Ubiquiti: The U.S. Tech Enabling Russia’s Drone War

Ubiquiti is led by Memphis Grizzlies owner Robert Pera. He pledged to tighten controls on his products years ago — so why are Russian military units sending Ubiquiti vendors thank-you notes?

By: Jenny Ahn, Blake Spendley, Andrew Ford, Till Daldrup, Michelle Cera

Editor: Jim Impoco, Sam Koppelman, Wendy Nardi

Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is short $UI and long a basket of comparable securities at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. See full disclosures on our website. Our affiliate Hunterbrook Law is in conversations with litigation firms regarding potential private litigation on behalf of Ukrainians impacted.

Ubiquiti radio bridge antennae serve a critical communications need for the Russian military in Ukraine, including for drone operations, according to our investigation. A Ukrainian communications officer estimated 80% of Russian radio bridges they’d observed on the battlefield were made by Ubiquiti. “Ubiquiti is made for regular people — basically plug-and-play. Tons of tutorials on YouTube,” the officer explained. “There is no alternative,” a Russian vendor told Hunterbrook. The U.N. has called Russia’s drone attacks against civilians crimes against humanity.

Hunterbrook identified at least nine Russian military units accused of war crimes, or individuals associated with those units, that use Ubiquiti equipment in Ukraine, based on a review of Telegram posts and open-source materials. One fundraising group that said it had donated Ubiquiti antennae to Russian forces is run by a terrorist convicted of the 2015 bombing of a Ukrainian government building.

Hunterbrook tested how easily export-banned Ubiquiti equipment could reach Russian forces. Posing as a Russian military procurement officer, a reporter contacted Russian vendors and multiple official Ubiquiti distributors worldwide. Nearly a dozen agreed to sell export-banned equipment. One vendor even shared thank-you letters they said were for providing Ubiquiti equipment to the Russian military. Official distributors, including U.S.-based Multilink Solutions, agreed to ship to third countries like Turkey for pickup even after the customer identified as being based in Russia — a known sanctions evasion tactic flagged by U.S. authorities.

The total value of Ubiquiti shipments crossing the border into Russia surged 66% after the invasion despite U.S. and EU sanctions and export controls, according to Hunterbrook’s analysis of trade records. Shipments include the latest Ubiquiti models released after the ban, suggesting ongoing access to the company’s supply chain.

Official Ubiquiti distributors appear to have continued supplying Russia after the invasion, sometimes rerouting shipments through intermediaries in high-diversion-risk countries like Turkey and Kazakhstan, trade records show. Some appear to have used intermediaries later sanctioned by the U.S. for export control evasions.

Russian vendors use Ubiquiti’s trademarked name and logos despite Russian intellectual property laws that would allow quick takedowns and potential criminal prosecution for infringers. In 2025, Ubiquiti filed to protect its stylized “U” logo in Russia with the Russian federal intellectual property agency — and won — but took no apparent action against these Russian vendors.

Ubiquiti’s global distribution network is riddled with compliance red flags beyond Russia. In Paraguay, the founder and president of Flytec Computers — once responsible for 13% of Ubiquiti’s revenues — has been accused of smuggling, massive tax evasion, and money laundering in Brazil, and of involvement with the illegal housing of a large-scale bitcoin mining operation. In Mexico, Ubiquiti distributor SYSCOM was quietly acquired in 2021 by Hikvision, a Chinese state-owned company the U.S. designated that same year as part of China’s military-industrial complex.

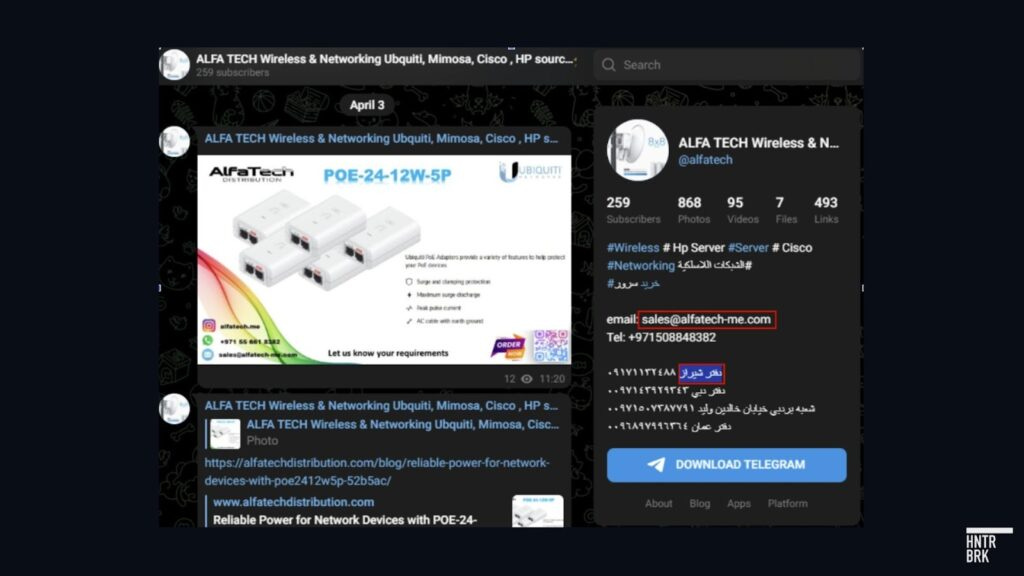

More than a decade after Ubiquiti was fined for “reckless disregard” for sanctions obligations when its products ended up in Iran, Hunterbrook found Ubiquiti products may be still flowing there. A current official distributor listed on Ubiquiti’s website, Yemen-based Alfa Tech, may be operating branches in Shiraz and Tehran, according to its own Persian-language advertisements. In 2014, U.S. regulators fined Ubiquiti after at least $589,000 worth of prohibited equipment was diverted to sanctioned Iranian entities. CEO Robert Pera told Forbes at the time, “It can’t happen again. If it does, I’ll be in a lot of trouble.”

Ubiquiti openly admits “we do not have any visibility” over purchases from its distributors, but legal experts told Hunterbrook that’s not a viable defense. U.S. export controls and sanctions operate on a strict liability basis — meaning, even unwitting violations are still violations. “Ignorance is not really a practical excuse, or rather, a legal excuse,” a former senior State Department sanctions official told Hunterbrook. A sanctions compliance lawyer added, “You, doing very little effort, were able to determine that it’s available for purchase by the Russian armed forces. … The company’s compliance team should be taking additional steps to prevent that.”

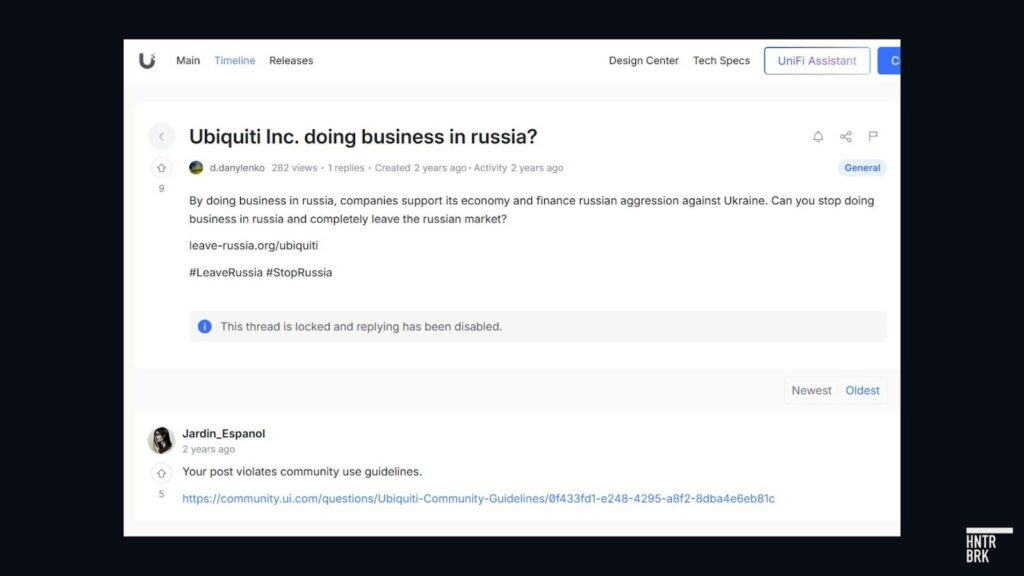

Industry experts told Hunterbrook that Ubiquiti likely has the technical means to trace products appearing inside Russia — and may already be doing so. As of September 2025, Ubiquiti appeared to have placed an IP-based ban on firmware updates for Russian users, based on complaints on a Russian forum, suggesting the company can identify device locations. Experts said Ubiquiti could even trace specific hardware back to the original distributor through serial numbers and MAC addresses. Ubiquiti shut down a user forum discussion raising concerns about its Russia business with the message, “Your post violates community guidelines.”

Ubiquiti did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Read the full version of our investigation on our website, where you will find eye-opening photos and graphics, as well as footnotes outlining our methodology.

A Russian soldier climbs a tower, carrying an antenna, a recent Russian newsclip shows. On the antenna is the logo of Ubiquiti ($UI), a $34 billion American tech company.

In the segment, a Russian signalman describes the importance of their job: “A break in communications means total loss of control over combat operations.”

The reporter agrees, “No communication, no front.”

Around the world, Ubiquiti’s products are so popular, they made its CEO the youngest owner of an NBA team, the Memphis Grizzlies, in 2012.

