Radiology Group DBA Breastlink” and “Arizona Diagnostic Radiology, LLC.”2

A manager at the location wasn’t immediately available for comment and didn’t respond to a message. An employee at a reception desk said Breastlink and Arizona Diagnostic Radiology are one business.

And it does look like one big center, but RadNet’s website counts it as two — at least for now. RadNet could ultimately consolidate the two centers, and their sales.

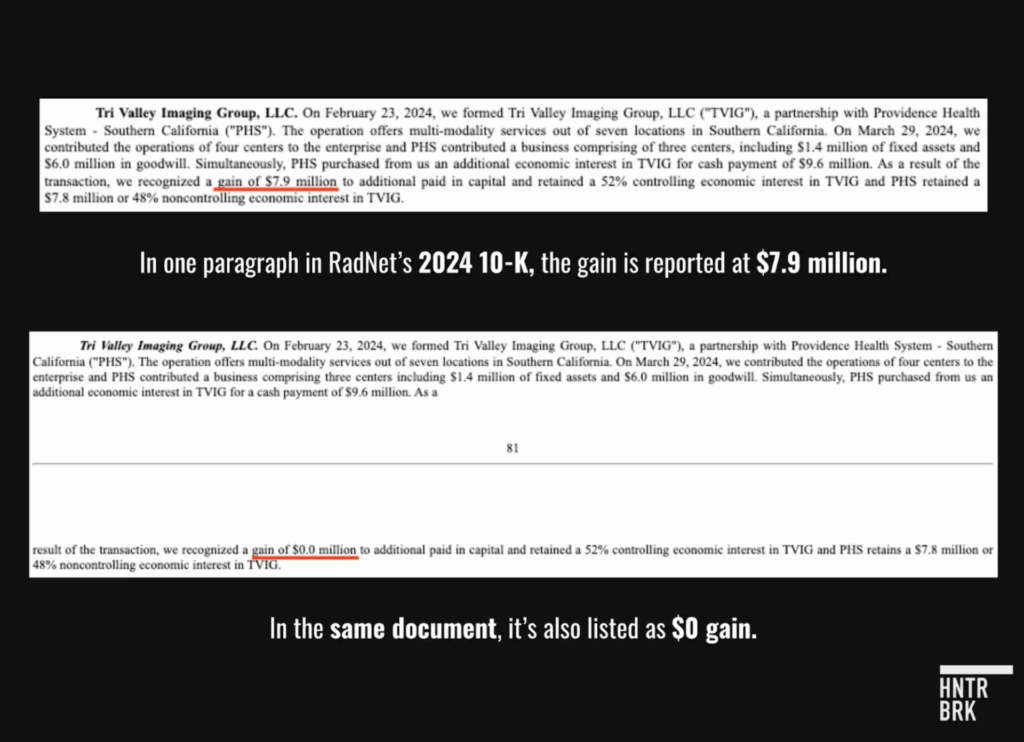

Chaos in the Financials

The kindest thing you can say about the company’s bookkeeping is that it’s chaotic.