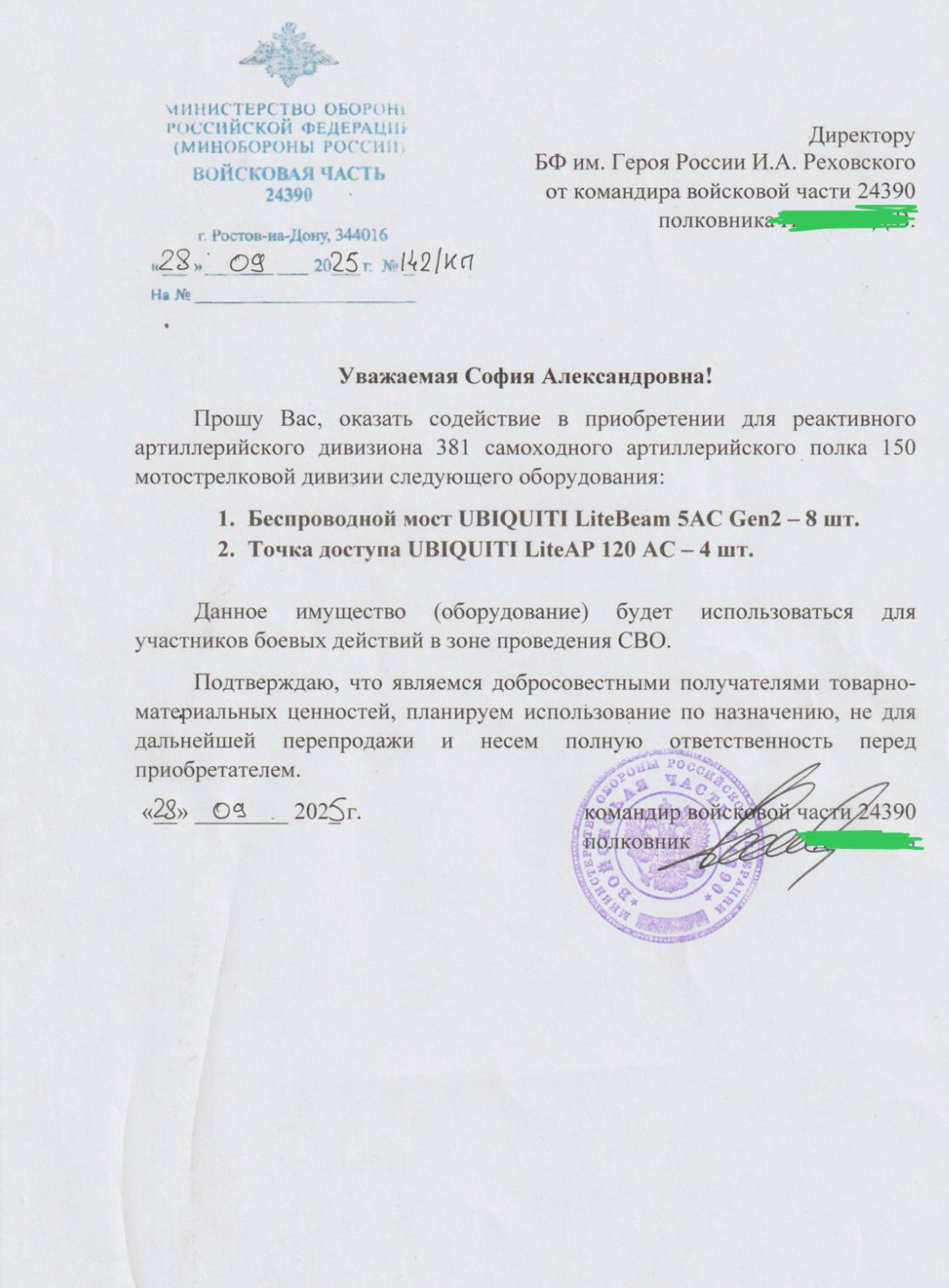

And Hunterbrook has thank-you letters supplied by a Russian Ubiquiti vendor in which members of the Russian military express their gratitude for the technology.

A monthslong Hunterbrook Media investigation found that Ubiquiti radio bridge antennae — devices used to extend Wi-Fi signals across long distances — serve a critical communications need of the Russian military, including in drone operations. The U.N. has called Russia’s drone attacks against civilians crimes against humanity. There is no adequate alternative to Ubiquiti, multiple sources, including soldiers on active duty in the war zone, told Hunterbrook.

Despite U.S. sanctions and export controls designed to keep them out of Russian hands, Ubiquiti products appear readily available. A Hunterbrook reporter, posing as a Russian army procurement officer, found nearly a dozen Russian stores standing ready to supply Russian combat troops with Ubiquiti equipment. Hunterbrook also found numerous social media posts by Russian fundraising groups and military officials seeking or reporting on Ubiquiti donations to various military units fighting in Ukraine, including some units accused of war crimes.

Enabling the supply chain is Ubiquiti’s dense network of distributors, despite layers of sanctions and export controls designed to prevent those flows.

Ubiquiti did not respond to Hunterbrook’s repeated requests for comment — but the company has said in the past that it doesn’t know where its products end up. Experts told Hunterbrook that’s no excuse.

There Is No Alternative

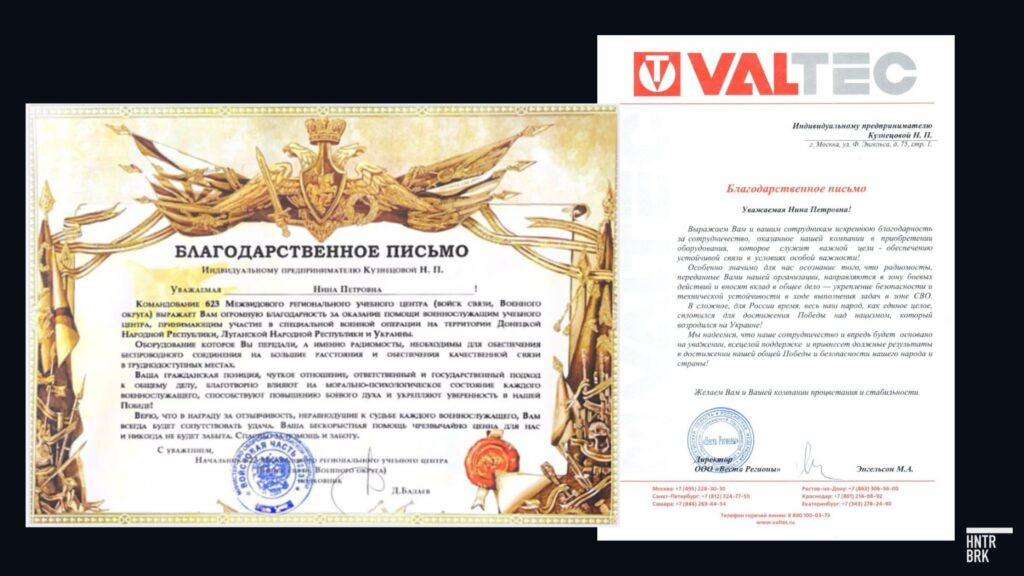

The newsclip was shared with a Hunterbrook reporter — posing as a Russian officer seeking to purchase Ubiquiti equipment for the Russian military — by Nina Kuznetsova. Kuznetsova has multiple Russian storefronts with domain names like ubiquiti.ru that openly sell Ubiquiti products banned from export to Russia since the war.

A representative at Kuznetsova’s store also shared thank-you letters they said were for providing Ubiquiti equipment to the Russian military.

“Radio bridges are necessary to provide wireless connection over long distances and to provide high-quality communication in hard-to-reach areas,” one letter said.

Another thanked Kuznetsova for the radio bridges “sent to the combat zone.”

Ubiquiti was founded in 2005 with a focus on “democratizing network technology on a global scale.” Its revolutionary idea — offering affordable, easy-to-use, high-quality networking equipment with local control and privacy — helped Ubiquiti spread internet connectivity to remote areas around the globe.

But that same model appears also to have made Ubiquiti the equipment of choice for the Russian military’s frontline communication needs, Hunterbrook Media found.

“There are no stable, inexpensive alternatives to this manufacturer,” said a message forwarded from Kuznetsova by her staff. “95 percent of the shipments for the SVO are Ubiquiti gear,” one of her representatives chimed in. “SVO” is an acronym for “special military operation,” the Russian euphemism for the war against Ukraine.

Ukrainian sources echoed those claims.

“They simply have no alternative,” a Ukrainian communications officer who uses the call-name Django told Hunterbrook in an interview from the war zone.

Django estimated about 80% of Russian radio bridges observed on the front line are Ubiquiti, adding he has yet to spot rival products like Mikrotik’s.1 Radio bridges are antenna-based devices that wirelessly connect two distant locations so they can share the same internet or data network.

“Ubiquiti is made for regular people — basically plug-and-play. Tons of tutorials on YouTube,” he explained. Competitor brands, like Starlink, can be disabled remotely or, like Mikrotik, are difficult to use, another Ukrainian signalman told Hunterbrook.

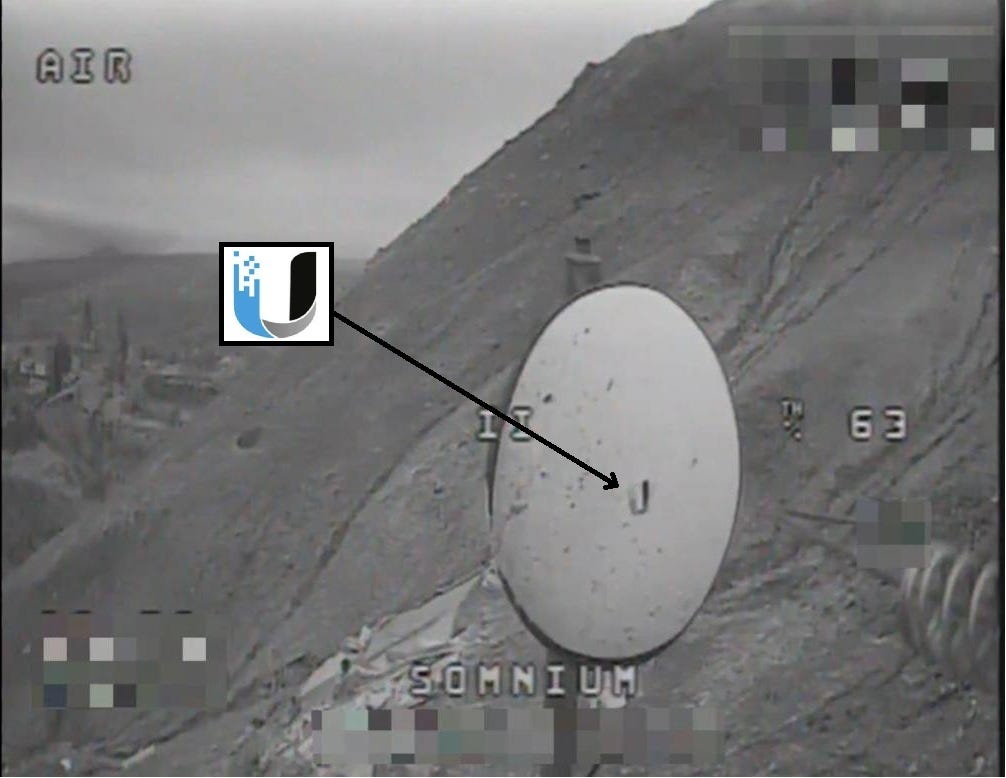

Hunterbrook discovered numerous Telegram posts showing aerial footage of Russian bridge antennae identified by Ukrainian experts as Ubiquiti’s on the battlefield. In one Ukrainian drone video obtained by Hunterbrook, a church steeple is seen housing over a dozen antennae with features consistent with Ubiquiti radio bridges.2

A post by Serhii “Flash” on June 19, 2024, on his Telegram channel showing what appears to be drone footage of an antenna, next to a photo of a Ubiquiti PowerBeam. “We are recording the appearance of such antennas in all directions,” the post says (translation by Hunterbrook). Source: Telegram