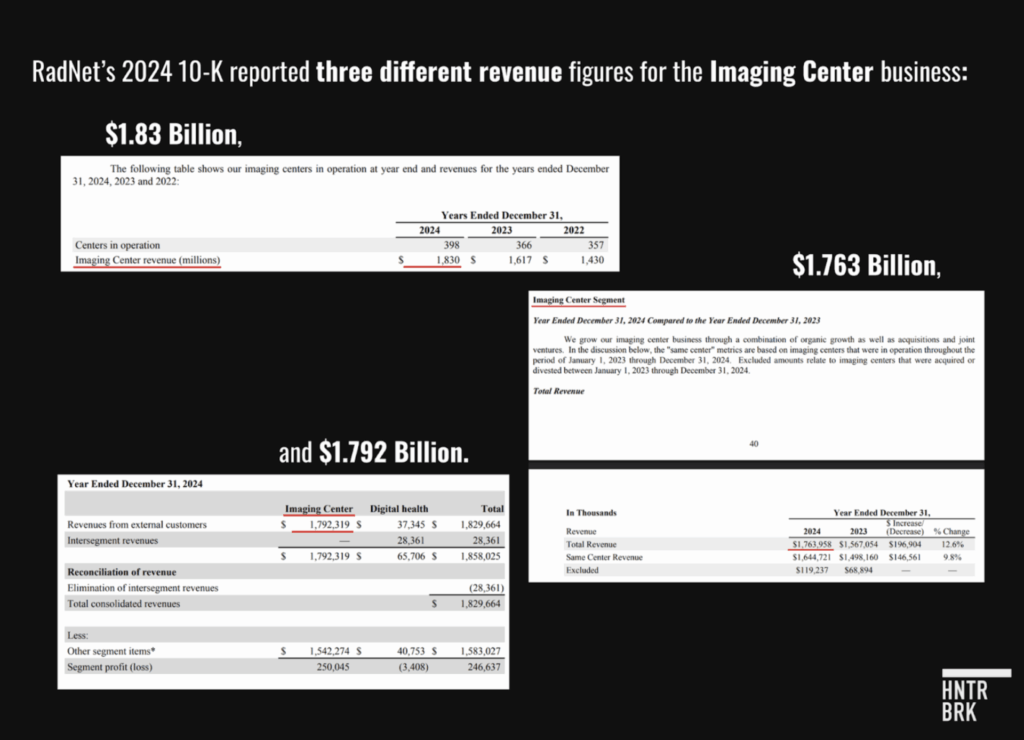

In its 2024 10-K, RadNet reported three different revenue figures — $1.83 billion, $1.763 billion, and $1.792 billion — for its old Imaging Center business, the core business that dwarfs Digital Health.

There appear to be additional, smaller errors throughout the company’s financial statements.

In 2024, RadNet sold a portion of its stake in a small business called Tri Valley Imaging. In one spot, the gain is reported at $7.9 million. In another spot, it’s zero.

Other apparent accounting practices may be more concerning.