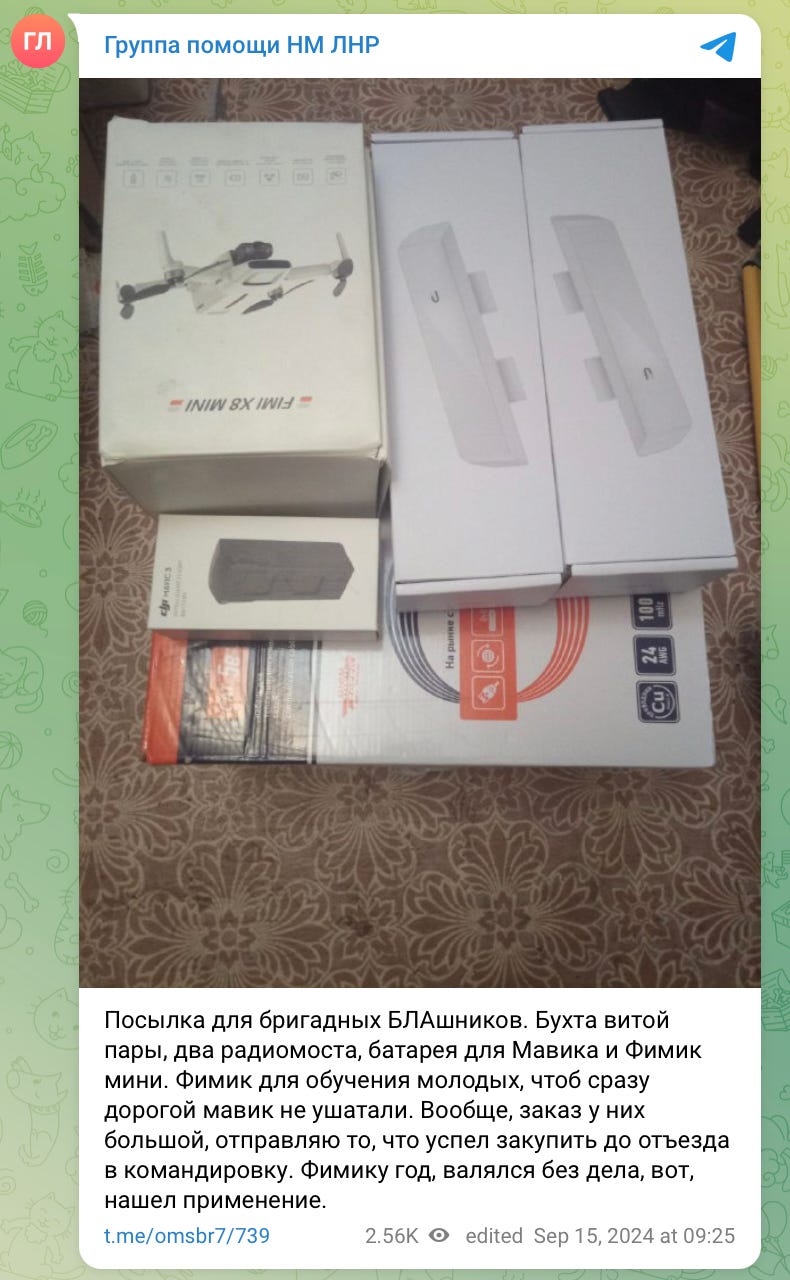

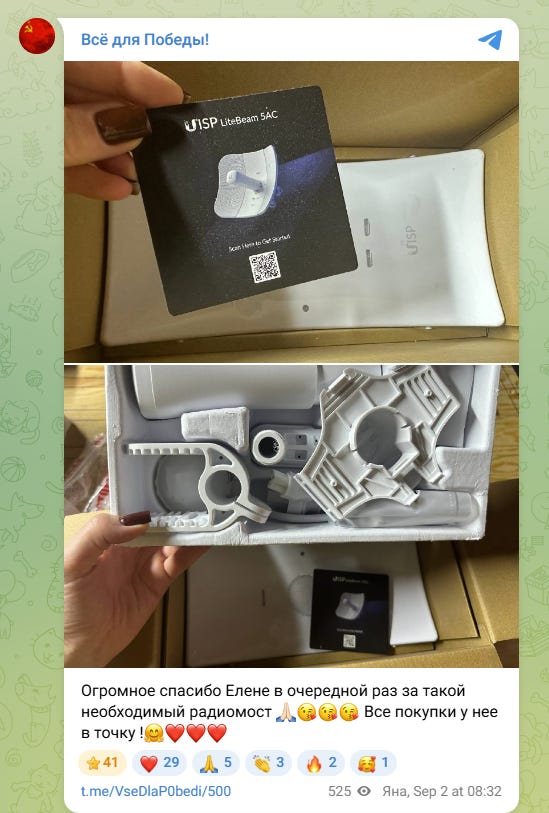

The Russian war effort is heavily crowdfunded, according to multiple reports, and troops frequently post on social media requesting or expressing thanks for donated gear like Ubiquiti’s intended for Russian troops on the war front — including specifically for drone operations.

“We thank the people’s militia assistance group for providing communications equipment in the form of Ubiquiti antennae,” a soldier said in a video posted on Telegram. “Reliable communications are the key to success. The enemy will be defeated — victory will be ours.”

A September 15, 2024 Telegram post by the LPR People’s Militia Assistance Group showing a photo of a drone and communication devices, including Ubiquiti bridge radios, that the group called “a parcel for the team’s UAV operators.” Source: Telegram

Nine of the military units that received Ubiquiti gear, or individuals associated with those units, have been accused in various news outlets of having committed war crimes, Hunterbrook found.

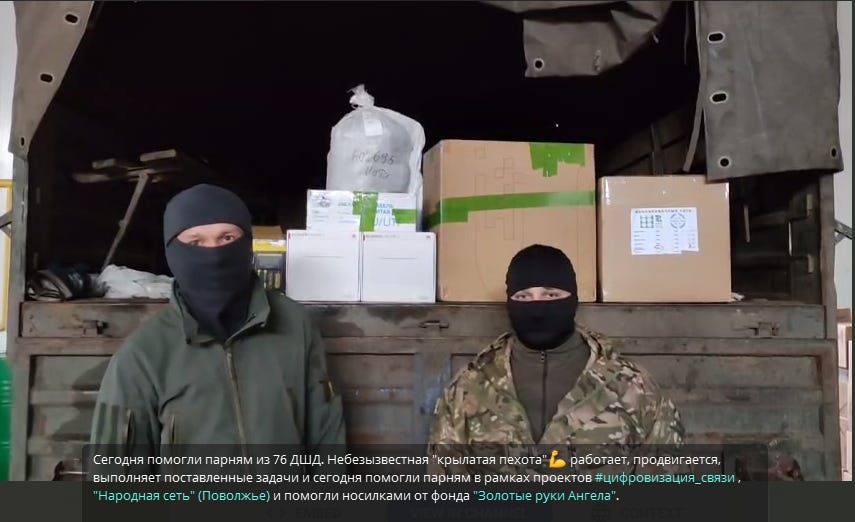

In a recent Telegram post, “Ghost_of_Novorossia” — a fundraising group run by a terrorist convicted for organizing the 2015 bombing of a Ukrainian government building — claimed to have donated Ubiquiti antennae to the 76th Guards Air Assault Division. This division was accused of looting villages in Kherson Oblast and massacring civilians in Bucha in 2022.

Among the Russian communication needs they serve, Ubiquiti’s radio bridges provide communication links to pilot drones, transmit live video, and find targets, Django said. Hunterbrook also found Russian social media posts, such as this one, indicating Ubiquiti antennae serve as a communications backbone for drones.

The cost of this connectivity can be measured in blood.

Russian drones, including “kamikaze” drones that carry explosives and are designed to crash into a target, now account for 60%-70% of casualties on the battlefield, The New York Times reported. In some areas, the drones intentionally hunt and kill Ukrainian citizens to spread terror, according to Human Rights Watch. The U.N. Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine recently called these acts crimes against humanity and war crimes.

When asked, Django agreed that there would be fewer casualties if it weren’t for Ubiquiti antennae.

“If their supply is disrupted, I believe that coordination between intelligence and FPV operators will be disrupted, and thus there will be fewer sorties and fewer casualties, both among the military and the civilian population,” he said. FPV, or first-person view, refers to drones that allow pilots to see through the drone’s camera in real time.

In Kherson, a Ukrainian city bordering occupied Crimea, drone attacks on residents have been so frequent, they’ve earned the gruesome moniker “human safari,” according to the Ukrainian monitoring group Tochnyi. “5364 civilians hit” by Russian drones since December 2023, the group said.3

And one of the largest Russian units that has been deployed to Kherson — Russia’s 18th Combined Arms Army — had, as of October 2025, received Ubiquiti bridge antennae from a Russian fundraising group, Hunterbrook found. The Telegram group going by the name “Brotherly Aid” posted in October that it had sent two Ubiquiti antennae to the “Kherson communications team” — a reference to the 18th CAA. In a separate post, the group claimed it had “repeatedly assisted” the 18th CAA in the past.

“They just mercilessly shell this poor city and poor people,” Oleksandra Ishchenko, a former resident of Kherson, told Hunterbrook. Ishchenko said she hasn’t been back to her hometown in years but hears of the drone attacks from family and friends who remain there.

“No one is protected from this.”

Ubiquiti’s Tolerance of Its Impersonators

In October 2025, Hunterbrook went undercover to test how hard it would be to obtain Ubiquiti equipment on the Russian market. Posing as a Russian military officer procuring goods for the Russian troops fighting in Ukraine, a Hunterbrook reporter contacted over a dozen Russian e-commerce sites like Kuznetsova’s openly selling Ubiquiti items in Russia.

Many of the Russian Ubiquiti vendors — including ubiquiti.ru, ubnt.ru, ubiquiti-russia.com, ru-ubiquiti.ru — have “Ubiquiti” in their domain name. Their sites look like official Ubiquiti outlets, and some brandish the Ubiquiti name, logos, product images, and styling. Ubiquiti technical resources are sometimes virtually identical (see here and here). Some of these vendors even claim to be Ubiquiti’s “official” distributor in Russia.

Certain vendors, Hunterbrook found, are suppliers to sanctioned entities. According to Russian government procurement records, UbiRussia.ru, for example, is a supplier to the Moscow Power Engineering Institute, subject to U.S. sanctions for its reported ties to the Russian military’s missile program.

At least one vendor is itself sanctioned. According to a privacy disclosure on its website, ubiquiti-Russia.com belongs to a company named Elecom, which was sanctioned by the U.S. in 2024 for conveying restricted electronics into Russia.

Hunterbrook gave each shop the same proposition: Our military unit needs Ubiquiti equipment for operations in occupied Ukrainian territories.

The reporter asked for popular Ubiquiti wireless bridges — items like Ubiquiti’s airMax PowerBeam and airMax NanoStation.

The items are classified by U.S. export authorities as sensitive dual-use goods requiring a license for export to most countries under normal circumstances.4 Immediately following Russia’s invasion, however, the U.S. effectively placed a blanket ban on their export to Russia, labeling them as high-priority tech items that Russia needs for its “brutal attack on Ukraine.5” Moreover, U.S. sanctions laws prohibit U.S. companies from sales of any kind to Russian-occupied territories in Crimea, Donetsk, and Luhansk.

Nearly a dozen Russian dealers confirmed our shopping list and promised to deliver the items to military units in the occupied territories.

One vendor, Comptek, had a condition, however: a minimum order of at least $100,000.

Why?

“You want sanctioned equipment. We carry orders starting at $100,000,” a company representative said.

When asked, two of the vendors told Hunterbrook that they no longer have an official relationship with Ubiquiti, and that they receive their products through “parallel import” — a term to describe sourcing goods outside authorized distribution channels, often to bypass Western export controls.

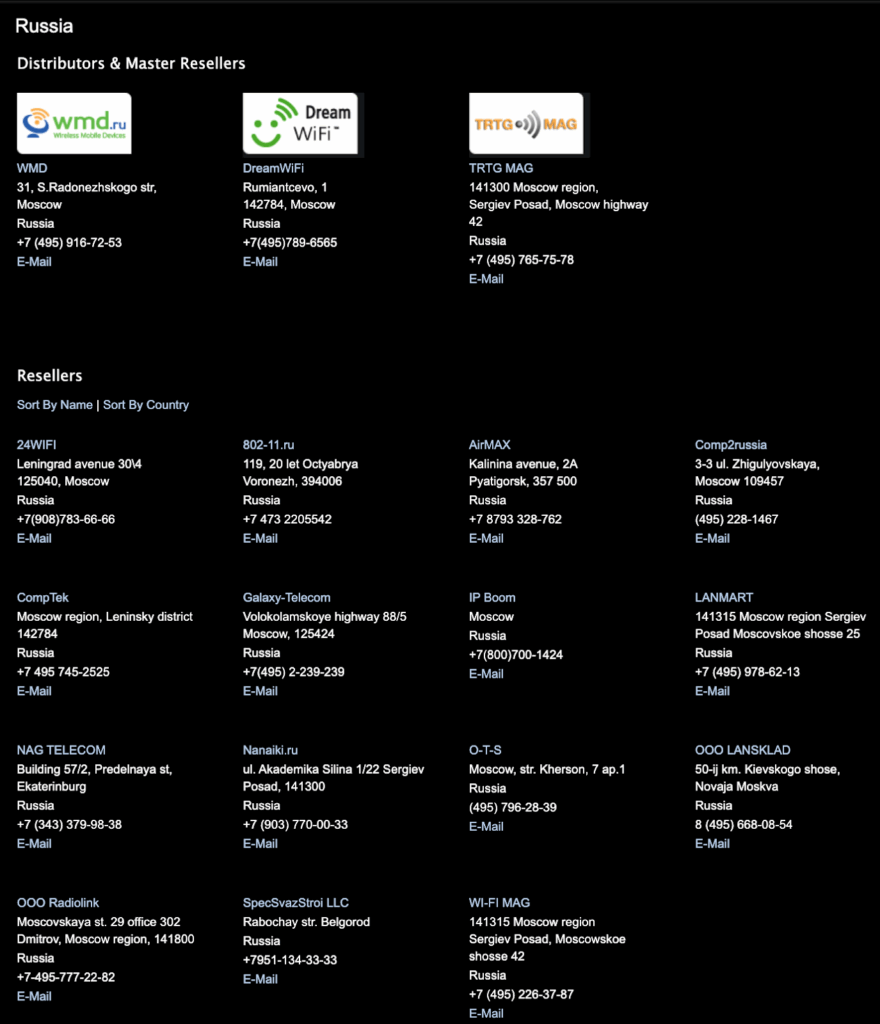

But the exact nature of their ongoing relationship is murkier. Unlike its competitors Cisco, Fortinet, Siemens, and HPE/Aruba, Ubiquiti did not announce it would leave Russia after the 2022 invasion. Ubiquiti’s website no longer contains a list of its official distributors and resellers in Russia and Belarus, but an archived snapshot of the site taken in 2014 shows a long list of historic Russian distributors, many of which still operate and sell Ubiquiti products in Russia.6

And aside from tweaking its website, Ubiquiti appears to have done little to distance itself from its former Russian partners that continue to claim ties to the company.

Ubiquiti’s intellectual property policy explicitly bans its distributors from using its trademarked names and logo without written authorization. Russia’s IP protection laws should allow Ubiquiti to take down sites bearing its domain name, with infringers facing potential civil, administrative, and criminal prosecution. In fact, in 2025, Ubiquiti moved to further secure its stylized “U” logo in Russia, filing a patent application with Russian federal intellectual property agency Rospatent, and won.

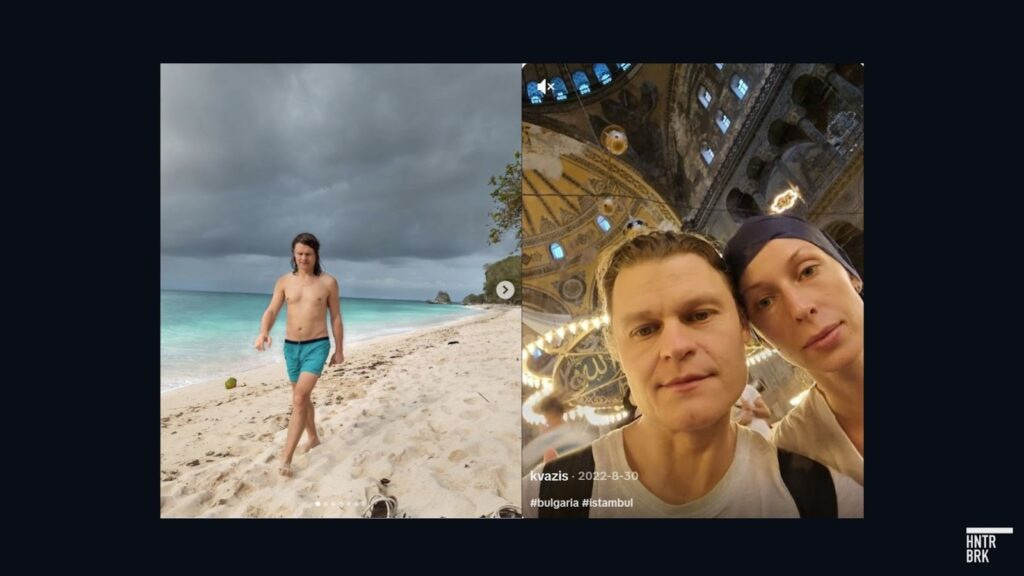

And yet, the Russian websites containing imitation Ubiquiti logos were up and running as of publication. That includes ubiquiti.ru — whose proprietor is not exactly trying to hide what she is doing. Kuznetsova resides in an apartment on the iconic Leninsky Avenue in Moscow, according to a Hunterbrook review of Russian business records. Her business partner — and based on their names, presumably her son — Andrey Kuznetsov has spent the last few years frequently traveling across Europe and Asia, even posting about about it on social media.

Charting Ubiquiti Supply Routes to Russia

Amid the layers of sanctions and export controls, how is Russia getting its hands on Ubiquiti gear?

To find out, Hunterbrook also reached out to dozens of official Ubiquiti distributors — third-party global partners contracted to market and distribute Ubiquiti goods on its behalf. Ubiquiti relies heavily on nearly 600 third-party distributors and resellers worldwide rather than internal sales teams for marketing and distribution.7

Posing as a Russian customer, a Hunterbrook reporter asked them for Ubiquiti bridge antennae.

One company, ITsupport, based in Armenia, agreed to ship the U.S.-export-controlled items directly to Moscow. Two companies refused to sell at all, consistent with U.S. export policies on Russia.

Most of the others that responded refused to ship the goods directly to Russia, but agreed to deliver them to an address in their own country or to a third country for pickup — sometimes after having heard the end user was the Russian military fighting against Ukraine.

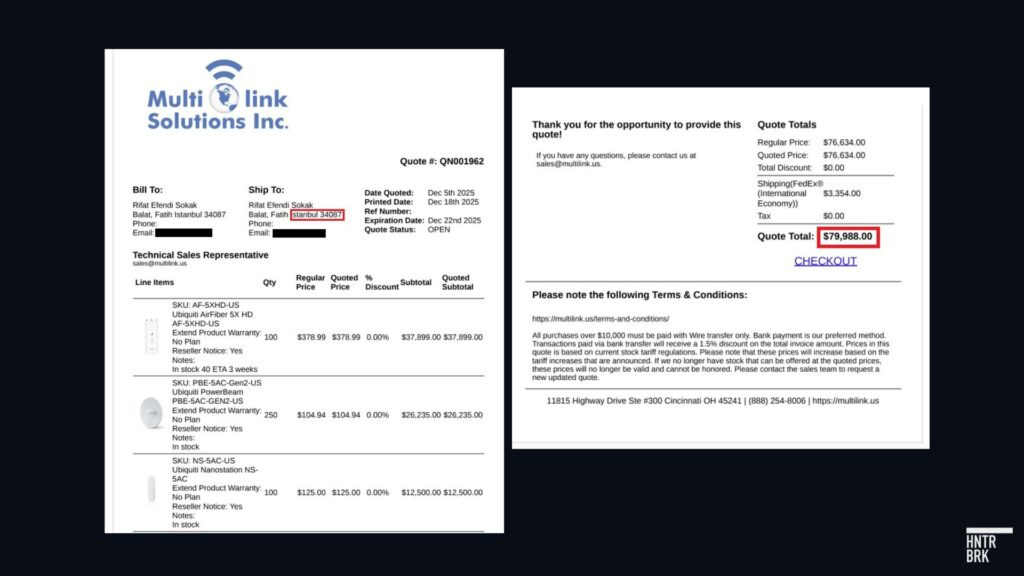

That practice — known as “transshipment” — struck close to home when a U.S. company, Multilink Solutions, agreed to ship 450 Ubiquiti devices after learning they were ultimately destined for Russia.

Initially, a Multilink representative said they could deliver the items directly to Russia.

Soon after, however, they followed up with a message that they couldn’t ship Ubiquiti devices to Russia, after all.

But they were able to work out a solution: a delivery address outside of Russia. After the reporter provided an address in Turkey, Multilink sent an invoice confirming the delivery was possible.

Multilink did not respond to Hunterbrook’s request for comment on these interactions, its compliance policies, and its relationship with Ubiquiti.

Routing products through intermediaries such as companies in third countries is a known diversion tactic, according to U.S. authorities.8

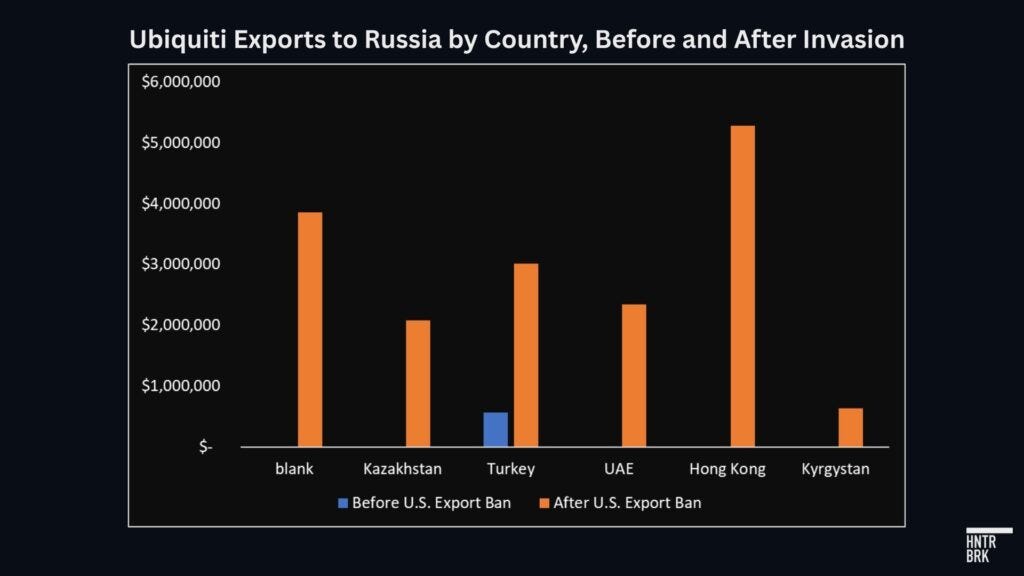

Yet, trade records suggest this is indeed how a lot of Ubiquiti products are ending up in Russia.9

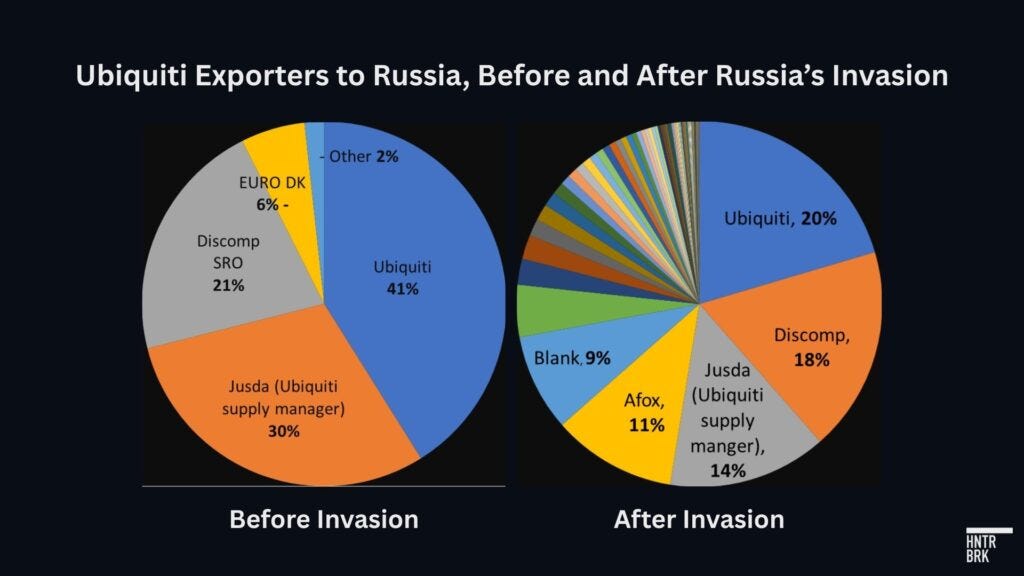

After Ubiquiti halted direct shipments to Russia following the invasion, Ubiquiti products continued to flow into the country from dozens of intermediaries, according to Hunterbrook’s analysis of trade data.10

In fact, the total value of Ubiquiti shipments to Russia surged 66% after the invasion, even accounting for any spike in shipments immediately before Russia’s invasion, possibly as distributors rushed their shipments to Russia in anticipation of export bans.11

And that number may not capture the true scale of the transfer of Ubiquiti products, as some companies falsify or omit identifying information like the country of origin, brand, and volume or value of the shipments to hide their tracks. For example, nearly $4 million of Ubiquiti shipments recorded after the U.S. export ban lacked the shipper’s name.