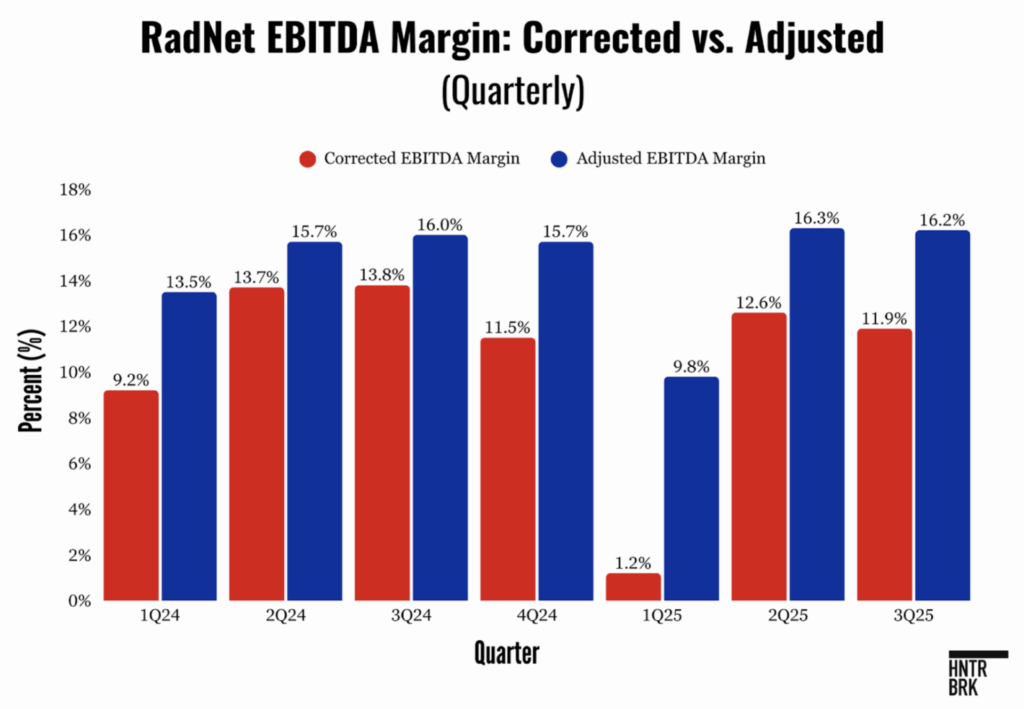

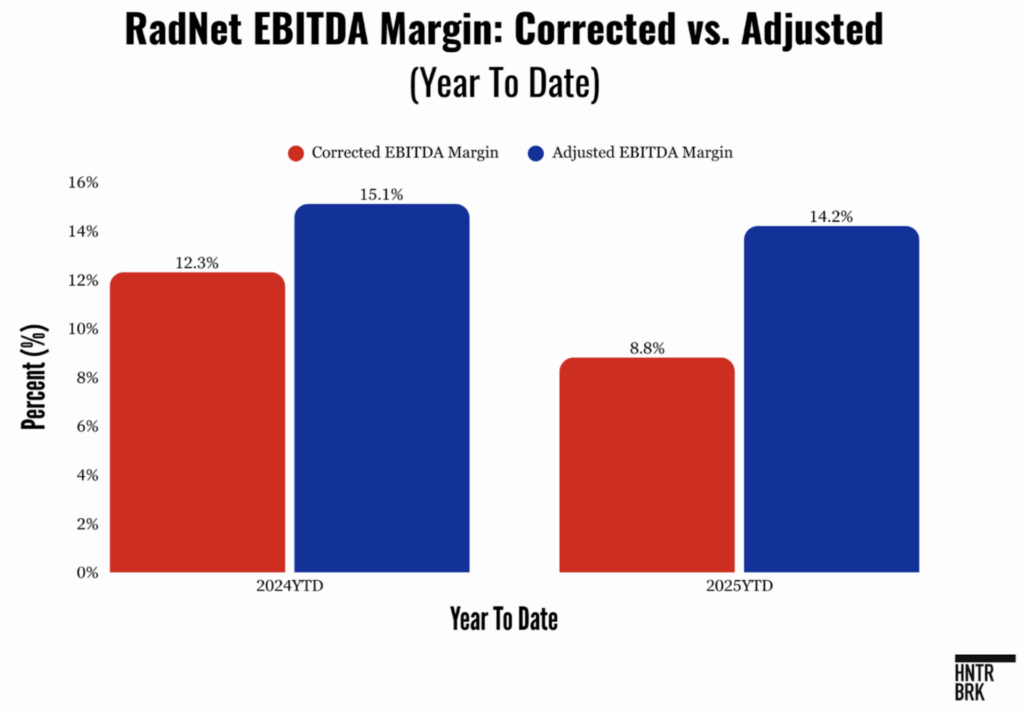

In particular, RadNet appears to exclude stock-based compensation and certain research and development costs from its calculation of adjusted EBITDA, the latter of which is a departure from standard accounting practice. This enabled RadNet to present a much more optimistic view of its operating margins.

For a company with heavy ongoing capital expenditures that are required to keep its technology up to date, treating some R&D expenses as a distinct, ignorable add-back rather than a core operating expense is a bold choice. If you treat those costs as real, the margin expansion seen in certain periods vanishes.

In fact, once stock compensation is accounted for, margins are actually shrinking. (For the purposes of this piece, we will call EBITDA that includes stock-based compensation and R&D “Corrected EBITDA” and RadNet’s calculation “Adjusted EBITDA.”)

For a sense of why this matters: RadNet’s stock soared 40% in the weeks after reporting its second quarter earnings — in which its adjusted results showed margin improvement year-over-year. On the call, an analyst called this number “awesome.”

But after accounting for stock based compensation and the capitalized R&D expenses, Corrected EBITDA margins actually dropped.

RadNet’s recent valuation tells the real story. Before RadNet embarked on its AI transformation, its stock sold for around 8 to 10 times its adjusted EBITDA. That’s similar to the valuation of RadNet’s peer Lumexa Imaging, which IPO’d last week as LMRI, and is now trading at 10 to 12 times EBITDA.

RadNet now trades at around 19 times. (And remember: The Adjusted EBITDA number itself has become more aggressive; it’s trading at more like 30 times what we have called its Corrected EBITDA.)

If you applied RadNet’s old multiple to the imaging center business, and subtract it from RadNet’s total market capitalization, then the implied value of the Digital Health business is more than $3 billion — almost 40 times its revenue.

Notably, RadNet’s core business has been growing, so the multiple for its imaging centers may have risen from around 8–10 times to 12–15 times on its own. RadNet has increased the volume of higher-margin imaging like PET scans, among a range of other tailwinds like an aging population seeking more imaging.

But even with an optimistic valuation for the core Imaging Center business, Digital Health is being valued as a billion-dollar business — a staggering price tag for a unit whose products are having trouble getting traction among external customers.

Whatever the reality, the perception that the company has been on a technology tear has been lucrative for those in the know. In the last 24 months, insiders have sold more than 780,000 shares — worth $50.9 million. CFO Mark Stolper sold 35,000 shares in September, or roughly a third of what he owned, excluding his options. There have been no open-market purchases by insiders since 2021.

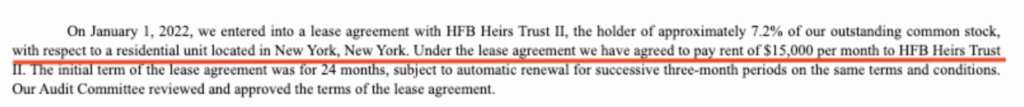

The CEO, Berger, is not among the sellers. But the company’s financial statements also disclose that RadNet is paying $180,000 a year so that a trust set up for Berger’s children can rent an apartment in New York — even though the company is headquartered in California.

In other words, someone is winning at the AI casino. In the long-run, it just may not be investors.

Authors

Bethany McLean is an advisor and contributor to Hunterbrook. McLean worked for thirteen years at Fortune. She and fellow reporter Peter Elkind co-authored The Smartest Guys in the Room: The Amazing Rise and Scandalous Fall of Enron. She then became a Contributing Editor at Vanity Fair, where she continued to cover business scandals.