The items shipped include the latest models of Ubiquiti devices that were released for the first time after the ban, suggesting ongoing access to Ubiquiti’s central warehouses by these networks.

Among the exporters that supplied Russia with Ubiquiti goods after the invasion are about half a dozen official Ubiquiti distributors, with little apparent effort to obfuscate their activity.

Others appear to have halted direct shipments to Russia after the invasion but rerouted their shipments to Russia through intermediaries in third countries like Turkey and Kazakhstan, Hunterbrook’s review of trade data suggests.

Sometimes, their intermediaries were caught by Western governments for sanctions and export controls evasions, confirming their transshipment tactics. At least 10 intermediaries in countries like Turkey, the UAE, and China that were identified in the trade data as exporting Ubiquiti products to Russia have since been sanctioned by the U.S., Hunterbrook found.

Discomp: Distributor Playbook for Keeping Ubiquiti Flowing Into Russia

A closer look at Discomp S.R.O., a longstanding Ubiquiti distributor based in the Czech Republic, illustrates these tactics, according to Hunterbrook’s analysis of trade data.

Discomp shipped $1.8 million worth of Ubiquiti goods to Ivan Ionov Vladimirovich, a Russian client and owner of IT equipment wholesaler WiFiMag, for more than two years after Russia’s invasion — and after Discomp disclosed a notice from Ubiquiti warning its distributors against selling its products to Russia.

WiFiMag was an official Ubiquiti reseller as of 2014 and still claims to be one on its website. When contacted by a Hunterbrook reporter posing as a Russian military end user, a WiFiMag sales representative confirmed the availability of Ubiquiti equipment.

By mid-2023, Discomp appeared finally to have stopped its direct shipments to the Russian client. But it found another way.

Later that year, Discomp appears to have begun rerouting its shipments through a Turkish company called Olimpik Gama. Russian customs records show, however, that those shipments were destined for the same Russian client, with Olimpik Gama merely serving as a freight forwarder.12

The shipments stopped in March 2024, shortly after Olimpik Gama was sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department for evading sanctions. Discomp then began using another Turkish company, Unico Tekstil, to continue its shipments to Russia.

Discomp’s apparent routing of shipments destined for its Russian customer through Turkish entities contrasts sharply with its disclosures to Czech regulators. In its 2024 financial statement, the company wrote that it had “coped with the consequences of geopolitical events in Russia and Ukraine” by managing to replace the losses in those markets with customers in other markets.

Discomp did not respond to Hunterbrook’s request for comment as of the time of publication.

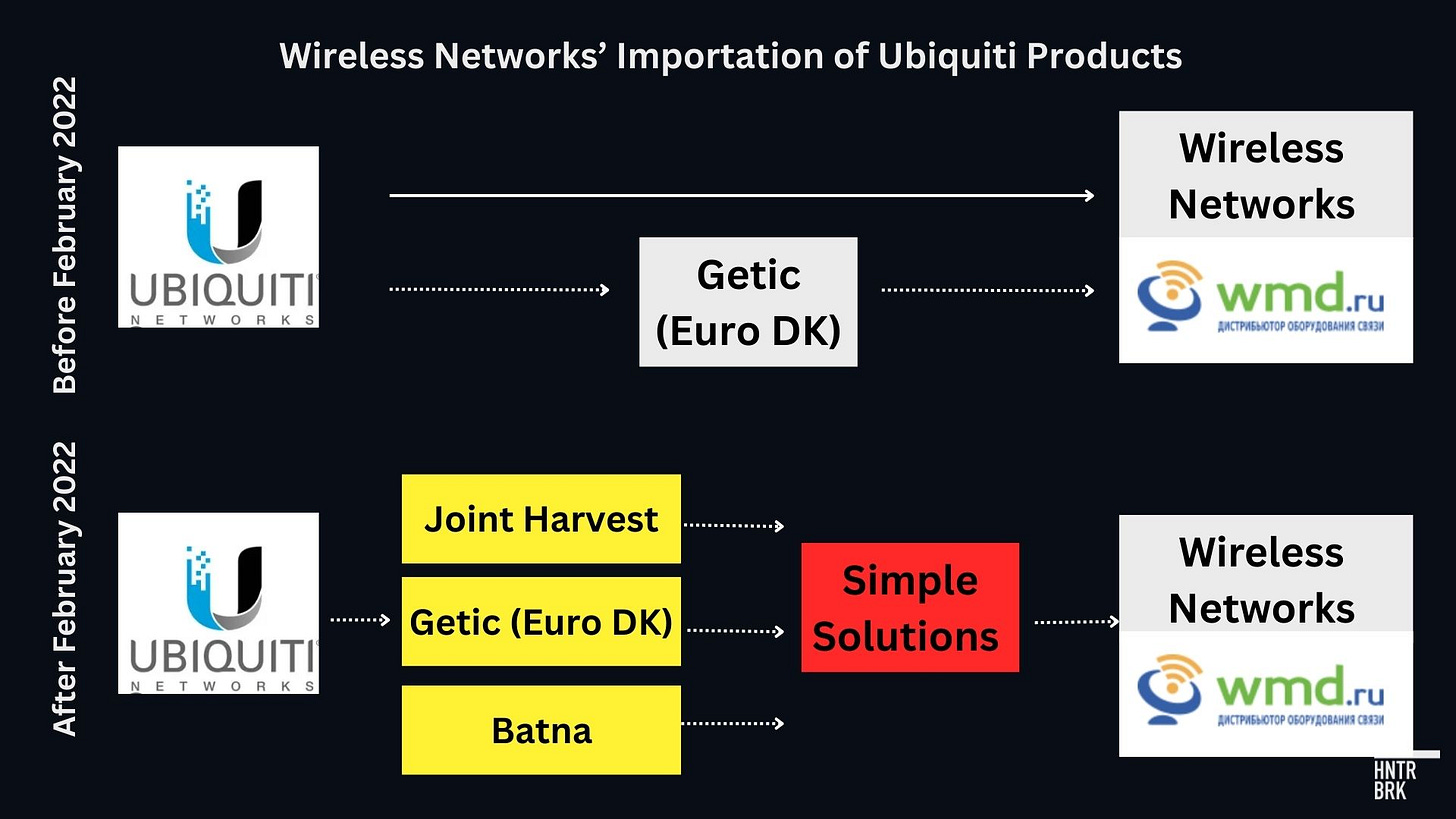

Simple Solutions, Kazakhstan: Another Window into Distributors’ Transshipment Tactics

A closer look at Simple Solutions, an obscure IT company in Kazakhstan, provides another glimpse into how re-exporters in third countries may be obtaining Ubiquiti equipment from official distributors to supply the Russian market after the export ban.

Multiple clues point to Simple Solutions being a shell company with the sole job of facilitating transshipments to Russia.

Simple Solutions was founded on March 11, 2022, according to Kazakh corporate intelligence site kompra.kz, in a small town in northwest Kazakhstan 80 miles from the Russian border. Hunterbrook couldn’t find an active website or online customer-facing presence associated with Simple Solutions that would suggest a commercial operation in Kazakhstan; the contact email listed in Kazakhstan’s business registry uses mail.ru, a Russian-owned email service. The company appears to be registered at the same address as Wireless Communications13, a Kazakh IT company that describes itself as an authorized Ubiquiti reseller, according to its Instagram page.

Shortly after its founding, Simple Solutions began importing Ubiquiti products from three official Ubiquiti distributors — Latvia-based Getic, Poland-based Batna, and China-based Joint Harvest, trade records show.

During the same period, 100% of Simple Solutions’ outward shipments went to a Russian IT company called Wireless Networks.

Wireless Networks owns an e-commerce site, WMD.ru, which was also once Ubiquiti’s official distributor. A WMD representative agreed to sell Ubiquiti equipment for military units fighting in Ukraine, telling Hunterbrook that their “resellers work with foundations and volunteer organizations” — a likely reference to volunteer groups that organize donation drives for the military.

Wireless Networks is also a supplier to ru-ubiquiti.com, another Russian Ubiquiti reseller that confirmed with Hunterbrook that it has provided Ubiquiti equipment to Russian military units, including a strategic missile force academy.

Before the invasion, Wireless Networks had received the majority of its Ubiquiti shipments directly from Ubiquiti, with Euro DK, Getic’s former name, making up the rest — or about 25%.

Unlike Discomp, however, Getic immediately halted direct sales to Russia in 2022, according to trade records. A Getic sales representative contacted by an undercover Hunterbrook reporter also flatly refused to sell to a Hunterbrook reporter posing as a Russian customer, explaining that “in accordance with existing restrictions, our products cannot be sold or transferred — either directly or through intermediaries — to the Russian Federation.”

In email responses to Hunterbrook’s request for comment, Getic CEO Igor Dekteryov said the company complies with “all legal and regulatory requirements applicable to our professional activities” with “the utmost care and diligence,” and that the company considers the military use of its products “unacceptable.” Dekteryov told Hunterbrook that it conducted due diligence on Simple Solutions and found nothing alarming.14

Batna responded to Hunterbrook’s request for comment, saying it complies with applicable sanctions regimes with “utmost diligence,” including by making their customers aware of the obligation to comply with export bans. Joint Harvest did not respond to Hunterbrook’s request for comments as of the time of publication.

Under EU sanctions law, EU-distributors like Getic and Discomp are not allowed to ship even to third countries like Turkey and Kazakhstan if they have reason to believe diversion is likely. In 2023, the EU passed a series of anti-circumvention mechanisms to hold EU companies legally liable for such exports that end up in Russia.

Simple Solutions’ new role in the Ubiquiti network is just one example. Trade records show, for example, just one Turkish exporter shipping a total of just $195,416 worth of Ubiquiti goods into Russia in the 26 months before the U.S. export ban. In the same time period after the ban, those numbers jumped to 18 Turkish exporters shipping about $3 million worth of Ubiquiti product — over a 1,000% increase.

Similarly, there are no records of the export of Ubiquiti goods from Kazakhstan, the UAE, Hong Kong, or Kyrgyzstan before the ban in the trade data Hunterbrook reviewed — those shipments appear for the first time only after the ban (see Case Study below for another example of how Ubiquiti distributors are rerouting shipments to Russia).

Ignorance Is No Excuse

The permissive nature of Ubiquiti’s distribution ecosystem is no accident. Ubiquiti’s reliance on third-party distributors is part of the lean cost model that’s been credited as key to its impressive margins — and which helped fund founder and CEO Robert Pera’s reported $377 million purchase of the Memphis Grizzlies in 2012, allowing him to become the youngest owner of an NBA team at the time.

It’s also a model that limits Ubiquiti’s control over its distribution. The company openly told its investors in its latest annual SEC filing, “We do not have any visibility on the location or extent of purchases of our products by individual network operators and service providers from our distributors.”

But that’s not a defensible excuse for violating export control and sanctions laws against providing sensitive goods to prohibited end users, legal experts told Hunterbrook.

“Ignorance is not really a practical excuse, or rather, a legal excuse, in most circumstances,” Richard Nephew, senior research scholar at Columbia University, told Hunterbrook. Nephew has served as the principal deputy coordinator for sanctions policy at the State Department.

That’s because U.S. export controls and sanctions regimes apply “strict liability,” Nephew explained, echoing other experts who also emphasized this point.

“Even if you have no knowledge that you’ve engaged in a violation … it’s still a violation,” Trevor Schmitt, a sanctions compliance lawyer at Arnold and Porter, told Hunterbrook. Strict liability is a legal principle that holds a party responsible even when there is no clear indication of negligence or intent to cause harm.

Even just having had a reason to know, or willfully avoiding knowledge, could be grounds to hold a company liable, experts explained. U.S. export laws define “knowledge” broadly to include even an awareness of a high probability and willful avoidance of knowledge.15

That definition may be difficult for a $34 billion global IT company to argue its way around.

How Much Does — Or Should — Ubiquiti Know?

Ubiquiti claims “we do not have any visibility” over the distribution network. But in a 2014 earnings call, the CEO admitted it was able to monitor its channels, specifically to Russia.

“We know that there’s a couple other guys that more than likely move some products into Russia,” CEO Robert Pera said, referring to Ubiquiti’s distributors. Ubiquiti hasn’t held an earnings call since 2018.

And a company like Ubiquiti could have the technical means to trace its products appearing inside Russia — possibly even back to the specific distributors or resellers involved — according to three industry experts Hunterbrook interviewed.

As of September 2025, Ubiquiti appeared to have placed an IP-based ban on firmware updates, based on complaints on a Russian user forum, suggesting Ubiquiti is able to identify a product’s location and deny service if the product user seeks an update.16

IP-based blocking is an inexact science and unreliable as an enforcement tool, experts told Hunterbrook. Russian users posted messages on the forum identifying simple workarounds like using a VPN to mask their location when connecting to Ubiquiti’s servers.

But IP-based detection is possible, and virtually impossible for a company like Ubiquiti to miss, industry experts told Hunterbrook.17

Large companies monitor IP flows on their cloud backends and can identify when something happens in a restricted region, especially if the users don’t turn on a VPN, Jim Salter, a veteran network-infrastructure analyst and an IT magazine contributor, told Hunterbrook. “Yeah, that’s instantly going to light up,” he said. “It’s going to look like a flare going off.”

And even when a user is trying to mask it, companies have ways to approximate the true location, according to the CEO of a U.S. smart-home integration firm that extensively deploys Ubiquiti products.

“If they chose to go digging, you can usually see, hop-to-hop-to-hop, this isn’t really in London — this is probably originating closer to Russia,” the CEO said.

Ubiquiti could even identify the specific hardware pinging Ubiquiti’s servers and trace it back to the original shipper. “From the serial number or the MAC address, you’d be able to see what unit that is and who it was originally sold to,” Lennert Buytenhek, a Lithuania-based networking engineer and author, told Hunterbrook.

But instead of prodding its distributors, applying its channel analytics for compliance, and exercising its technical controls to identify prohibited end users in Russia, Ubiquiti seems to have looked the other way.

In a post criticizing Ubiquiti’s alleged “doing business in Russia” on its online user community, an administrator shut down the discussion with a line:

“Your post violates community guidelines.18”

Ubiquiti’s Famed Efficiency: At the Expense of Compliance, Lives Lost

If a company could, should, or does know of potential diversions, what should it do to take responsibility and demonstrate compliance?

Hunterbrook asked 10 legal and sanctions experts.

The expectation isn’t for a company to prevent every violation along its supply chain, but rather for it to demonstrate that it took reasonable measures to prevent such violations, experts told Hunterbrook. Companies “can’t possibly know where every one of their devices ends up,” Doug Jacobson, trade attorney and an associate professor at American University, told Hunterbrook.

That doesn’t mean companies are off the hook. “There is an affirmative obligation for the company to conduct due diligence on end users,” Schmitt told Hunterbrook.

Similarly, Nephew said: ”The U.S. has set a pretty high bar on you have to know your customer.”

While there are no hard and fast rules on what those due diligence standards and processes must look like, experts offered concrete examples of typical measures that regulators expect from large companies involved in high-risk areas, such as using AI-enhanced screening software for anything Russia related; requiring distributors to submit end-user statements; and conducting field visits to countries like Turkey.

Detailed guidance from the U.S. Treasury Department on effective sanctions compliance includes conducting due diligence on customers, the supply chain, and any intermediaries through a compliance team led by a dedicated compliance officer; written policies and procedures; routine training; and auditing.

An effective compliance system should detect — as Hunterbrook did — when distributors openly export prohibited products directly to Russia or through identifiable transshipment routes.

“The conclusion is,” Schmitt told Hunterbrook, “that you, doing very little effort, were able to determine that it’s available for purchase by the Russian armed forces. … The company’s compliance team should be taking additional steps to prevent that, and should be identifying distributors that are the bad actors here.”

It’s unclear if Ubiquiti has implemented any of these practices. Ubiquiti did not respond to multiple Hunterbrook requests for comment on detailed questions regarding its compliance practices.

Ubiquiti’s Questionable Compliance Culture

Ubiquiti says it’s committed to compliance. But none of the policy documents Hunterbrook found — not the company’s Code of Business Conduct, a 2022 warning to a distributor, a 2019 information sheet, “U.S. Export Controls on Ubiquiti Products,” or a 2015 guide to U.S. export controls — described concrete mechanisms to enforce that commitment.19

A former Ubiquiti employee who oversaw product distribution provided a concerning glimpse of the company’s compliance culture.

The source, requesting anonymity to protect his professional reputation, described the company’s compliance department as a one-man shop, without an automated system to monitor compliance and identify red flags.

“All those processes that you would see at a large scale business don’t really solve the problem,” the source said. “The CEO of Ubiquiti recognizes that and just doesn’t care about all of the extra garbage.”

Ubiquiti’s operating structure seems to reflect a lack of emphasis on compliance. With just 1,667 total employees, 71% of the workforce is dedicated to R&D, leaving just 480 employees to staff all other departments running Ubiquiti’s global sales and operations, including compliance. That’s for overseeing $2.6 billion annual sales and nearly 600 distributors and resellers worldwide.

Fast-Forward, Repeat: Ubiquiti’s Ongoing Compliance Problems Globally

Ubiquiti’s lean, R&D-focused model had no compliance program, U.S. authorities announced in 2014, leading to prohibited Ubiquiti equipment worth at least $589,000 to be diverted to Iranian entities from 2008 to 2011.

U.S. authorities slapped a relatively modest $504,225 fine on Ubiquiti for the violations, taking into account the fact that the company had no history of violations and “took remedial action.”

“If violations should occur in the future, the response of regulators may be more severe in light of prior compliance concerns,” Ubiquiti told investors in their 2014 10-K filing.

“It can’t happen again,” the company’s CEO, Robert J. Pera, said in a 2011 Forbes article. “If it does, I’ll be in a lot of trouble.”

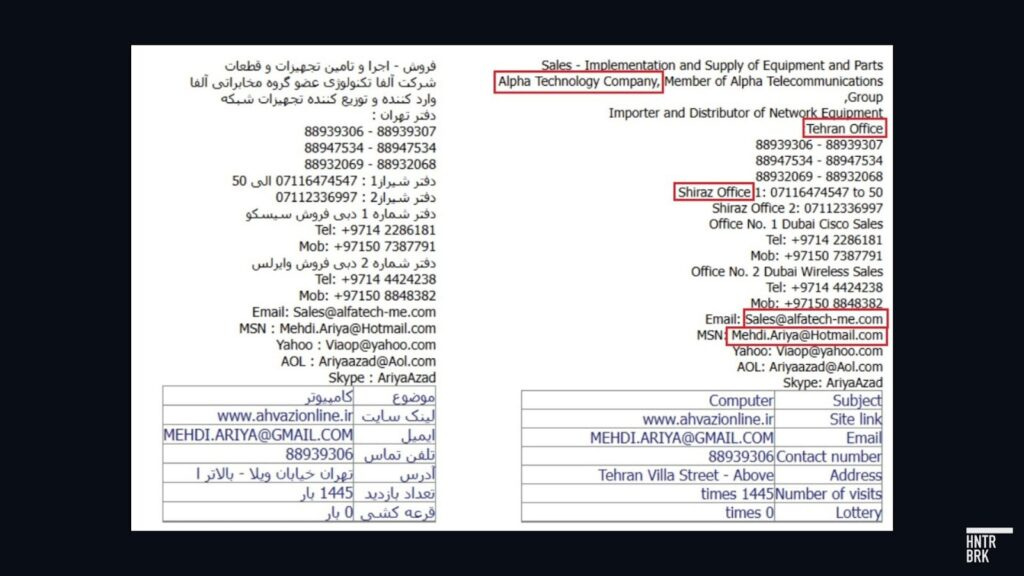

Over 10 years later, Ubiquiti’s compliance posture may not have improved much: Hunterbrook’s investigation suggests a Ubiquiti distributor may once again be supplying Iran.

UAE-based Alfa Tech, which Ubiquiti lists as an official distributor on its website, may be running branches in Iran, according to its Persian-language advertisements archived by Hunterbrook in May last year. The ads list Alfa Tech’s website and emails associated with Alfa Tech for contact, including the same email address associated with Alfa Tech’s domain name.

On Alfa Tech’s Telegram channel, which Hunterbrook archived in April last year, the first contact number listed is for the company’s Shiraz office, in Iran. The channel no longer contains references to an Iran branch. Alfa Tech did not respond to Hunterbrook’s request for confirmation whether the company maintains offices in Iran.

And Ubiquiti’s dealings with suspect partners don’t stop there, Hunterbrook found.

In South America, Osni Arruda, founder and president of Flytec Computers, a Paraguay-based Ubiquiti distributxor once responsible for 13% of Ubiquiti’s revenues, has been accused of smuggling, massive tax evasion, and money laundering in Brazil, and of involvement with the illegal housing of a large-scale bitcoin mining operation in Paraguay. Hunterbrook also found that, as of September 2025, Arruda also appears to own a building now occupied by IT distribution company Tecnotropolis, according to the Florida state corporate registry and Google Maps.20 Tecnotropolis has been accused of abetting a more than $1 billion money laundering operation tied to narcotrafficking, court records show.

And in Mexico, Ubiquiti distributor SYSCOM, which has a subsidiary that operates in the U.S. that is also an official Ubiquiti distributor, was quietly acquired by a Chinese state-owned IT company Hikvision in 2021, according to Hikvision’s annual report. That same year, the U.S. designated Hikvision as part of China’s military-industrial complex and banned the importing of communications equipment from Hikvision into the U.S.