Andrew Ford is an investigative journalist who exposed systemic flaws and prompted reforms in healthcare, business, policing, and state government. His reporting was published by ProPublica, USA Today, The Arizona Republic, Asbury Park Press, and Florida Today. He holds a journalism bachelor’s from the University of Florida and is based in Phoenix, AZ.

Laura Wadsten is an investigative journalist specializing in healthcare. She began her career reporting on antitrust and healthcare as a Correspondent for The Capitol Forum, a premium financial publication. Laura was a Hodson Scholar and Editor-in-Chief of The News-Letter at Johns Hopkins University, where she earned a B.A. in Medicine, Science & the Humanities.

Editor

Jim Impoco is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek who returned the publication to print in 2014. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has a Master’s in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2025 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided “as is” without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.

After Hunterbrook identified inconsistencies in RadNet’s reported location counts and the disappearance of certain centers from its public center locator, we worked with financial analysts to examine the issue. What follows summarizes their methodology and assumptions.

The analysts began by reconstructing RadNet’s “same-center” base using only information the company reports in its SEC filings. RadNet’s 10-Ks and 10-Qs define “same-center” revenue as covering only those imaging centers that were in operation for the entire measurement period (for example, from January 1 of the prior year through the end of the reporting period) and explicitly excluding acquired, divested, or minority-owned, nonconsolidated joint ventures. Because RadNet does not disclose a standalone same-center count, the analysts inferred it by starting with the company’s headline beginning-of-period center figure, subtracting minority-owned joint ventures, and then subtracting centers RadNet identifies as divested during the period. Where RadNet had divested nonconsolidated joint ventures, the analysts adjusted to avoid double-counting those locations as closures, since they were never eligible for inclusion in same-center metrics to begin with.

In parallel, the analysts attempted to identify which sites had actually been shuttered. To do this, they scraped the current version of RadNet’s center locator and compared it with archived versions of the same page obtained through the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. For each snapshot, they catalogued the site name, address, phone number, and listed services. When a location disappeared from the locator, the analysts spot-checked addresses and phone numbers to ensure the change reflected a genuine closure rather than a renaming. They then mapped each closed site and calculated driving time to the nearest RadNet center. If the shuttered facility was within a 15-minute drive — often far closer, with several in the same building as surviving centers — the analysts classified it as a nearby closure likely to result in patient volume shifting to another RadNet location.

Because the Wayback Machine collects snapshots irregularly, the analysts noted that the precise closure date of any given center cannot always be pinned to the specific quarter in which the location vanished from the archive. For example, a site closed in late 2024 might not disappear from archived pages until mid-2025. While this introduces some year-to-year timing noise, it does not materially affect the cumulative analysis across the 2022–2025 period.

To estimate how much these consolidations inflated RadNet’s reported same-center revenue growth, the analysts used a deliberately straightforward model. For each year, they estimated the number of nearby closures, multiplied that by an average revenue per center, and treated the resulting figure as volume likely to have migrated to the surviving sites. Because RadNet does not report revenue at the site level, the analysts assumed the closed centers generated the same average revenue as the centers remaining in the same-center pool. (This may be a conservative assumption: If the closures are designed to improve same-center sales, then the closed centers might, on average, be the ones with higher volume. It could also be an aggressive assumption, if RadNet is operating like a normal business and simply keeping open its more successful centers.)

The analysts also assumed RadNet retained all patient volume from closed facilities — an assumption that may overstates the effect, since some patients inevitably seek care elsewhere, but which keeps the calculation simple and transparent.

Subtracting this estimated consolidation “uplift” from RadNet’s reported same-center growth yielded the analysts’ estimate of underlying organic growth. Their conclusion: Using these assumptions, roughly half of RadNet’s reported same-center revenue growth from 2022 through 2025 can be explained by the mechanical effect of closing centers located near other RadNet centers. Adjusting for this effect implies underlying growth of roughly 2.5%–3%, broadly consistent with the 1%–3% range RadNet itself described as “normalized” before its AI rebranding campaign began.

If one were to assume 50% retention by the new centers, the store closures would still be responsible for 28% of the company’s same-center growth; and at 75% retention, they would be responsible for 42%.

While Arizona Diagnostic Radiology Group, LLC is registered as a foreign LLC with the state of Arizona, a search for “Breastlink” on the Arizona Corporation Commission site yielded only trade names, which are similar to “doing business as” names, according to the Arizona Secretary of State. The Arizona Secretary of State site showed Arizona Diagnostic Radiology Group, LLC was the applicant for the BreastLink - Park Central trade name