The Cost of Noncompliance in Dollars … and Blood

The civil — and potentially criminal — liability a company faces for these types of compliance failures can be significant. The U.S. government warns that companies face administrative penalties including the “denial of export privileges, and placement of individuals and entities on lists that restrict or prohibit their involvement in export and reexport transactions,” as well as monetary penalties up to “twice the value of the transaction.”

Legal experts told Hunterbrook, however, that a criminal case usually requires evidence of the company’s explicit knowledge of diversion and willful violation.

That evidence may be hard to obtain without a formal government investigation with subpoena authority.

In the EU, enforcement can be uneven across jurisdictions, with some countries applying stricter definitions of EU laws to prosecute violations, Alex Prezanti, a UK-based lawyer specializing in international law and sanctions enforcement, told Hunterbrook. “Different member states have completely different standards for how they enforce EU legislation,” he said.

Beyond potential penalties for violating export controls and sanctions, Ubiquiti’s actions — or inactions — could expose the company to human-rights litigation in U.S. courts, according to Martin Flaherty, a law professor at Columbia University.

Flaherty raised the possibility of an Alien Tort Statute lawsuit in U.S. federal court by Ukrainian civilians who were harmed in Russian drone attacks. Such a case would rest on a theory that Ubiquiti — a U.S. corporation — aided and abetted Russian war crimes by providing connectivity for the Russian military to operate drones to kill civilians.

But the real cost of Ubiquiti’s compliance failures can’t be measured in regulatory fines or litigation damages. It’s the risk to Ukrainian lives — soldiers and civilians alike — killed in Russia’s brutal campaign in Ukraine, made possible in part by Ubiquiti technology.

Oleksandr Yasenchuk, an activist helping arm Ukraine’s defense, had a plea for the American tech giant: “I would ask them, if possible, to stop the sale of their technology to Russia.”

“They must understand,” he said, that the company’s money carries “the blood of Ukrainians.”

Oleksandra Ishchenko, a former Kherson resident, also urged Ubiquiti to just “look at all the materials” publicly available, to see “how much harm this brings, how many human lives it has taken.” Not doing so, she said, “equals supporting war and the murder of Ukrainians.”

“We are not stupid people, and we understand that this whole process is possibly not difficult for a large company to trace where their products are.”

“I think it’s a choice,” she added.

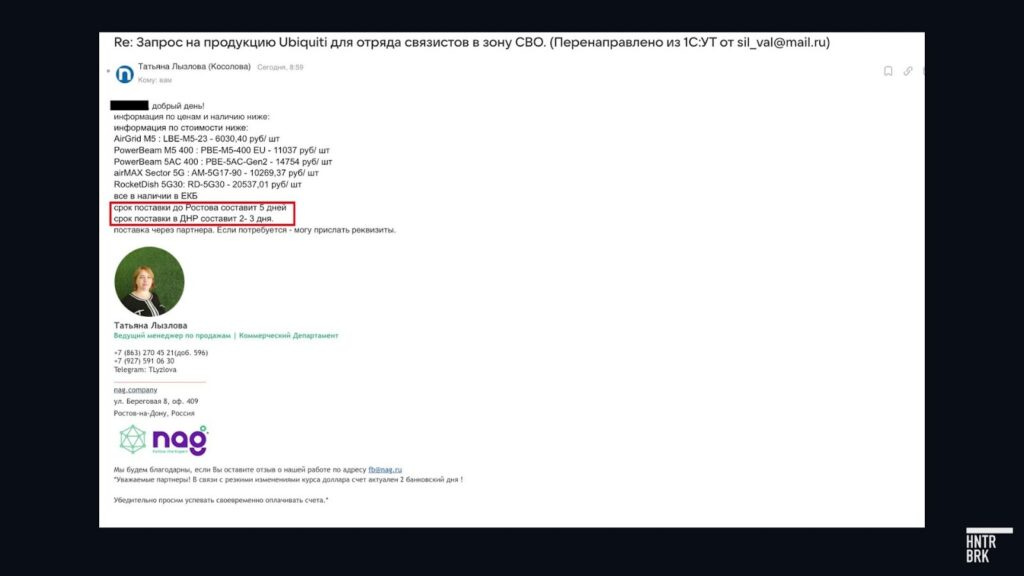

Appendix / Case Study: A Deep Dive into the Network Supplying Ubiquiti Goods to NAG, a Major Russian Distributor

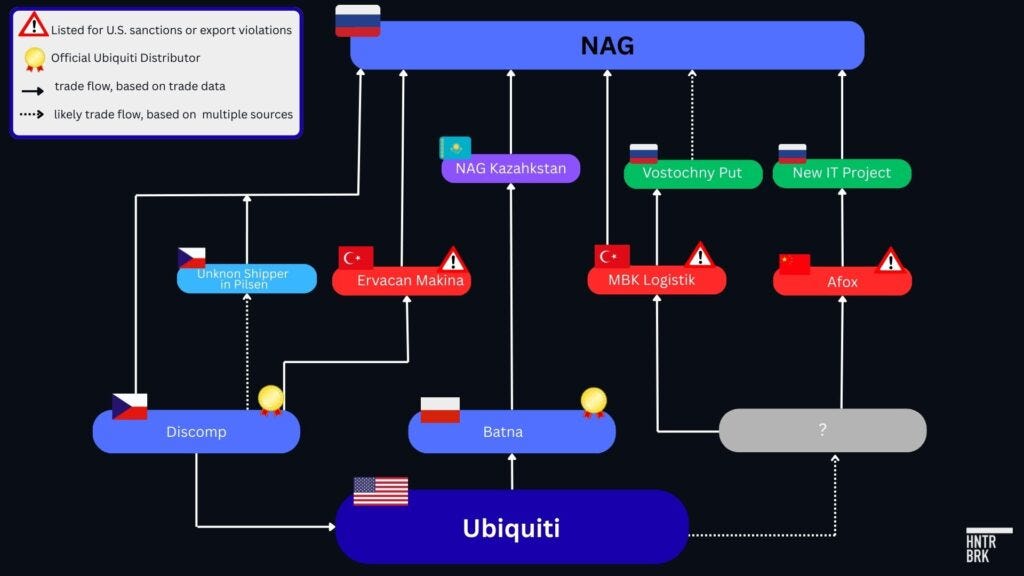

A deep dive into the import routes of one Russian IT equipment seller, NAG, helps show how the Russian market may be obtaining prohibited Ubiquiti goods through various trade routes that evade export controls and sanctions — and how Ubiquiti official distributors may be abetting those tactics.

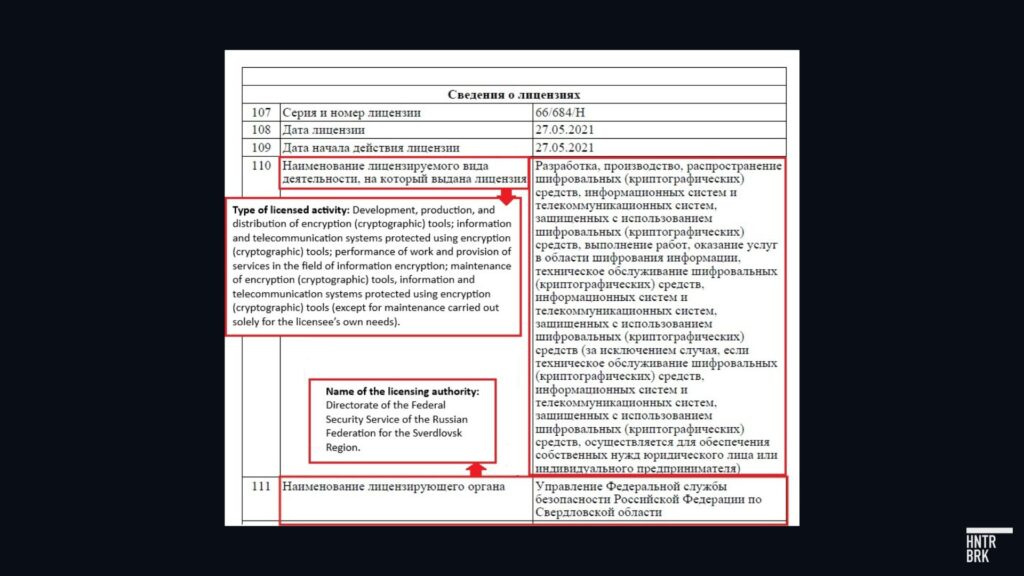

NAG was once Ubiquiti’s official distributor, according to the latter’s archived webpage. Among its government customers were PJSC Rostelecom and Russia’s Federal Security Service, according to clearspending.ru, an open-source portal for Russian government data. Rostelcom is Russia’s largest internet service provider and a state-owned company sanctioned by the U.S. The FSS, the U.S.-sanctioned successor to the KGB, is Russia’s main domestic intelligence service. NAG also holds a license with the FSS to develop and supply cryptographic equipment for the service, according to Russian corporate registry records retrieved from the Federal Tax Service of Russia.

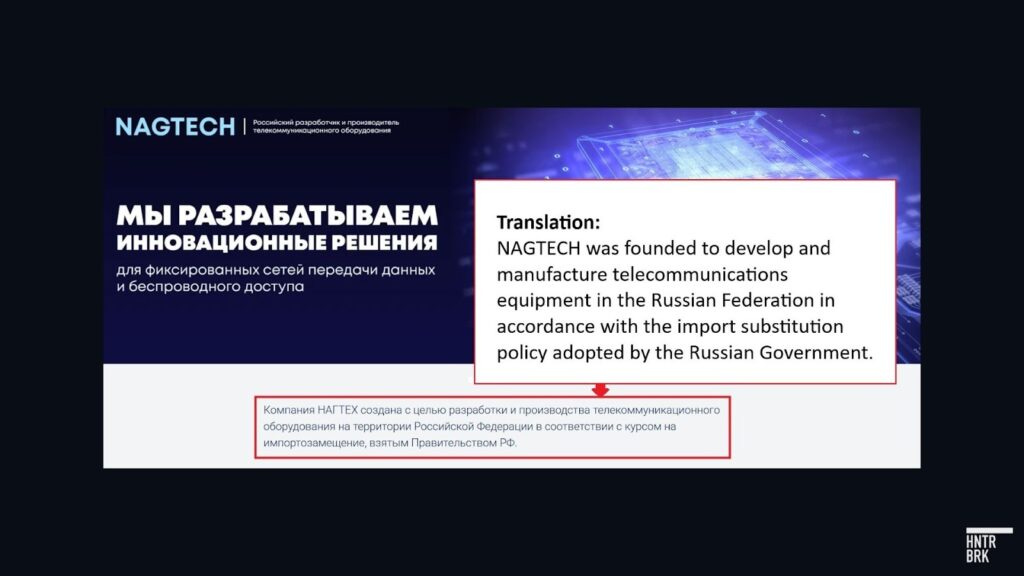

NAG also owns a 49% stake in a company called Nagtech, which was founded in 2021 expressly to support the Russian government’s policy of import substitution for key telecommunications equipment, according to its own website.

When contacted by a Hunterbrook reporter posing as a Russian customer seeking to purchase Ubiquiti devices for the Russian military in the occupied territories in November 2022, NAG confirmed that the items were in stock and promised to deliver them via local postal services. According to U.S. export control laws, the requested items are prohibited from export to Russia.

Hunterbrook’s analysis of trade records suggests that Discomp, NAG’s historic supplier of Ubiquiti goods, may have continued to supply NAG after the invasion, but obscured the shipment routes by removing its name from customs declarations or using intermediaries in third countries.

In the year prior to February 2022, NAG imported all of its Ubiquiti products from Discomp, valued at nearly $1.8 million, Russian customs records show. From February 2022 to April 2023, NAG imported nearly $4 million worth of Ubiquiti products, but the supplier’s name was removed from the shipment records. On some of the records, however, the location of loading was marked as Pilsen — a city in the Czech Republic where Discomp is headquartered.

Discomp may also have used a Turkish intermediary to continue supplying NAG.

From July 2022 to April 2023, Discomp exported about $2.2 million worth of Ubiquiti products to a Turkish locomotive parts company called Ervacan Makina; Ervacan was added to the Commerce Department’s Entity List in February 2024 for violating U.S. export controls on Russia. Discomp also shipped at least $1.9 million worth of Ubiquiti goods to Ervacan through a Lithuanian logistics company called Customs Warehouse UAB Didneriai.21 In many of the shipment records, the destination country was marked as Russia rather than Turkey — another sign of Ervacan’s likely role as a freight forwarder.

During nearly the same period, Ervacan supplied NAG with $6.1 million worth of largely tech equipment and parts, suggesting an active pipeline between Ervacan and NAG, although none of the shipments were labeled specifically as “Ubiquiti” brand.

NAG also used its subsidiary based in Kazakhstan to receive shipments from another Ubiquiti official distributor based in Poland, Batna.22 After the invasion, Batna exported over $530,000 dollars worth of Ubiquiti goods to NAG Kazakhstan, according to Kazakhstan trade data. During the same time frame, records show NAG Kazakhstan was exporting $1.3 million worth of networking equipment back to NAG and Nagtech, though the items were not labeled by their brand.

NAG is affiliated with Russian IT equipment sellers that also relied on transshipment routes — until the intermediaries were caught.

Beginning in July 2023, a Turkish logistics company called MBK Lojistik shipped a total of $960,000 worth of Ubiquiti goods to two customers in Russia, customs records show: about $60,000 was to NAG, and the rest was to another Russian company called Vostochny Put, a NAG partner company incorporated in June 2023.23

That shipment route ended around February 2024, when MBK Lojistik was sanctioned by the U.S. for sanctions evasions. It’s unclear who was supplying MBK Lojistik with Ubiquiti products.

NAG is also partnered with the New IT Project LLC, owner of Russian IT distributor 3Logic Group, a New IT Project representative told an undercover Hunterbrook reporter. Trade data shows that after the 2022 invasion, New IT Project imported over $5 million worth of Ubiquiti goods from Hong Kong-based AFox Corporation — until AFox was designated by the U.S. for sanctions evasions in support of Russia’s military industrial base in August 2023. It’s unclear who AFox’s suppliers were.

Banta told Hunterbrook in an email that it complies with applicable sanctions regimes with “utmost diligence,” but did not respond to Hunterbrook’s specific questions on our findings regarding NAG. Discomp did not respond to Hunterbrook’s request for comments as of the time of publication.

Authors

Jenny Ahn joined Hunterbrook after serving many years as a senior analyst in the US government. She is a seasoned geopolitical expert with a particular focus on the Asia-Pacific and has diverse overseas experience. She has an M.A. in International Affairs from Yale and a B.S. in International Relations from Stanford. Jenny is based in Virginia.

Blake Spendley joined Hunterbrook from the Center for Naval Analyses (CNA), where he led investigations as a Research Specialist for the Marine Corps and US Navy. He built and owns the leading open-source intelligence (OSINT) account on X/Twitter, called @OSINTTechnical (over 1 million followers), which also distributes Hunterbrook Media reporting. His OSINT research has been published in Bloomberg, the Wall Street Journal, and The Economist, among other top business outlets. He has a BA in Political Science from USC.

Till Daldrup joined Hunterbrook from The Wall Street Journal, where he focused on open-source investigations and content verification. In 2023, he was part of a team of reporters who won a Gerald Loeb Award for an investigation that revealed how Russia is stealing grain from occupied parts of Ukraine. He has an M.A. in Journalism from New York University and a B.S. in Social Sciences from University of Cologne. He’s also an alum of the Cologne School of Journalism (Kölner Journalistenschule).

Andrew Ford is an investigative journalist who exposed systemic flaws and prompted reforms in healthcare, business, policing, and state government. His reporting was published by ProPublica, USA Today, The Arizona Republic, Asbury Park Press, and Florida Today. He holds a journalism bachelor’s from the University of Florida and is based in Phoenix, AZ.

Michelle Cera trained as a sociologist specializing in digital ethnography and pedagogy. She completed her PhD in Sociology at New York University, building on her Bachelor of Arts degree with Highest Honors from the University of California, Berkeley. She has also served as a Workshop Coordinator at NYU’s Anthropology and Sociology Departments, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and innovative research methodologies.

Editors

Jim Impoco is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek who returned the publication to print in 2014. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has a Master’s in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life.

Wendy Nardi joined Hunterbrook after working as a developmental and copy editor for academic publishers, government agencies, Fortune 500 companies, and international scholars. She has been a researcher and writer for documentary series and a regular contributor to The Boston Globe. Her other publications range from magazine features to fiction in literary journals. She has an MA in Philosophy from Columbia University and a BA in English from the University of Virginia.

Graphics

Dan DeLorenzo is a creative director with 25 years reporting news through visuals. Since first joining a newsroom graphics department in 2001, he has built teams at Bloomberg News, Bridgewater Associates, and the United Nations, and published groundbreaking visual journalism at The Wall Street Journal, Associated Press, The New York Times, and Business Insider. A passion for the craft has landed him at the helm of newsroom teams, on the ground in humanitarian emergencies, and at the epicenter of the world’s largest hedge fund. He runs DGFX Studio, a creative agency serving top organizations in media, finance, and civil society with data visualization, cartography, and strategic visual intelligence. He moonlights as a professional sailor working toward a USCG captain’s license and is a certified Pilates instructor.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please email ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work, or press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2026 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided “as is” without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.

In most instances, either Hunterbrook identified products seen in battlefield footage as Ubiquiti's through visible logos, or the primary source or experts posting the footage identified the equipment. In a few cases, we relied on careful visual analysis along with expert consultation. It is possible that some of the radio bridge antennae we or our sources believe to be Ubiquiti's are made by another manufacturer; Hunterbrook found one instance of Russian soldiers using what Hunterbrook identified as a TP-Link device. The social media posts we reviewed by Russian volunteer groups that collect donations for the military also request Mikrotik, TP-Link, and other consumer-brand routers but appear mainly to seek Ubiquiti bridge antennae for radio bridges.

Ukrainian forces target Russian communications assets. Among other points of visual identification, the drone footage shows mounting hardware Hunterbrook found distinctive to Ubiquiti. Hunterbrook Media geolocated the footage to the Church of Elijah the Prophet in the town of Sudzha, Kursk Oblast (51.201784, 35.261477). Sudzha was the scene of a Ukrainian incursion into Russian territory.

News outlet Hromadske reported that in 2025 alone, Russian drone attacks numbering an estimated 97,000 killed 130 people in the Kherson region and injured 1,195.[

The Ubiquiti items Hunterbrook requested are tagged with a U.S. Export Control Classification Number indicating a designation by the U.S. Department of Commerce as dual-use hardware with potential for military and surveillance use. According to Ubiquiti’s website, well over 80% of Ubiquiti’s commercial product catalog carries an ECCN tag.

On February 24, 2022, The Department of Commerce adopted a “policy of denial” on all license exception requests for products destined for the countries.

The scrub, however, apparently hasn’t been thorough enough. On Ubiquiti’s Chinese-hosted website, one Belarusian firm still appears. Netlab Telecom, which operates the domain ubiquiti.by, openly advertises an extensive catalog of Ubiquiti products — including multiple items that are explicitly prohibited for export to Belarus under U.S. law.

Ubiquiti appears to classify its official distributors into three tiers: distributors, master resellers, and resellers. A Ubiquiti reseller told Hunterbrook that actual differences among the three tiers are minor, with distributors, for example, allowed to stock a little more. The reseller said that all are authorized and directly partnered with Ubiquiti.[

Shipments to companies in countries like Turkey and Kazakhstan that are not party to Western-led global export control regimes, particularly if they did not receive exports before February 24, 2022, are among the red flags identified by U.S. authorities as raising diversion concerns

Public trade data reflects only what reporting jurisdictions release and is inherently incomplete, particularly in the Russian sanctions context, where incentives exist to mislabel, reroute, or conceal shipments. Accordingly, observed trade flows should be understood as a partial snapshot rather than a comprehensive record, and the absence of data does not imply the absence of activity. Our methodology accounts for these limits by focusing on persistent, cross-validated patterns across multiple sources rather than isolated transactions.

Shipments from Ubiquiti or its supply manager Jusda International, continued until late 2022 — well after the U.S. export ban in February that year, perhaps to fulfill existing orders.

For an accurate comparison, Hunterbrook considered two periods of equal lengths (777 days, or about 25.5 months, each) before and after the U.S. export ban: 1) From January 9, 2020 (the first available trade data), to February 23, 2022, and 2) from February 24, 2022, to April 10, 2024.

The Russian customs records described the exporter as “DISCOMP S.R.O. via OLIMPIK GAMA IC VE DIS TIC SAN LTD.” (Translated by Hunterbrook).

Not to be confused with Wireless Networks of Russia.

In a follow-up response to Hunterbrook’s request for comment, Getic CEO Igor Dekteryov explained that, at the time, Wireless Communications and Simple Solutions had different addresses, giving Getic no reason to suspect there were any connections between the two companies. Dekteryov also shared what they believed to be Simple Solutions’ website at the time, at www.sskz.ky. The website is currently down, but an archived version dated September 16, 2024 — the latest available — shows a rudimentary site with hardly any identifying information about the company or its operations.

5 C.F.R. § 772.1 (“Definitions of Terms,” Bureau of Industry and Security, Export Administration Regulations) reads: “Knowledge of a circumstance (the term may be a variant, such as ‘know,’ ‘reason to know,’ or ‘reason to believe’) includes not only positive knowledge that the circumstance exists or is substantially certain to occur, but also an awareness of a high probability of its existence or future occurrence. Such awareness is inferred from evidence of the conscious disregard of facts known to a person and is also inferred from a person’s willful avoidance of facts.”

Ubiquiti’s likely IP-based ban followed the U.S. expanded bans on Russia to include IT and software-related support in 2024.

Multiple experts told Hunterbrook that Ubiquiti devices do not contain GPS-based location hardware — unlike Starlink terminals — which makes it harder to remotely disable them in embargoed regions.

Ubiquiti’s online user community is a key component of the company’s lean business strategy that leverages direct communications with users to cut production and marketing costs.

The most concrete example of Ubiquiti’s compliance enforcement policy Hunterbrook found was in a 2018 letter warning its distributor based in Moldova that a violation of U.S. sanctions and export laws may lead to Ubiquiti’s termination of the business relationship, found on the Moldova public tender database.

This location appears to be Flytec’s former address as well, before it moved to a different location recently. Flytec’s 2024 annual disclosure to the Florida Department of State listed the 3043 NW 107 Ave. address (the same one on an amendment filed by Tecnopolis). On Flytec’s 2025 annual disclosure, the company listed a different address in the same city, suggesting the company relocated some time between 2024 and 2025.

The trade records show $2.6 million worth of shipments of Ubiquiti goods from Customs Warehouse UAB Didneriai in Lithuania to Ervacan Makina in Turkey. Records for $1.9 million worth of Ubiquiti goods contain the words “BY ORDER OF DISCOMP S.R.O.” in the exporter name field.

Kazakh corporate registry information shows NAG Kazakhstan is owned by the same person as NAG in Russia and lists the same website and email contact.